On Facebook, Content Denying Russian Atrocities in Bucha is More Popular than the Truth

20 April 2022

An ISD study of Facebook posts across 20 countries found that three weeks after the Bucha massacre, the most shared Facebook posts on the events are the ones questioning it.

_________________________________________________________________________________

As Russian troops withdrew from the Ukrainian city of Bucha on 30 March, people across the world were shocked by images of the atrocities left behind. However, as international media showed footage of countless civilian deaths and covered testimonies of the survivors, Russian state-media and state officials were quick to offer their alternative version of the events.

This included pro-Kremlin sources sharing footage coming from Bucha alongside claims that the dead civilian bodies in the streets were fake, questioning the timeline of the events, and accusing Ukraine and its Western partners of having staged a massacre with the aim of jeopardising Russia’s reputation.

Image 1: A post shared by the Russian Embassy in Jamaica claims a corpse on the streets of Bucha can be seen moving.

As social media filled with different interpretations of the events in Bucha, ISD analysts conducted a research study to establish which narratives about the events were gaining the most traction online in different countries both in and outside Europe.

Based on the in-house language capabilities of our analysts, we analysed the top ten most shared posts about Bucha on Facebook in 20 countries: 14 EU countries (Austria, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, and Spain), the UK, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, the US and Venezuela.

Methodology

Using CrowdTangle, we identified and analysed the ten most shared posts on Facebook mentioning Bucha (and different spelling variations of ‘Bucha’ based on different languages) in each country between 30 March 2022 to 6 April 2022, analysing a total of 200 posts. This timeframe corresponded with the withdrawal of the Russian troops from Bucha and the subsequent discovery of dead civilians left in the streets of the town.

Rather than selecting the most popular posts in each country based on the ‘Page Admin Country’, we selected the ‘local relevance’ of the posts, as this would include posts from pages that are not necessarily administered from the country but would reach local audiences. The local relevance of a page, as clarified by CrowdTangle itself, does not include all of the most popular content for a location but instead shows posts from pages with a high proportion of followers in the area selected. One example of this is the Spanish language page of RT. The page is managed by administrators based in Russia, Spain, Mexico and Argentina but reaches a wide audience in other Spanish-speaking Latin American countries.

For each post, we coded whether or not the content was pro-Kremlin, the source of the post, and whether the content of the post raised doubts over the legitimacy of the images shown from Bucha by Western mainstream media. Content was categorised as pro-Kremlin if an explicit pro-Kremlin bias was found, including featuring only the Russian narrative of the facts or providing explicit support to the Russian official narrative.

Posts were further categorised as doubting the legitimacy of the images from Bucha or the mainstream narrative when they questioned the timeline of the events, suggested that Ukrainians might have committed the crimes or claimed that the scene in Bucha might have been staged.

