Five key takeaways from election denialist activity during the 2022 midterms

By Isabel Jones, Lucy Cooper, Sabine Lawrence, Rhea Bhatnagar, Eric Levai, Ciaran O’Connor, and Jared Holt

20 December 2022

Contrary to the anxieties of many, midterm election results have not provoked the same intense, eventually violent responses that unfurled after the elections in 2020. the last election ended in a deadly riot at the U.S. Capitol that resulted in the deaths of five people. A climate of political violence is alive and well in America while partisan activists have organized and acted on lies that any election their preferred candidates lose is an illegitimate election. The same communities that encouraged the conditions that produced the Capitol riot seemed poised to pounce at the democratic system again, this time backed by more resources and greater strategy.

Despite the best efforts of far-right Republican politicians, influencers, and media outlets that have primed their respective audiences with years’ worth of lies about the electoral process, that coalition of messengers ultimately failed to mobilize their followers to havoc. Many political newcomers who ran on election denial and loyalty to Trump lost their elections. With few exceptions they conceded to their opponents, rather than dispute their losses as many suspected they might.

Prior to Election Day, ISD analysts identified eight concerning trends observed among election denialist communities during 2022 primary elections, anticipating those trends would sustain as Election Day came and went. Though each trend analysts identified did in fact persist, none of them resulted in groundswells of real-world action, outside of a few key areas. There are many reasons chaos was less present in this election cycle, some of them inherent to non-presidential election cycles. For one, drastically fewer voters engage, let alone vote, during midterms.

ISD has monitored and analyzed the online rhetoric and activities of prominent election-denialist communities nationally and in five target states: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. What follows is a list of trends ISD analysts identified from their observations of those communities in the month before and after 2022 Election Day. ISD will continue its monitoring through the 2022 certification process and beyond. Though midterm elections did not devolve into the widespread turmoil many feared they could, the threat posed by political violence and anti-democracy movements remains as pervasive and pernicious today as before the midterms.

Election deniers’ messaging was severely undisciplined before, during, and after Election Day

For all the resourcing of election denialist groups and their media megaphones, and a fresh splurge of dollars into apps and information crowdsourcing tools, election deniers’ narratives were largely disjointed. Election deniers switched, rekindled, and abandoned narratives in the weeks before and after Election Day. Some things remained constant, namely that elections were illegitimate and that Democrats, election officials, and companies that make election infrastructure, like vote-counting machines, are to blame. It remains unclear what narrative shifts will persist into the 2024 election cycle at the time of writing.

Before Election Day

Several conspiracy theories blossomed in election denialist communities in the run-up to midterm elections, and many of them regurgitated or played upon preexisting narratives that achieved traction in 2020. Prominent national narratives included claims that early and absentee voting were untrustworthy methods of casting ballots, voting infrastructure and reporting methods were untrustworthy, voters could be offered pens at polling locations that would void ballots, and software used to store election worker data was linked to the Chinese government. Such claims were shoehorned into local contexts by myriad community and regional election denialist groups, who in turn used the narratives to guide their interactions with their relevant election offices.

