How January 6 inspired election disinformation around the world

By: Jiore Craig, Cécile Simmons and Rhea Bhatnagar

13 January 2023

This Dispatch is the first in a series marking the anniversary of the January 6th insurrection. This piece explores the global phenomenon of election disinformation and the factors which influence whether those attacking democracy will be successful.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Days after the second anniversary of pro-Trump supporters seeking to overturn Joe Biden’s election storming the US Capitol, new images of supporters of ex-president Jair Bolsonaro occupying the presidential palace in Brazil are a stark illustration of how election disinformation has spread beyond the US and threatens electoral integrity around the world.

January 6, 2021 marked a watershed moment, highlighting the threat of anti-democratic extremism facilitated by social media. While researchers had warned for years that social media platforms were a breeding ground for disinformation and extreme views, it took an event of this magnitude to force politicians and the public to recognize the danger. The 2022 US midterms yielded disappointing returns for many prominent election-denying candidates, leading some to suggest that election denialism was a declining force. Events in Brazil call that analysis into question, reviving debates about just how concerned we should be about election disinformation both in the US and abroad.

Between January 6, 2021 and January 2023, major global elections in France, Germany, Australia, Brazil and others, provided insight into how causes organizing around election denial are hedging their bets online when they do not have the electoral majorities needed to gain power – and how despite being well-resourced, they are met with mixed results.

ISD analyzed online activity around elections in Germany, France, Australia, and the US midterms and found three recurring themes related to election denial. First, social media product features are amplifying election disinformation and assisting the organizing efforts of those pushing the false claims. Next, election denial conspiracies consistently have a mutually beneficial relationship with conspiracies based in hate, white supremacy, racism, homophobia, xenophobia and sexism. Finally, the success of election denial efforts online is mixed. Evidence suggests that election denialism alone is not an effective tool to speak to voters’ top concerns and is only sometimes effective for mobilizing and radicalizing. This efficacy is boosted when election denial narratives are mixed with hate-based conspiracies, and is diminished in countries with central election authorities and strong accountability measures.

Social media assisted election denial

ISD’s election work consistently shows the mutually beneficial relationship between platform product features and election denial. Research by ISD and many others during the 2020 US election showed a clear relationship between platform recommendations to users and their exposure to conspiracies and election denialism. Despite this relationship being illustrated many times over, ISD analysts once again observed platform product features assisting or facilitating the spread of election denialism content in the 2022 US midterms. In some cases, global platform product features – such as the shift to short-form video content on major platforms, including YouTube’s “Shorts” or Instagram’s “Reels” – were rolled out so fast to keep up with competitors that they made it easy for bad actors to use new features to evade the platforms’ moderation systems. This rushed rollout – happening in the midst of the US midterm campaign – left swathes of election-denial content unchecked.

Major platforms allegedly invest the most resources into protecting English-speaking users. ISD analyzed the rhetoric and threats emanating from US election denying communities both at a national level and in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, monitoring consistently during 2022. We found that platforms including YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and TikTok repeatedly assisted bad actors pushing election disinformation during the midterms.

Over the course of the midterm campaign, platforms inconsistently applied their election policies, promoted false claims about election outcomes in recommended content to users, enabled mainstream recruitment into online extremist spaces, and helped to algorithmically curate and recommend abuse targeting women candidates. ISD’s research also found that high-profile election deniers saw little resistance in promoting election fraud disinformation or seeking support for their efforts. On Twitter, 2000 Mules director Dinesh D’Souza repeatedly used his profile to promote his film, which is full of misinformation, to his 2.6 million followers with no consequences. On Facebook, election-denying organizations like the Election Integrity Network (EIN), which sought to recruit election deniers to poll watch in some states, were allowed to run ads.

In countries outside of the US, the platforms play a similar role – even when the election denial content is a direct copy of efforts in the US. In the run-up to the 2021 German federal elections, ISD research highlighted how false claims about postal votes and election fraud narratives imported from the US circulated in far-right online communities across multiple social media platforms. AfD-affiliated groups and politicians used social media advertising to promote these claims – meaning platforms profited from the dissemination of these false claims.

