Online Extremism Index: Slovakia

7th December 2021

By Richard Kuchta

Launched by ISD at the UN General Assembly in 2015, the Strong Cities Network (SCN) is the first global network of local leaders dedicated to combating hate, polarisation and extremism in all its forms.

As part of the SCN’s programme of ongoing research, ISD analysts have mapped and analysed the online extremist landscape in Bangladesh, Kenya, Slovakia, the Maldives, North Macedonia and Central Asia. The purpose of this research is to inform comprehensive, evidence-based responses to these online harms.

This Dispatch examines the online threat landscape in Slovakia.

_______________________________________________________________________

The online extremist landscape in Slovakia

In the last decade, far-right extremism has become increasingly mainstreamed in Slovakia, with one far-right party having been repeatedly elected to representative bodies on local, regional and national levels. Online, far-right actors lead successful communication campaigns on social media, where they reach large audiences who subscribe to hateful and hostile content aimed at political representatives and minorities. These actors have exploited COVID-19 to further polarise society by spreading disinformation and conspiracy theories about the pandemic and vaccination. They were able to mobilise diverse communities including anti-vaccine activists, conspiracy theorists and football hooligans, and attended several protests in the Slovak capital Bratislava which led to violent attacks against journalists and others.

ISD’s research identified 375 pages, groups, accounts and channels on Facebook, Instagram and Telegram spreading extremist content, which was detected in 11,779 posts during the eight month monitoring period. Most instances (108) were associated with the far-right party Kotlebovci-ĽSNS, which was followed by radical right (92) and extreme right actors (82). Extreme right actors subscribe to ideas of racial, ethnic or cultural supremacy which are incompatible with pluralist democracy, and want such a system to be implemented. Radical right actors subscribe to the same ideas, however do not implicitly or explicitly ask for this supremacy to be implemented in ways that would alter the political system.

Conspiracy theorists and alternative media outlets were also found to spread extremist content, indicating the hybrid extremist threat landscape in Slovakia. All of these actors showed a strong affinity for nationalism, visible in the images they chose to represent their groups, such as the Slovak emblem or double-cross associated with the totalitarian regime of the Slovak state during World War II. Keywords associated with nationalism were detected in 49% of posts. While posts including nationalist narratives focused on the in-group, other detected narratives showed slurs and hateful language against specific groups or minorities. The most prevalent forms of hate in our dataset were anti-LGBTQ+ (16.53%), antisemitic (14.38%) and anti-media (11.82%) language.

Most actors and messages were identified on Facebook. This platform plays a crucial role for extremists, possibly due to the large number of Facebook users in Slovakia and the unwillingness of extremists’ followers to move to other platforms. Facebook’s large user base affords extremists a wider reach and potential for the mainstreaming of their ideologies. Extremists also adopted language changes, using new terms and codes to avoid content moderation or legal consequences. For example, where they used to refer to the Roma minority as “Gypsies” in the past, now they refer to Romas as “settlers”.

Possibly in response to content moderation, some actors have moved to Telegram, which is largely unmoderated. Content used on Telegram was more extreme than on Facebook, with actors openly sympathising with extremist ideologies (image 1). Telegram appears to be a new platform for Slovak extremists, with11 out of 17 channels created in 2021.

Image 1: Post in a Telegram channel (translation: one picture for 1000 words).

Far-right parties online

Kotlebovci-ĽSNS is a far-right party in Slovakia. The party succeeded the banned extremist organisation Slovenská Pospolitosť and made a breakthrough in 2013 when its leader Marian Kotleba was elected as governor of the Banská Bystrica region. Kotleba and his party capitalised on their success and were elected to the Slovak parliament in 2016. Even after being elected, some members of Kotlebovci-ĽSNS were charged for promoting extremist ideology.

Kotlebovci-ĽSNS used to play a crucial role within the Slovak far-right right scene. However in early 2021, following conflicts within the party, some members left to start a new political party called Republika. This led to a decrease in the reach and impact of Kotlebovci-ĽSNS on the Slovak far-right. Both Kotlebovci-ĽSNS and Republika featured prominently in our dataset, alongside the party Slovenské Hnutie Obrody. While Kotlebovci-ĽSNS and Republika have electoral prospects, Slovenské Hnutie Obrody has an outsider role among these three far-right parties.

Differences in the online presence of political parties

Data from ISD’s research allows us to compare the online activity of the different political groups. Kotlebovci-ĽSNS have a robust presence on Facebook, with 90 pages and 16 groups associated with the party. Only two identified accounts on Instagram are associated with them, demonstrating that Facebook is their key communication platform. Some of these pages were created even before Marian Kotleba was elected in 2013.