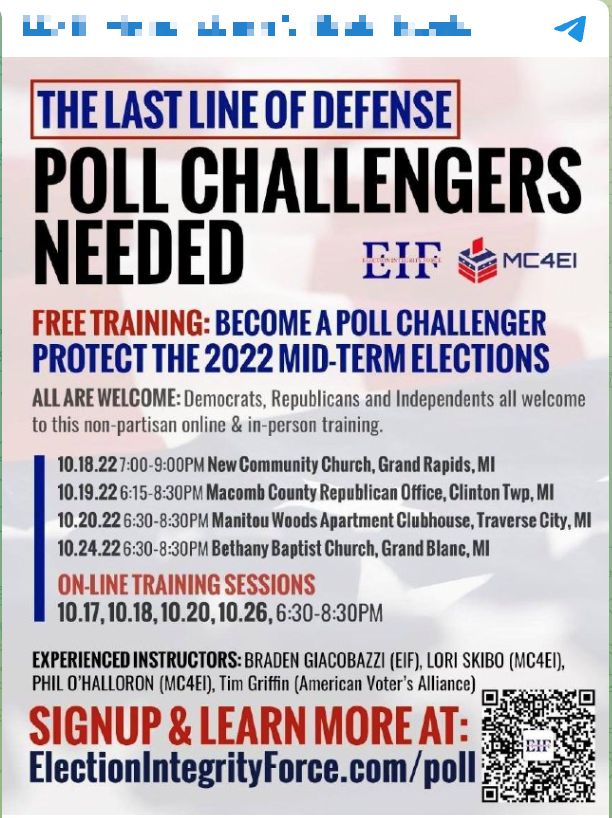

Clusters of election denialists encouraged by QAnon-supporting Truth Social influencer Melody Jennings to surveil and document activity around ballot drop boxes in Arizona, driven to action by faulty national narratives alleging drop boxes were used to facilitate voter fraud. Some of those individuals displayed firearms and wore tactical garb as they watched the boxes, and several voters filed complaints of voter intimidation. Conspiracy theorist influencers encouraged their followers to solicit state and local election offices for 2020 election data to be later compiled into databases, resulting in waves of submissions overwhelming many election offices. Some online groups encouraged election deniers to volunteer as poll workers with inflammatory language and claimed to have recruited hundreds or thousands of poll workers, though ISD cannot independently verify those claims.

Figure 1: A flyer shared by election denialist group Michigan Citizens for Election Integrity on Telegram calls poll challengers “the last line of defense.”

On Election Day

As voters cast ballots on Election Day, election-denialist influencers and outlets directed their followers’ attention to what were often genuine hiccups in the election process, including malfunctioning machines and long lines at polling locations. Unlike 2020, election denialists were able to link errors and unclear situations to dishonest narratives that frame such unknowns as proof of fraud, successfully seeded in their audiences over the preceding years.