Likewise, during the French presidential election, ISD’s research uncovered attempts to spread voter fraud narratives, in particular repurposing US-born narratives surrounding the company Dominion which was at the heart of election disinformation in the US in 2020. Online actors spread these narratives with the hashtag #Dominion, taking advantage of the way platforms curate content based on hashtags. While these claims had minimal uptake, they were given some mainstream visibility by the ambiguous rhetoric of candidates such as Eric Zemmour, who called on his supporters to “not allow the election to be stolen from them.” Similar narratives were also seeded in online spaces dedicated to Zemmour’s candidacy, as well as far-right communities.

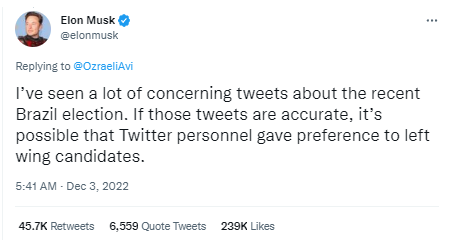

As so much control is in the hands of the small number of people controlling social media companies, we see individual actions at the top of major platforms impact election denial efforts. Since December 2022, ISD identified over 200,000 Twitter mentions of the English language hashtags #brazilianspring and #brazilwasstolen. Over 26,000 of these mentions were posted between 12-13 December 2022, when Brazil’s electoral court certified President Lula da Silva’s win. The most shared stories featured a New York Post article citing Twitter CEO Elon Musk’s claims that the platform distorted the Brazilian election in favor of the left under the influence of biased staff at the social media platform. Rest of the World reporting by Charlotte Peet shows how Musk’s takeover of Twitter (and the resulting gutting of Trust and Safety teams, and disbanding of the independent Trust and Safety Council) is correlated with a boost for right-wing election denying actors in Brazil on the platform. In November, Twitter also fired nearly its entire Trust and Safety team in Brazil.

Figure 1: A Tweet from CEO Elon Musk claiming Twitter personnel gave “preference to left wing candidates” during the 2022 Brazilian Presidential Election

Election denialism’s symbiotic relationship with wider hate and conspiracy

Election denial and those promoting it often leverage other hate- or fear-based conspiracies to seek their desired outcomes – and vice versa. Voter suppression targeting marginalized voters, xenophobia baked into campaign rhetoric and conspiracies, and explicit hate and threats of violence intimidating voters at the poll are well-established tactics used to underpin election disinformation’s believability. In recent years, the explosion of these tactics online has created new avenues for election denialism to benefit from hate and extremism. Likewise, actors steeped in hateful and extremist narratives have found ways to capitalize on election disinformation, allowing them to delegitimize democratic processes that do not deliver the outcomes they want, and further their exclusionary worldviews.

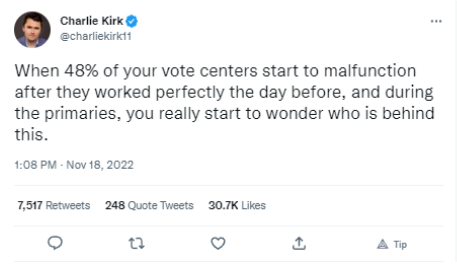

In the lead-up to January 6, 2021, through to today, research has highlighted how hateful actors in the US adopted election denialism for their cause to varying degrees. Charlie Kirk – Turning Point USA’s founder, who regularly uses anti-trans hate to build his audience on social media – was a key amplifier of election conspiracies in the lead-up to the election. Kirk posted Election Day conspiracies framing machine malfunctions and Democrat wins as outcomes manipulated by government officials on a near hourly basis.

Fig 2: A transphobic Telegram post by Kirk claiming social media is “the entry point for the contagion of Trans ideology”

Fig 3: A Tweet from Kirk alleging voter misconduct following the 2022 midterm elections

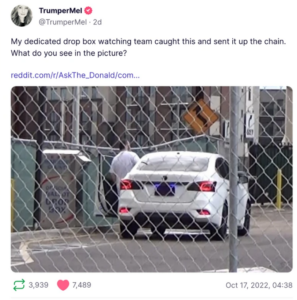

True the Vote (TTV)– an “election integrity” group known for pushing false claims of widespread voter fraud, including the debunked documentary 2000 Mules– colluded with prominent QAnon influencers to amplify varying election-related conspiracies. Melody Jennings– a QAnon conspiracy theorist and founder of “election integrity” group Clean Elections USA, who worked with TTV– regularly posted on fringe platforms asking her followers to “tailgate” drop boxes, and would attempt to “expose” individuals she believed were committing fraud. Though her initial efforts catered specifically to QAnon followers, her movement began gaining mass attention from notable figures, including Trump.

