Social media platforms and the drop box monitoring ecosystem

By Sabine Lawrence

7 November 2022

With Election Day for the midterm elections approaching and early voting underway, groups of ‘election integrity’ actors, election conspiracists, and extremists are organizing to obstruct a key facet of voter accessibility: ballot drop boxes. Drop boxes have been a talking point among right-wing and fringe groups since the 2020 election, with conspiracies surrounding ballot stuffing, ballot harvesting, and illegitimate votes linked to drop boxes remaining popular among election deniers. These groups have spent months recruiting individuals for vigilante action, stoking fears of untrustworthy election offices and previously “rigged” elections to frame drop box watching as a key force in protecting election integrity. Thousands of users are visiting drop box watching websites every month, with large portions immediately redirected to take action.

Efforts from ‘election integrity’ and conspiracy groups and organizations have led to concerns about voter intimidation and voter safety approaching the election, as vigilante filming and harassment from drop box watchers could dissuade early voters and endanger those who legally submit ballots for loved ones. As drop box monitors organize and share photos and film taken while monitoring, this content spreads to mainstream social media platforms including Twitter, Facebook, and TikTok, and is reframed with false and misleading claims that pose a threat to trust in elections. While Twitter has Civic Integrity policies to combat election disinformation, false content regularly remains unchallenged; meanwhile, Facebook and TikTok fail to place any concrete restrictions on content that could affect voters’ trust in elections.

Drop Box Monitoring Efforts

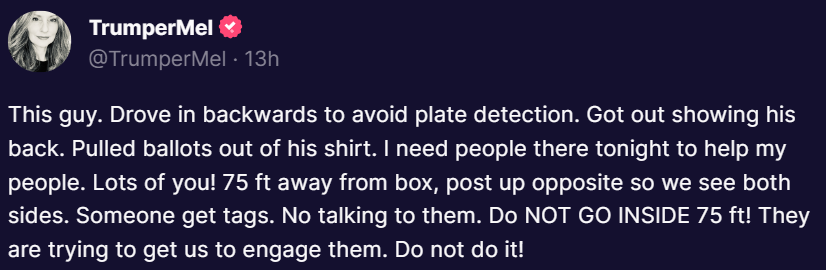

Drop box monitoring, also known as drop box watching or drop box “tailgating”, is when an individual or group sets up a spot near a drop box to observe voters depositing their ballots. Often individuals will attempt to capture photo and video of voters depositing ballots and share these with their peers via online platforms when they deem a voter to be acting suspiciously. When users post images of individuals or vehicles near drop boxes on Telegram, Truth Social, or Gab, commenters beneath those posts often encourage others to identify the person by recording the license plate/VIN numbers to store as monitoring data. Drop box watchers are also encouraged to submit their photos/video to designated email addresses provided by the organization, to keep a clear record of voters using drop boxes.

Drop box monitors and groups at times cite motivations linked to conspiracies from the 2020 elections, where they believe “ballot mules” illegally delivered thousands of ballots for Biden that should not have been counted. These conspiracies have remained consistently popular since the 2020 election, with pseudo-documentaries including 2,000 Mules adding fuel and legitimacy to these claims. In response to election conspiracies that often involve authority figures, both fringe and mainstream right-wing spaces express a loss of faith in the abilities of election offices and law enforcement to keep elections secure. These fears have since been transferred to the 2022 midterm elections, encouraging right-wing individuals who fear election integrity violations to turn to vigilante action.

While drop box monitoring groups often emphasize that participants should act lawfully (remaining over 75 ft away from the drop box, not engaging with voters, not bringing weapons), some counties are receiving reports of drop box watchers harassing voters and being armed. An incident in Arizona’s Maricopa County, with two drop box watchers wearing tactical gear with weapons, were reported to local police along with several reported instances of potential voter intimidation at drop boxes.

Additional concerns of confrontation stem from election conspiracies surrounding “ballot harvesting”. Arizona, Pennsylvania, and Michigan all have laws allowing individuals to submit ballots for other people, sometimes known as ballot collection. Examples of this legal practice include in Arizona (Statute 16-1005) and Michigan (Act 168.764a) which both restrict that right to household/family members, and in Pennsylvania (Act 320, Article XIII, Section 1306.1) where the law allows disabled voters to designate any voter to be their “agent” and deliver their ballot. For years, disinformation about unfounded “election fraud” has focused on this legal practice – framing it as “ballot harvesting” and right-wing propaganda doubled down on this frame after the 2020 elections. Now, regardless of specific state rules, drop box monitors are often expressing distrust of any individuals submitting more than one ballot, which could lead to harassment of voter submitting ballots legally.