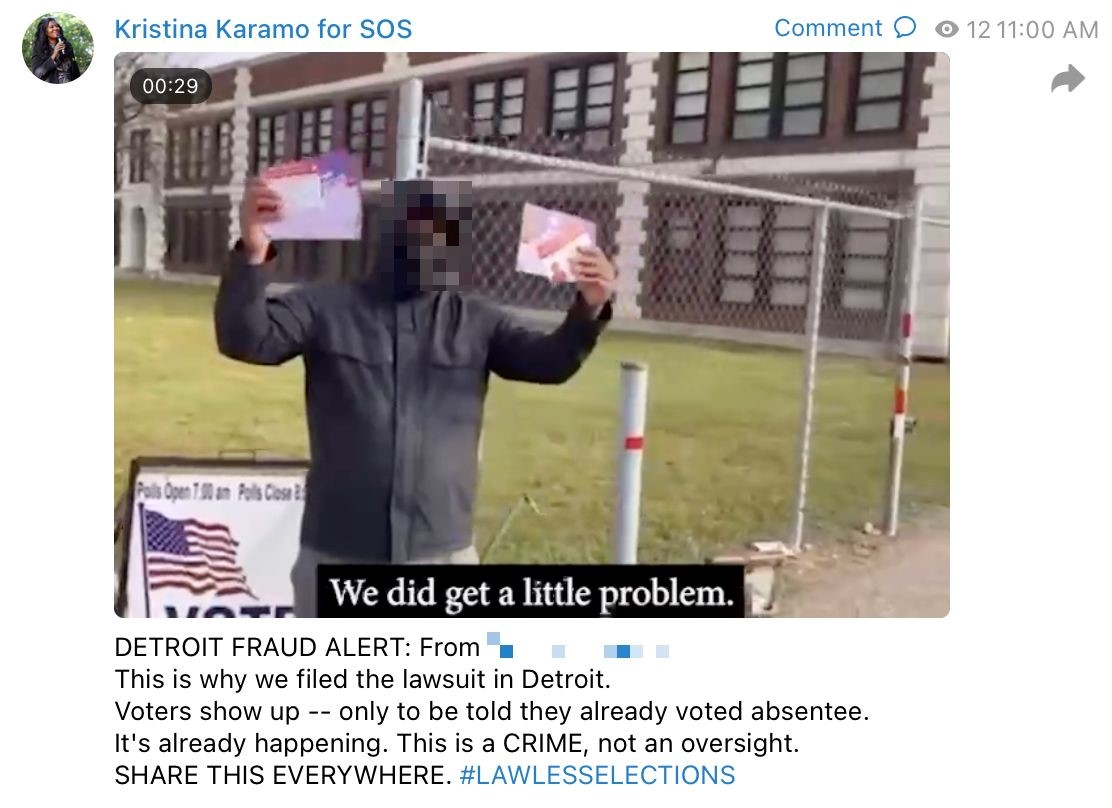

In Detroit, Michigan, an error with software used to check-in voters caused some voters to be incorrectly told they requested an absentee ballot. The technical problem was resolved and no one was prevented from voting, yet high-profile partisan figures hyped the software issue throughout the day, eventually leading Trump to call on his supporters to “Protest, Protest, Protest” in Detroit on his Truth Social account. Former Michigan secretary of state candidate Kristina Karamo called the incident a “CRIME” on her social media accounts.

Figure 2: Former Michigan secretary of state candidate Kristina Karamo tells her Telegram followers that polling place errors in Detroit were a “CRIME.”

Some Arizona voters shared footage and photographs of voting issues at Arizona polling locations in majority Republican districts on Twitter, Telegram, and other platforms on Election Day. Right-wing influencers and media outlets capitalized on voters’ concerns to lend faux-credibility to existing narratives alleging a Democrat-run conspiracy to suppress Republican votes. Former attorney general candidate Mark Finchem and former gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake were among those who spread such reports to advance faulty narratives alleging wrongdoing.

After Election Day

After Election Day results revealed that an anticipated “red wave” of Republican wins hadn’t come to fruition, and many election-denying candidates who lost conceded to their opponents, election-denialist influencers and media outlets scrambled for explanations.

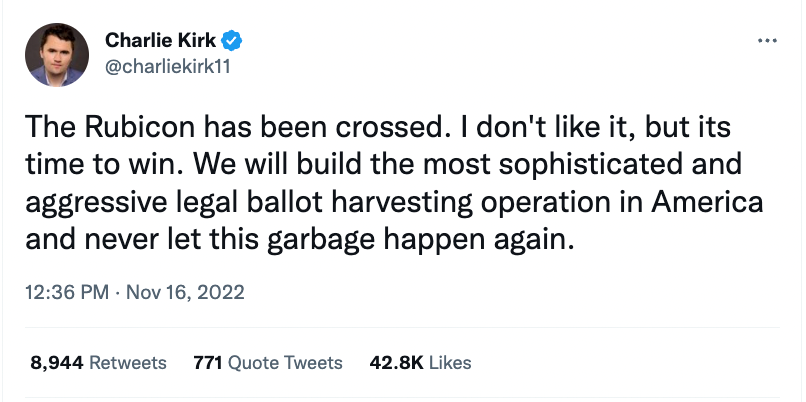

Turning Point USA leader Charlie Kirk, who was among the gaggle of national figures alleging mail-in ballots were vehicles for voter fraud, seemed to reverse course entirely. Kirk suggested that Republicans should build a “ballot harvesting operation” of their own—in other words, arguing that Republicans should undertake efforts to encourage their base to vote by mail. Elsewhere online, ISD analysts observed users in election denialist communities discussing whether ballot drop boxes, a years-long fixture of conspiracy theories about voting, should be installed in spaces perceived as conservative, like gun shows. It remains to be seen whether these apparent reversals will be sustained.

Figure 3: Turning Point USA leader Charlie Kirk writes on Twitter that Republican will create “the most sophisticated and aggressive legal ballot harvesting operation” in the US after losses in 2022 midterms.

Some groups of election denier activists apparently missed the pivot and predictably shifted their attention to the certifications of elections their preferred candidates lost. Despite disruptions and angry rhetoric at certification meetings, as observed in Arizona and Michigan, election results were certified. As results were certified, some members of election denialist communities have alleged that electoral and judicial systems may be too powerful for their movement to change or overpower, though consensus about what action could remedy that perceived issue was disjointed.