Key findings

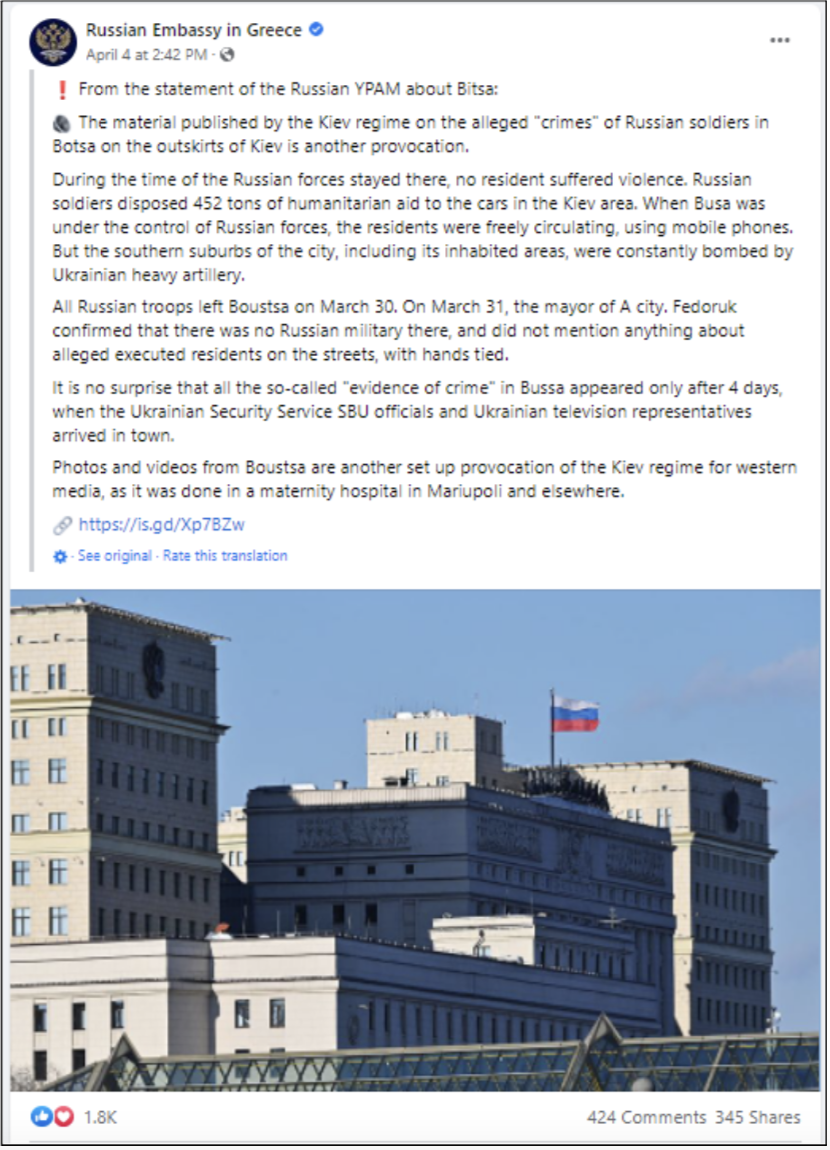

➜ Of the 200 posts analysed, 44 displayed a pro-Kremlin bias and 6 had been posted to pages tied to either Russian state media or Russian Embassies.

➜ 55 of the posts analysed (27.5%) cast doubt on the legitimacy of images from Bucha used by Western mainstream media.

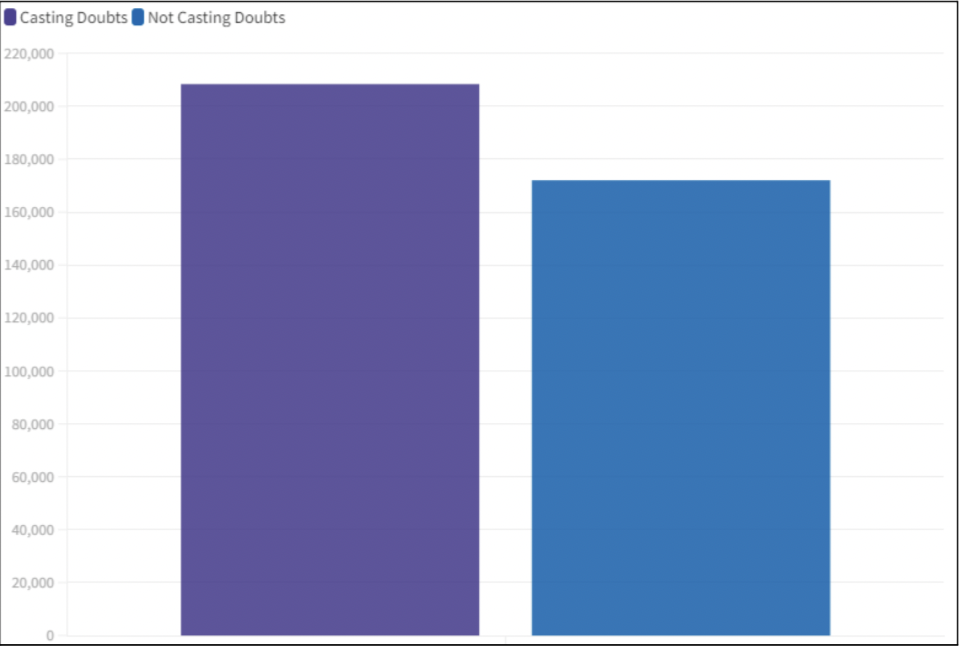

➜ The 55 posts that cast doubt on the mainstream narrative about the atrocities in Bucha gained significantly more traction online than those that did not question the mainstream narrative. The 55 posts had a total of 208,416 shares, whilst the remaining 145 posts had a total of 172,063 shares.

