The EU AI Act: Insights from the world’s first comprehensive AI law

20 March 2024

By: Terra Rolfe

The promises and perils of AI have dominated recent headlines and captured the imaginations of policy–makers around the world. Although there remains a lack of consensus on the nature and severity of AI-associated risks, the need for regulation is a common refrain. The European Union will be the first to pass comprehensive legislation in this area: on 13 March, the European Union’s AI Act (AIA) was endorsed in the European Parliament, one of the final steps before its adoption into EU law. The AIA will become the world’s first comprehensive AI regulation, the culmination of years of work from EU legislators and experts on responsible AI. It is a valuable first step towards AI regulation that upholds democratic norms and human rights, ensures tech accountability, and prevents misuse by bad actors, as well as minimising its role in mis- and disinformation. However, uncertainties and potential loopholes, particularly in regard to open-source AI and national security exemptions, remain.

The AIA: An Overview

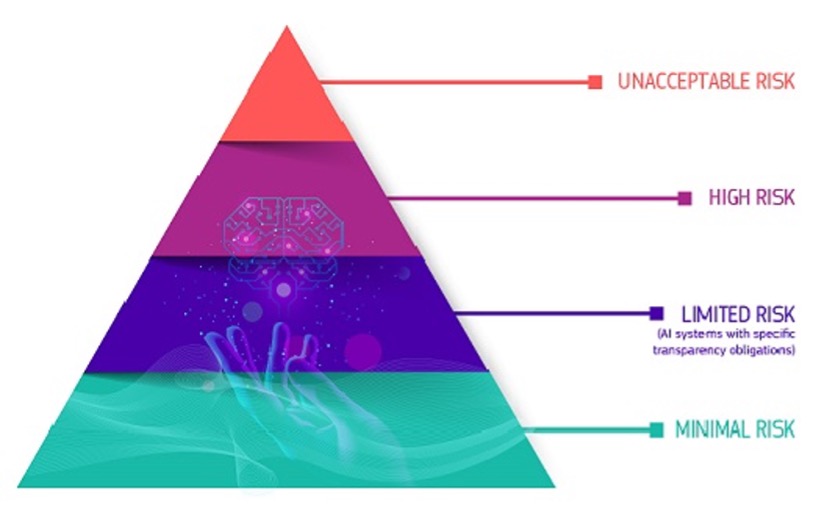

The AIA takes a risk-based approach to regulating AI. AI systems that pose higher levels of risk face the strongest requirements to ensure their safety and accountability. For example, high–risk systems — which pose the maximum allowed risk within the EU — face the most requirements, such as human oversight and a risk management system. Another set of use cases, including some biometric applications and ‘social scoring’ systems, are prohibited entirely due to the unacceptable risks they present.

The obligations of providers and deployers of AI systems will be enforced by national regulators (‘competent authorities’) within each EU Member State, as well as the European Commission through its newly established AI Office. Noncompliance with the regulations can lead to fines of up to 35 million EUR or 7 percent of annual company turnover worldwide, whichever is higher. The work of the AI Office and national regulators will be supported by a set of advisory bodies, including a scientific panel of independent experts and a multistakeholder forum of representatives from civil society, academia and companies of different sizes.

Figure 1. Risk levels of the EU AI Act. Source: European Commission (https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/regulatory-framework-ai)

Democratic Protections

The AIA’s requirements will introduce broad democratic protections against AI-driven harms, as well as specific measures to counter the spread of disinformation and misleading content through generative AI and deepfakes.

The prohibitions under Article 5 are important safeguards against the introduction and/or exacerbation of societal divisions, marginalisation, or undemocratic concentrations of power through AI. For example, systems using “subliminal techniques to […] distort behaviour and impair informed decision-making, leading to significant harm” are banned; such a ban is unequivocally beneficial to democratic functioning and the protection of fundamental rights. In addition, all systems involved in the administration of justice and democratic processes, including systems used for influencing electoral outcomes or voting behaviour, will fall under the high-risk category and be subject to its stringent accompanying requirements.

More generally, the AIA mandates transparency for almost all AI, a key obligation for ensuring accountability, promoting public trust, and facilitating effective oversight. This includes special obligations for General Purpose AI (GPAI) systems, the largest and most powerful type of AI; at present, this would likely include models such as OpenAI’s GPT-4. The transparency, accountability and enforcement mechanisms provided throughout the AIA are important steps towards ensuring a higher level of accountability for technology companies, ensuring a more equitable balance of knowledge and power between industry and society.

The AIA also introduces safeguards against abuse, bias and discrimination in AI through risk management and data governance obligations. These safeguards are important for preventing a wide variety of harms, which often align with and exacerbate existing patterns of systematic discrimination and marginalisation, such as racial or gender discrimination.