Lacking central leadership, many election-denying narratives failed to sustain

The potential for disruption driven by election misinformation after Election Day was high. However, in most states, losing candidates conceded their races soon after news outlets projected their losses. Comparing the post-election reactions of election denialists in places like Michigan, where high-profile election denialist candidates conceded, to those in Arizona, where similarly aligned candidates have disputed results, it would seem a lack of leader or contributed to denialist narratives’ staying power.

In Michigan, election deniers Tudor Dixon, Matt DePerno, and Kristina Karamo, ran for governor, attorney general, and secretary of state, respectively, on platforms that included election denialism. Each engaged with other election-denying figures, amplified misleading and false narratives about the 2020 election, and used their online presences to encourage distrust in the state’s election administration. All three lost their elections. Dixon and DePerno conceded on November 9. Karamo did not formally concede but she did announce her next political pursuit, effectively abandoning her 2022 efforts. These candidates chose not to contest Michigan elections, as did most activists in the state. Analysts observed almost no election-related protests after Election Day.

Conversely, Arizona Republican gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake played a significant role in keeping election denialism front and center in Arizona politics. After November 8, Lake pivoted from one baseless narrative to another, amplifying claims of partisan voters who supposedly faced obstructions in voting and attacking Governor-elect Katie Hobbs as illegitimate while denying her loss. Other election deniers, including Arizona Sen. Wendy Rogers and former Republican attorney general candidate Mark Finchem, put forward similar or identical claims to Lake’s, comprising a larger central network to espouse bogus claims about the state’s elections.

Figure 4: Former Arizona gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake appears on Steve Bannon’s “War Room” podcast on December 5, 2022.

Lake’s persistence was rewarded; no other midterm candidate received comparable coverage or post-election media opportunities. In the month after Election Day, ISD analysts counted eight appearances on Fox News, four on Steve Bannon’s podcast, and three on Charlie Kirk’s podcast. The Gateway Pundit, a hyper-partisan and conspiratorial blog, published 65 articles about Lake’s campaign in the same period. As a result, national election denialist communities have fixated on Arizona elections, encouraging and cheering delays of certifications in Cochise County and claims of voter suppression in Maricopa County.

In the absence of central leadership, some election-denialists engaged their own networks via self-titled “Patriot” groups: locally focused “election integrity” advocates that act on claims the 2020 and 2022 elections were rife with fraud. Such groups have made considerable efforts to sustain election fraud narratives and advocate against election certification, particularly in Pennsylvania where they created and filed more than 100 petitions for 2022 election recounts across multiple counties. Pennsylvania “Patriot” groups were active before the elections, recruiting poll workers, organizing surveillance of ballot drop boxes, and mobilizing supporters to protest mail-in voting outside of county officials’ offices. Following midterm elections, Pennsylvania group leaders expressed intent to increase coordination between groups and suggested their efforts will continue into 2024.

Figure 5: A Telegram user reacts to news of former Pennsylvania gubernatorial candidate Doug Mastriano’s concession to Governor-elect Josh Shapiro with angry rhetoric.

Far-right communities didn’t overcome fears around election-related protesting

While online conversation among election deniers indicated a desire among communities to see large rallies and protests after Election Day losses, few materialized. Small rallies with fewer than a dozen people occurred but were rarely disruptive; many events ISD analysts learned of from observing election denialist communities failed to even make their local news. Additionally, the bulk of violent extremist movements did not engage with 2022 election organizing in a way remotely comparable with post-election organizing in 2020.

Instead, local protests against generalized targets, like LGBTQ+ communities, regularly drew more engagement and attention than election-related ones, even during the period surrounding Election Day. Researchers at the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) have noted a sharp increase in anti-LGBTQ+ mobilization in the United States in 2022, nearly tripling since 2021. ACLED also observed the trend held with engagement from far-right movements; militias and militant social movements appeared at more than triple the number of anti-LGBTQ+ events as in 2021. Though many election-denying candidates attempted to capitalize on existing anti-LGBT+ rhetoric and organizing, they largely proved unsuccessful at translating into election-related protests.