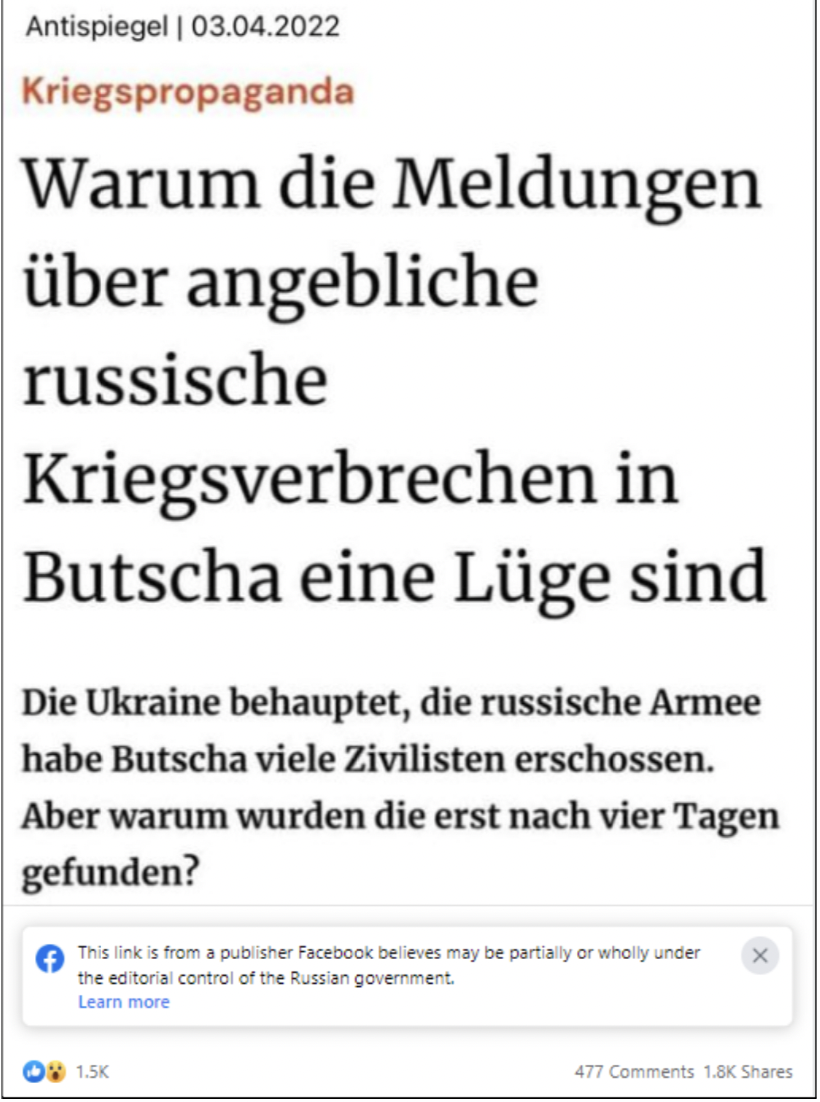

➜ None of the posts analysed contained a fact-checking label. Only 2 posts contained a label which referred to the source, stating: “This link is from a publisher Facebook believes may be partially or wholly under the editorial control of the Russian government” (see Image 11).