Fig 4: An organizing effort targeting QAnon supporters on Jennings’ Truth Social account

Fig 5: A Truth Social post by Jennings’ alleging voter fraud that gained mass attention across fringe and mainstream platforms, and was “re-Truthed” by Donald Trump

In Germany and France, election disinformation was easiest to find in extremist spaces dedicated to white supremacy or xenophobia, or conspiracy channels steeped in disinformation about the pandemic and government mandates. Ahead of the French presidential elections, the online communities most active in spreading disinformation were characterized by their opposition to vaccination and COVID-related restrictions, frequently promoting anti-elite conspiracy theories such as the “New World Order” and creating a climate of polarization and distrust in institutions in the run-up to the vote. In Germany, far-right groups seeded narratives intended to undermine the outcomes of democratic elections as far back as 2016. The 2022 federal elections in Australia saw the widespread circulation of conspiracy theories related to the World Economic Forum (“The Great Reset”), which had started to make inroads into Australian politics during the pandemic.

Election denialism sees mixed results

Election denialism has proven easy to find in most major global elections since January 6. Despite this ubiquity, however, denialists are not always able to achieve their aims. While this may not be the most click-bait worthy takeaway, it is arguably the most important. Media consistently overstate and misunderstand what makes election denialism online dangerous to democracy.

In cases where election denial narratives, whether originating at home or abroad, are adopted ahead of elections, efforts to propagate them to achieve offline outcomes see mixed results. ISD’s research highlights how Australian and French voters alike were targeted with disinformation claiming that Dominion voting machines– which had baselessly been tied to vote manipulation in the United States– would be used to rig the vote. Despite Australian law forbidding the use of voting machines altogether, and France having most votes cast with paper ballots, these claims still circulated in high volumes across social media platforms like Facebook and Telegram.

In contrast with the US, both France and Australia have elections administered by a central authority which is widely known to the public. Again, contrasting with the US, French presidential candidates showed restraint and largely denied election fraud narratives. In Germany, similar factors resulted in a failure of election denialists to gain substantial ground. Election disinformation was by and large limited to conspiratorial and fringe far-right, COVID-sceptic and pro-AfD communities. Several factors, including strong trust in mainstream media and Germany’s multi-party system being less prone to polarization, limited the reach of electoral fraud narratives.

In the United States, the decentralized approach to administering elections made the job of election denialists easy. In the lead-up to the midterms, they were able to openly run hyper-local disinformation and propaganda campaigns backed with huge resources. Even so, candidates in close battleground elections campaigning mostly on election denialism did not yield the results they wanted, with many losing their own races. However, the 2022 outcome by no means measures the repercussions election denialism has had in the US, or the possible effects on democratic processes in future instances. Specifically, in the months leading up to the election, ISD found that users in “election integrity” groups were being coached on voter intimidation laws, voting tactics to ensure votes count and how to report when they believe someone was engaging in fraudulent behavior. Additionally, analysts identified that followers were being urged to monitor drop-boxes as a means of protecting the integrity of the election, with a pointed emphasis on keeping a peaceful approach so the movement could maintain legitimacy. Despite consistent efforts and widespread reach to millions of people across the internet, these narratives were not persuasive enough to win majorities in key battleground races. Yet it did mobilize a percentage to take matters into their own hands, in what some have identified as voter intimidation, prompting disengagement.

Conclusion

Elections worldwide will always serve as a petri dish for bad actors across geographies to borrow from each other’s playbooks and right now, election denialism remains a popular play. However, it would be wrong to equate the pervasive existence of election denialism with a definitive statement that election denialism either is or is not the primary driver of electoral violence or democratic disruption. The real-world impact of electoral disinformation depends on the presence of conditions favoring its success. Social media product and policy lapses, along with the prevalence of hate and extremism, increase the likelihood election denialism will take hold. In contrast, strong central administration of elections, well-proven accountability mechanisms and the adherence of candidates to the norms of democracy make it much harder for denialists to win.

Digital policies in the EU and elsewhere may start to have an impact on these dynamics and offer another avenue for accountability. The following pieces in this series will examine each of these dynamics in more depth. As for upcoming elections around the world, election denialism will continue to rear its head. Close scrutiny is absolutely necessary to understand the specific dynamics of anti-democratic efforts, and to predict whether any given campaign of denialism is likely to transition into real-world impacts and offline violence. Until more effective accountability is in place, this outcome remains a concerning and realistic possibility.