Some struggles would-be organizers faced can be attributed to the sprawling nature of online conversation, which can conflict with regional organizing. National election denialist influencers who direct online attention to a state election may not accurately represent the efforts or interests of local on-the-ground organizers. Likewise, members of state-focused communities who do not actually reside in their target states face significantly higher burdens when attempting to organize offline actions. This dynamic is less disruptive during presidential election years, when voters share the same choice at the top of their ballots.

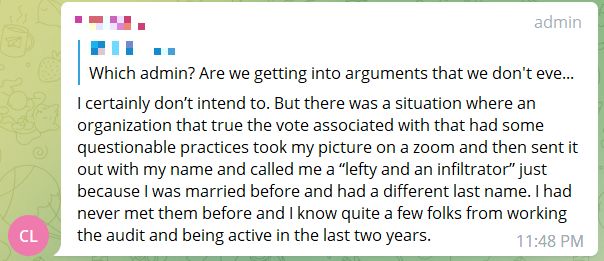

Many election-denying communities were vocally afraid of legal trouble in wake of the widely publicized arrests of more than 900 people who engaged in the January 6 Capitol riot and announcements from the Department of Homeland Security identifying election denialism as a possible driver of violence. As was observed in far-right movements’ prior attempts at centrally organized protest movements since the Capitol riot, election-denying groups with otherwise similar intentions were observed infighting and accusing would-be protest organizers of working with law enforcement to entrap Trump supporters. On more than one occasion, ISD observed groups accusing each other of infiltration or spying.

Figure 6: A Telegram user complains of being labeled a “lefty and an infiltrator” by an election denialist group despite “being active” in election denialists’ activities “the last two years.”

Fear of law enforcement infiltration or corruption has also clashed with the generally favorable opinion reactionary right movements have of law enforcement, contributing to organizational paralysis. Some election-denying groups sought to forge relationships with so-called “Constitutional Sheriffs” they thought would be supportive of their efforts, but it was not enough to overpower many election deniers’ simultaneous belief that police are complicit in supposed vote fraud and seek to punish those who speak out against it.

Tech platforms allowed high-profile influencers to spread bogus narratives without apparent intervention

Mainstream Platforms

Mainstream Platforms

False and misleading claims about election fraud received significant traction on both mainstream and fringe platforms. Days before midterm elections, ISD published an article exploring how election disinformation was thriving in social media platforms’ prioritization of short-form video content. A review of the same research more than a month later found that although some hashtags were no longer available, short-form video platforms still hosted gobs of election-related conspiracy theory content. Analysts even found one TikTok user who posted the entirety of Dinesh D’Souza’s conspiracy film “2000 Mules” on the platform.

Figure 7: A user uploads the “2000 Mules” conspiracy film in nine different seven-minute segments to TikTok.