Disclosure, Deepfakes, Disinformation and the Digital Services Act (DSA)

The AIA introduces significant obligations for generative AI systems, which can produce realistic video, image, audio, and text content. Generative AI has been linked to a wide range of societal and democratic risks, including dissuasion of voters; online influence operations; creation of terrorist propaganda; chatbots designed to dehumanise marginalised groups and desensitise users; and the spread of non-consensual intimate images, which disproportionately affect women and girls and threaten their participation in public life.

Generative systems will be subject to a range of requirements designed to increase information integrity. The providers of generative systems must ensure that their outputs are marked as artificially generated or manipulated. This is intrinsically useful for users to determine content’s veracity and can also be used by social media platforms to label content. Deepfakes must be accompanied by a disclosure that the content is artificially generated or manipulated. When AI is used to generate text that will be directly published to inform “the public on matters of public interest” this must also be clearly disclosed.

Together, these obligations are significant attempts to move towards a more trustworthy and transparent information ecosystem. They are intended to help prevent issues that threaten democracy, societal cohesion and public trust, such as the spread of misleading information through political deepfakes and disinformation operations, as well as phenomena such as the ‘Liar’s Dividend,’ where people dispute the veracity of authentic but unflattering content by claiming it is fake.

Disclosure obligations for AI will also aid social media platforms in their mitigation of systemic risks under the DSA, such as those to democratic processes, civic discourse and elections. Clearly marked artificial content will allow platforms to better action their commitments to labelling AI-generated content, and users will have greater clarity on the origins of content.

The AIA also provides valuable clarity as to what elements of AI are regulated by the AIA versus the DSA. It outlines that Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and Very Large Online Search Engines (VLOSEs) that have AI embedded within their services will meet their obligations through the DSA’s risk management framework, unless new systemic risks not covered by the DSA emerge. Examples of such embedded systems include the machine learning algorithms used to rank posts on users’ Instagram feeds, or the integration of OpenAI’s GPT large language models into Bing Search.

Uncertainties and Risks of Exploitation

While the provisions outlined above show the AIA’s promise for safely and democratically regulated AI, uncertainties remain around its implementation and enforcement, including several potential loopholes that could be exploited by actors looking to avoid accountability.

The process of providers self-designating their systems as high-risk risks exploitation. Self-designation has the potential to increase legal uncertainty and diminish enforcement and accountability measures, although significant noncompliance fines may mitigate this risk. This issue has been recognised and warned against throughout the AIA’s drafting, including by the European Parliament’s legal office and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

In terms of general risks to fundamental rights, the decrease in prohibited use cases in the final AIA text risks permitting surveillance and enabling the marginalisation of vulnerable communities. The movement of some biometric use cases from the prohibited tier to high-risk, as well as the exemptions on the prohibition of real-time biometric identification, are particularly concerning. As already noted by Access Now, EDRi, and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the use of biometrics may lack proportionality against the fundamental right to private life. Its inclusion under the AIA will potentially also provide clarity and legal legitimacy to surveillance activities.

In addition, the AIA does not prohibit the use of emotion recognition systems in border control, policing and migration contexts. This is concerning as the evidence on these systems is mixed and even described as pseudoscientific. Additionally, the exemptions for these use cases intersect with particularly vulnerable and marginalised populations, such as migrants and ethnic minorities, who are already subject to racism and discrimination from police. Emotion recognition systems have general discrimination risks, as acknowledged in a warning from the UK Information Commissioner; there is a reasonable potential for these risks to be amplified when it comes to vulnerable populations.

The wholesale exemption of national security under Article 2 of the AIA also creates a loophole that risks exploitation. The exemption is rooted in the Treaty of the European Union (TEU), which enshrines national security as the sole competency of Member States. National security remains a vague and undefined term in the legislation and case law of the EU and most of its member states, as well as the European Court of Human Rights, which includes non-EU countries. The implication of this vagueness for the AIA is that states can potentially avoid oversight by claiming that they are using AI for ‘national security’ purposes. The risks of this range from abusing the term to enable surveillance, to more mundane – but still potentially harmful and discriminatory – examples such as unregulated AI for hiring, as noted by a range of legal and digital rights organisations.

Lastly, the regulation of open-source AI remains an area of uncertainty. While important for innovation, open-source systems have been linked to a variety of harms, including radicalisation and the amplification of hateful and abusive language. Most open-source AI is excluded from the AIA, unless it qualifies as prohibited, high-risk or GPAI with systemic risk. While including open-source AI in these categories is beneficial for mitigating harms from the most dangerous systems – and narrower and arguably riskier exclusions were considered during negotiations – uncertainties remain regarding enforcement. Regulating a diffuse group of individuals and entities, often working independently, with significant variations in their actions and intents, will likely pose greater difficulties to enforcement. For example, identifying an open-source system modified to be high-risk by an individual and enforcing the relevant requirements in the AIA will likely be significantly more challenging than enforcement against a company. Further delegated acts and/or guidance from the AI Office will be needed to establish clarity on how open-source will be regulated and enforced in a manner that prevents harms.

A glossary of terms in the EU’s AI Act can be found here.