Calls for drop box monitoring are present across the United States, but there are several notable efforts in Arizona, Pennsylvania, and Michigan. Online groups dedicated to drop box monitoring tend to have active social media accounts on Telegram, Gab, and Twitter and sometimes encourage members to contact and coordinate with sheriffs and sheriff organizations such as the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association (CSPOA). The actors involved in coordinating and encouraging these activities in three different states are outlined below.

Drop box monitoring efforts in Arizona are being driven by the Clean Elections USA Arizona Team, the former Oathkeepers affiliate group Yavapai County Preparedness Team (aka YCPT), “Oath Keepers of Yavapai County” and associated organization Lions of Liberty, and multiple Gab groups. These groups have sign-up lists for drop box monitoring shifts, lists of those willing to monitor, and a curated Google map of drop box locations. These groups request that drop box monitors to film voters but instruct volunteers to not approach or harass them. For example, YCPT encourages monitors to film “suspicious” people and note/record personal details (e.g., license plate numbers) to forward to their local sheriff.

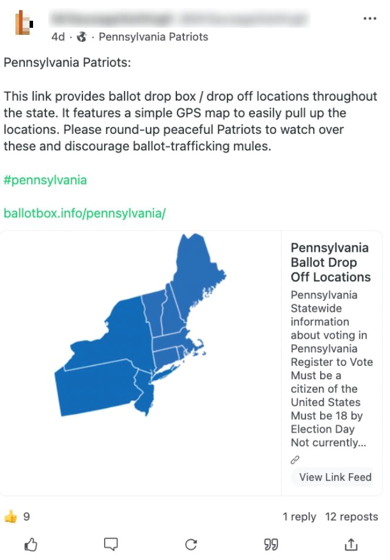

In Pennsylvania, this activity is being coordinated by “patriot” groups ChescoUnited and Audit the Vote PA, as well as Clean Elections USA. ChescoUnited created an “Election Watchers” web page that was shared on Gab that allows followers to sign up for different responsibilities, including drop box monitoring and “poll greeting”. According to this sign-up sheet, 69 of the 100 drop box shifts between October 25 and November 8 have been filled. Similarly, Audit the Vote PA plans to create signup sheets and fundraise for security cameras to install at drop box locations.

Figure 1: Pennsylvania Patriot group sharing drop box locations

The groups that are recruiting drop box monitors in Michigan are Michigan Citizens for Election Integrity (MC4EI) and former state senator Patrick Colbeck’s “Operation Overwatch” are recruiting drop box monitors. Operation Overwatch has ties to conspiracy theorist businessman Mike Lindell and the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association (CSPOA), a county supremacy organization. MC4EI is a prominent amplifier of election conspiracies online and leverages these narratives to recruit. Replies to calls for monitors are largely positive across platforms, with users frequently commenting that they signed up (though actual numbers of registrants remain unknown).

Site traffic data from Sept. 26 – Oct. 27 reveals variance in how drop box monitoring organizations from Arizona, Pennsylvania, and Michigan gain an audience. YCPT and MC4EI primarily get their site visitors from website referrals, Lions of Liberty and 100 Percent FED UP, respectively. By contrast, Clean Elections USA and Audit the Vote PA seem to use their site as a landing page for recruitment; 100% of site visitors leave the site to go to Zoom meeting or a sign-up sheet to get involved with supporting or participating in drop box monitoring. Each group’s website saw thousands of visitors in the past month, with Clean Elections USA seeing a consistent increase in traffic.

Figure 2: Clean Elections USA founder Melody Jennings encouraging drop box watching

Distribution of Drop Box Monitoring Content

Since drop box monitoring organizations usually have accounts on fringe social media platforms, including Telegram and Gab, photos/video/live posts tend to be shared both to the recommended submission email and to the platform account or channel. Users post updates on drop box monitoring, share images of themselves meeting other participants and of voters who use drop boxes, share right-wing media or news articles covering drop box watching, and call for additional volunteers. Posts and comments regularly use charged language, calling voters “ballot mules” and refer to voting via drop box as “trafficking” or “harvesting.”