However, most of these pages and groups were created around the parliamentary elections in 2016. These pages belong to regional structures, party members and fan pages supporting the party. Thanks to this structure, Kotlebovci-ĽSNS were able to keep their audience despite several bans on their main Facebook page. Although ĽSNS announced a move to the Russian platform VK in 2017, this move was not successful: many followers remained on Facebook, and ĽSNS accounts on VK.com show only limited activity. Small groups of pages showed signs of coordinated activity, sharing identical content at close time intervals. One of these groups appears to be operated by one or two accounts that shared identical content at short intervals in different Facebook groups.

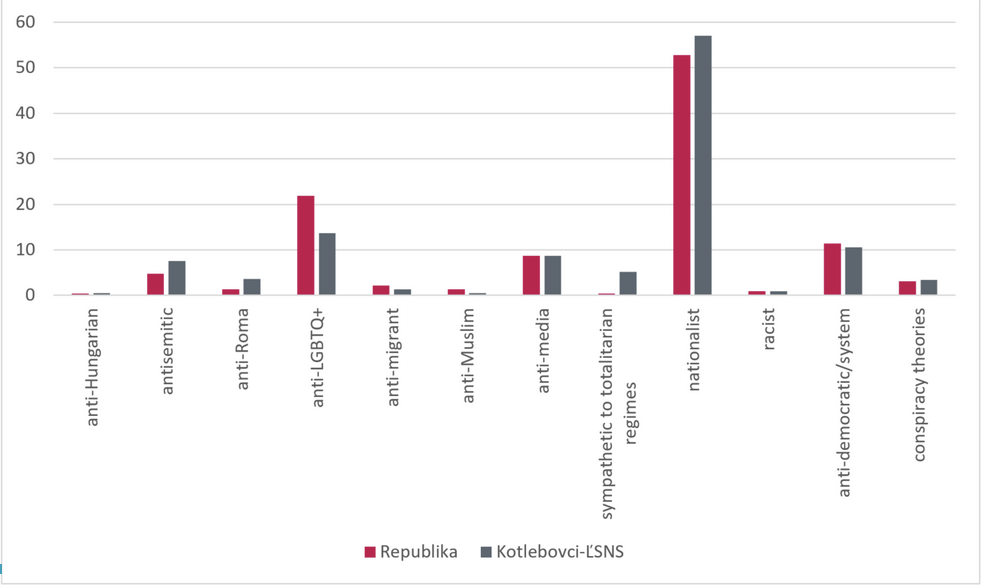

Figure 1. Comparison of narratives by Republika and Kotlebovci-ĽSNS.

Republika was only created in 2021, and its comparatively simple online presence reflects this. However, several members have large individual followings which are used to propagate the party. In contrast with Kotlebovci-ĽSNS, Republika focuses their communications on one central page, with content then shared by members. Republika is more active on other platforms, with accounts on both Instagram and Telegram. Despite claimed differences between Republika and Kotlebovci-ĽSNS, ISD’s analysis showed only small differences in topics discussed by the two parties. One key difference appears to be in the kind of hateful and polarising narratives spread by each party. Republika pages tended to spread anti-LGBTQ+ narratives, while Kotlebovci-ĽSNS instead promoted nationalist, antisemitic, and anti-Roma narratives, as well as narratives sympathetic to totalitarian regimes.

The third party, Slovenské Hnutie Obrody, applies a mixture of strategies. They have a central Facebook page, Facebook pages for regional structures, and Facebook pages for party members. Content from these latter groups of pages was mostly re-shared from the central Facebook page. SHO-affiliated channels were also identified on Telegram, suggesting an attempt to gain traction on multiple platforms. Content shared by accounts associated with Slovenské Hnutie Obrody was primarily nationalist in nature, with a substantial proportion containing anti-LGBTQ+ and anti-democratic/system narratives.

Conclusion

ISD’s analysis, covered in depth in the full report, highlights a diverse community of actors promoting hateful and exclusionary content online. In addition to individuals associated with radical politics, conspiracy theorists, anti-vaccine activists and alternative media outlets promote such content.

The research provides fresh insight into the online extremist environment in Slovakia. It can be used by national, municipal and civil society stakeholders to inform the development of effective offline prevention approaches. Beyond this, through identifying emerging trends it provides an initial baseline for further analysis by those studying the Slovak hate, disinformation and extremism landscape.