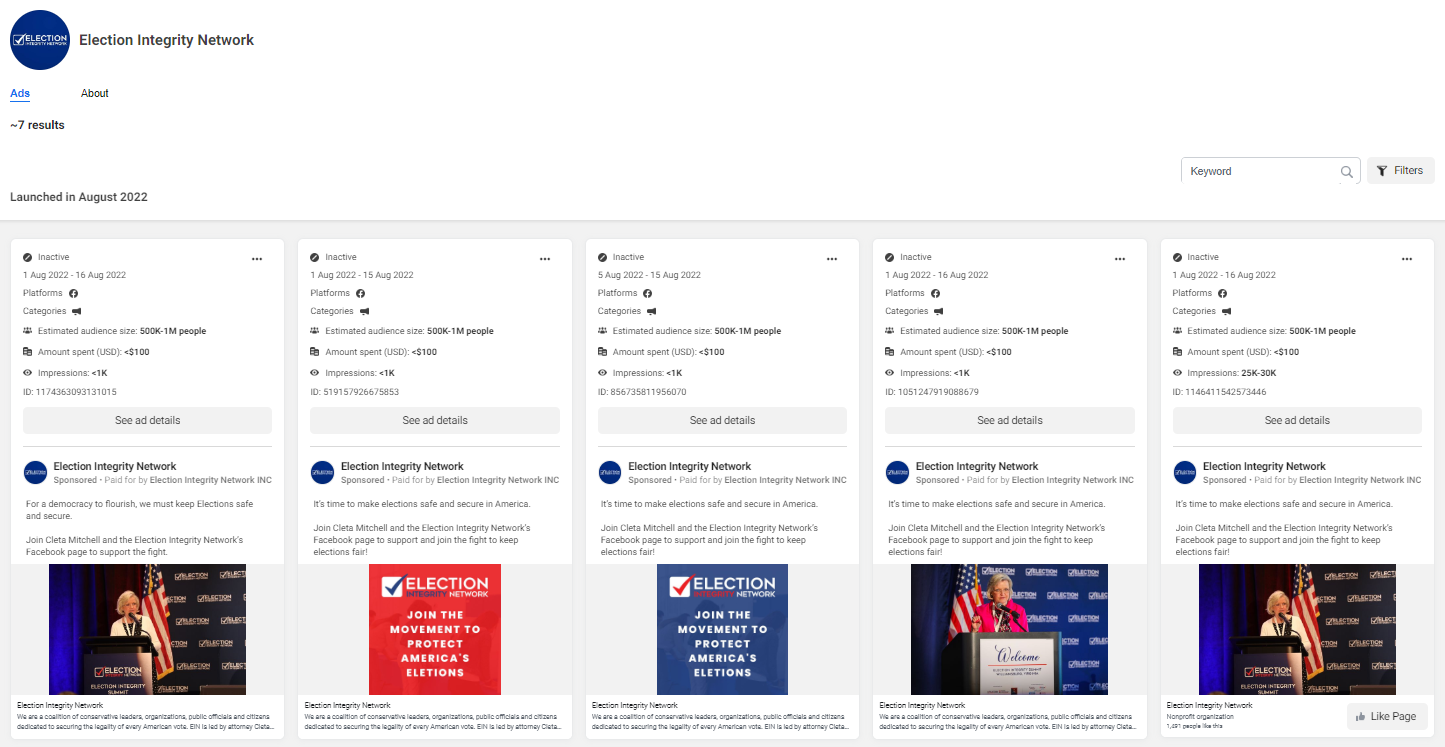

On other major platforms, high-profile election deniers saw little resistance in promoting election fraud disinformation or seeking support for their efforts. On Twitter, 2000 Mules director D’Souza repeatedly used his profile to promote his film to his 2.6 million followers with no consequences. On Facebook, election-denying organisations like the Election Integrity Network (EIN), which sought to recruit election deniers to poll watch in some states, were allowed to run ads. were observed. Turning Point USA leader Kirk and hosts of influencers affiliated with his organization boosted misleading information about the 2022 vote to a collective millions of Twitter followers with no apparent interventions.

Figure 8: Election Integrity Network runs Facebook ads prior to midterm elections.

Even figures banned from mainstream platforms saw their messages disseminated on those same platforms. In Trump’s announcement of his 2024 presidential candidacy, the former president suggested without evidence that China interfered to help President Biden win the 2020 election. Though both Trump and election misinformation are against many major tech platforms’ policies, the announcement was livestreamed by the pro-Trump outlet Right Side Broadcasting Network on mainstream platforms including YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. Afterwards in a press release, RSBN celebrated drawing four million views to their livestreams.

Fringe Platforms

Prominent “election integrity” figures cultivated audiences on fringe platforms who in turn amplified election-related conspiracy theories during early voting and Election Day, achieving significant cross-platform traction in some cases.

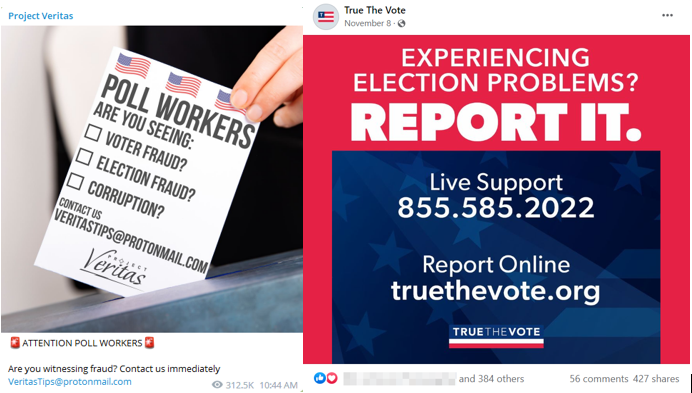

Prior to the election, ISD published an article about fear-mongering rhetoric about ballot drop boxes and calls for users to “take action” against them. ISD analysts observed that election-deniers and organizations, such as Project Veritas and True the Vote, used fringe platforms to call for civilian surveillance and, when necessary, vigilante-like reporting on election processes.