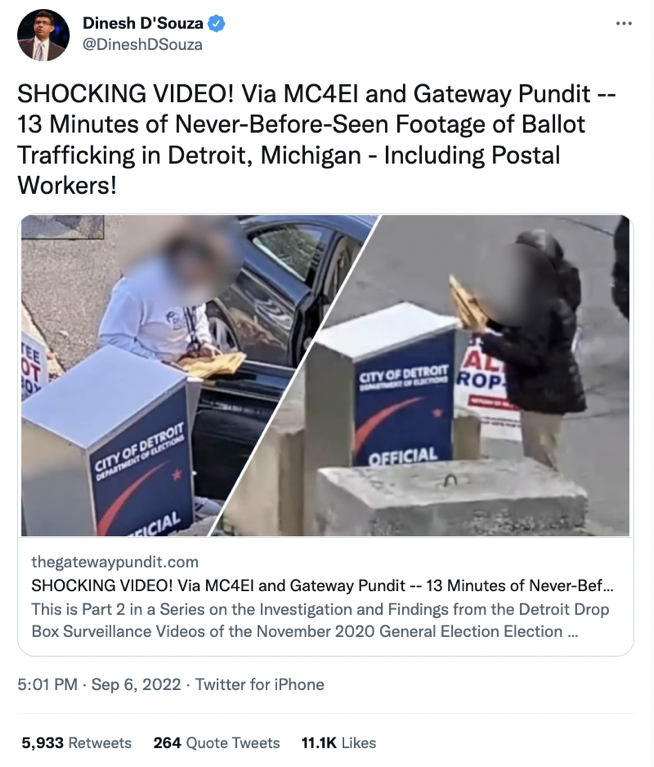

These posts then find their way on to mainstream platforms, including Twitter and Facebook, via screenshots and coverage from right-wing media outlets including Gateway Pundit and Breitbart. Screenshots often contain unclear images and/or text stating the image is evidence that “mules” are “trafficking” ballots. This creates a content pipeline from drop box monitoring groups (made up of election conspiracists, ‘election integrity’ groups, and extremists) to mainstream social media users and stokes uncertainty about the legitimacy of votes cast via drop box.

Drop Box Monitoring Content and Platform Policy

Other communications platforms used by these groups, such as Telegram and Gab, do not have specific policies on “election integrity”. A number of these platforms have also historically prized themselves on carrying out minimal moderate of the content they host in response to supposed “censorship” in mainstream spaces. In contrast, mainstream social media platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and TikTok, have listed “election integrity”’ policies intended to stem mis/disinformation campaigns. However, efforts from bad actors to sow distrust in legal methods of voting still reaches these platforms and remains largely unchecked.

Figure 3: Dinesh D’Souza sharing drop box watching footage

Twitter’s Civic Integrity Policy for Midterm Elections is the of the three platforms mentioned above, claiming they cover “misleading claims intended to undermine public confidence in an election” and intend to label and impede content that violates these terms. However, high engagement posts and posts from verified users that attempt to stoke distrust in election integrity remain on the platform without labels or restricted sharing, allowing these narratives to persist with more mainstream audiences. Posts from MC4EI drop box monitors showing individuals depositing multiple ballots, for example, spread among Michigan Telegram channels, gained coverage in a Gateway Pundit article, and then were shared by prominent Twitter influencers. These influencers included 2,000 Mules creator Dinesh D’Souza and Arizona Republican Josh Barnett, who collectively have over 2.7M followers. These tweets only displayed a prompt reminding the user to read the article before sharing, rather than an informational label about the midterm elections.

Facebook and TikTok, in contrast, have more nebulous and flexible policies. Facebook only states that they will “reduce” the spread of misinformation and will leave up come content that violates Community Standards in the name of “public interest”, indicating that content containing election disinformation does not explicitly contravene their election integrity policy. TikTok has a different but equally vague policy, focusing more on providing resources redirecting to verified election information rather than expressing commitment to hindering the spread of election conspiracy and disinformation.

All of these items constitute action by individual platforms, but as we’ve seen, it’s action largely without impact. While election deniers have posed a direct and growing risk to American democracy for more than two years, the response by platforms to address these dangers has been lacking and not proportional to the scale of the threat. As we approach the final days of the election, platforms have an opportunity to step up and do their part to prevent the evolution of election denial disinformation to in-person threats; a focus on drop boxes would be a good-faith sign that they’re taking election deniers seriously.