Figure 9: Project Veritas and True the Vote put out calls for their followers to report “election fraud.” The Project Veritas post was viewed 312.5k times on Telegram at the time of writing.

As early voting opened across the United States, influencers used Truth Social – a fringe website created by Trump – to quickly notify their audience of potential “wrong-doings.” Melody Jennings announced her national “election integrity” group Clean Elections USA and subsequently earned significant attention and support on the platform, including the attention of Trump. With that attention, Jennings boosted narratives alleging wrongdoing around ballot drop boxes and called for others to volunteer to watch and film the boxes. Though Jennings’ posts appeared on Trump social, analysts observed that her posts quickly spread across other fringe platforms, too.

Rumble, an alt-tech platform for posting videos and hosting livestreams, served as a popular platform for election deniers like Steven Crowder and TPUSA’s Kirk. Both hosted livestreamed podcasts during and after Election Day in which they hyped allegations of wrongdoing around voting. Crowder’s election coverage featured guests such as Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, pundit Ben Shapiro, former Arizona gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake, and the former president’s adult son Donald Trump Jr. According to Rumble, Crowder’s Election Day show drew more than 3 million total views alone. Kirk’s livestream drew just under a million viewers. ISD analysts observed both the hosts and guests peddling election disinformation and many viewer comments that pushed conspiracy theories, hate, and additional election disinformation.

‘Culture war’ messaging resonated online but didn’t move swing voters

Many Republican candidates across the country closed their campaigns with inflammatory and hateful messages that mirrored high-engagement right-wing media content online, but it proved unsuccessful in drawing voters, even by some election deniers’ own admissions. In one livestreamed podcast after Election Day, TPUSA’s Kirk and Arizona state Sen. Rogers debated whether Republicans had miscalculated their messaging because they exist in an “echo chamber.”

Transphobic and homophobic rhetoric was rampant in Republicans’ 2022 campaign messaging. Candidates and their supporters amplified extreme narratives, among them claiming that gender-affirming health care for children was inherently abusive and that drag queen shows and other LGBTQ+ events were meant to sexualize and abuse children. As such rhetoric has mainstreamed among Republican audiences, it has produced a steady stream of threats against children’s hospitals, drag shows, and LGBTQ+ spaces. Republican candidates also took extreme positions on issues like abortion; candidates like Michigan gubernatorial candidate Tudor Dixon and Georgia senate candidate Hershel Walker made hardline opposition to abortion access parts of their campaign messaging.

Figure 10: A Telegram channel used by Philadelphia members of the Proud Boys hate group shares a video clip of far-right influencer Jack Posobiec making an anti-LGBTQ smear at a rally for former Pennsylvania gubernatorial candidate Doug Mastriano.

Partisan media outlets amplified the same extreme rhetoric ahead of 2022 elections. A Media Matters analysis of Fox News broadcasts found that the network aired anti-LGBTQ+ attacks on more than half of the days in the first half of 2022, for example. An ISD analysis found that 18 Gateway Pundit articles about abortion published in October 2022 received an average of 466 comments, which is above-average engagement for articles on the website. Though it’s uncertain whether those partisan outlets were deliberately hoping to persuade undecided voters or strengthen extreme views among existing supporters, the messaging was unsuccessful in mobilizing votes in swing states.

By all appearances, election denialists and their candidates of choice misread the sentiments of voters, confusing high levels of online engagement with popular support. In Michigan, a proposal to amend the constitution to include a right to abortion passed with 56 percent of the vote. Users in online right-wing groups theorized after Election Day that Dixon’s support for a no-exception ban on abortion likely drove turnout against their candidates. The Michigan Republican Party also blamed Dixon’s focus on “transgender sports” as a reason for her loss.