Pro-Kremlin posts

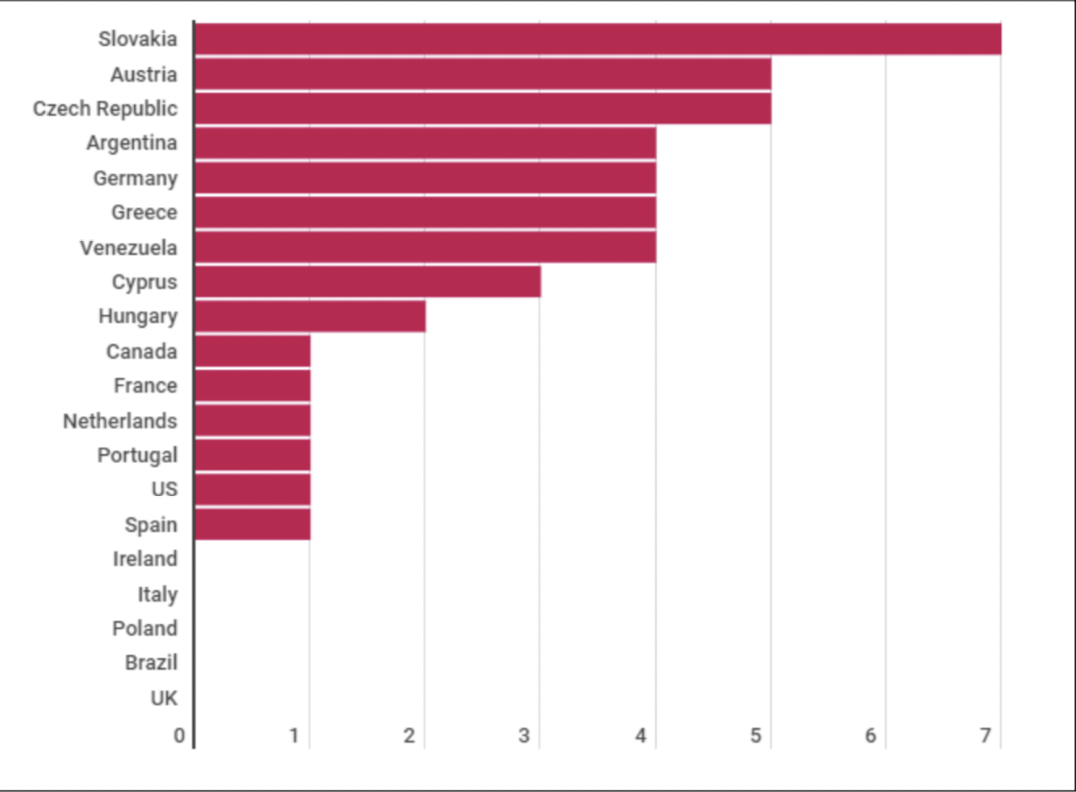

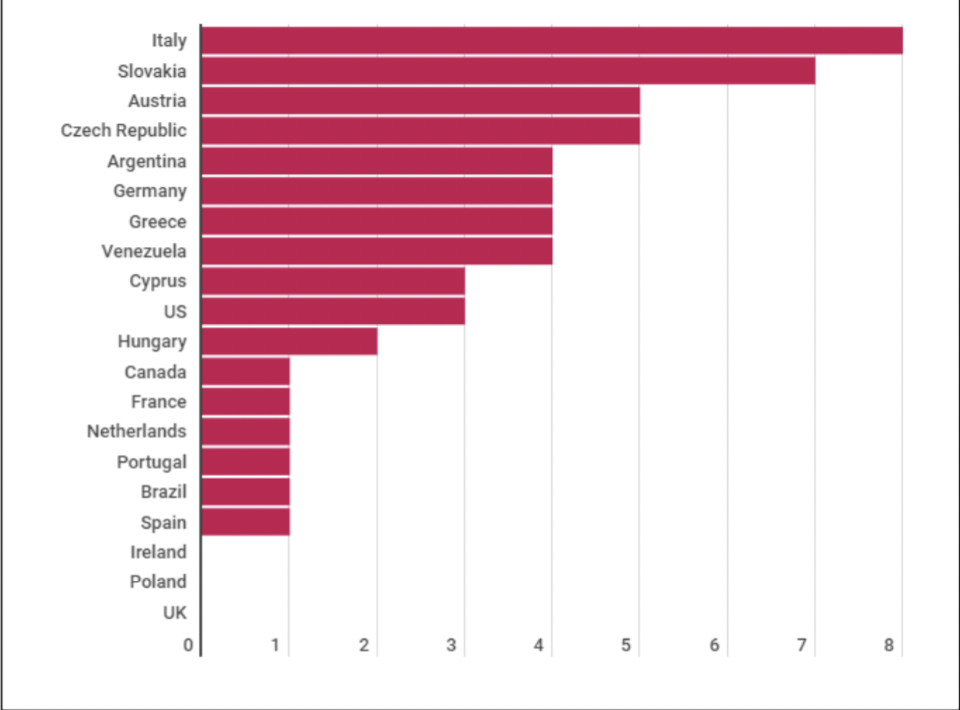

44 of the 200 posts had a pro-Kremlin bias, and originated from pages tied to either Russian state-media or officials or from pro-Kremlin sources. Although Russian state media have been banned from social media in the EU, a pro-Kremlin interpretation of the events in Bucha was found in 34 posts across ten EU countries. In Slovakia, seven of the ten most shared posts on Bucha included pro-Kremlin narratives. Additionally, all but one of the ten most shared posts in Slovakia had been posted to Facebook pages known for their anti-establishment, extremist or populist positions, and for spreading hate speech and disinformation. This finding is concerning; it illustrates how illegitimate sources are outperforming mainstream media and official sources in the coverage of the massacre in Bucha.

Two other European countries where pro-Kremlin narratives were widely shared on Facebook were Austria and the Czech Republic, where half of the posts analysed contained a pro-Kremlin bias. In Austria, the four most shared posts were all pro-Kremlin, and three of them came from the anonymous blog ‘Prüfe alles, glaube wenig, denke selbst’ (“Verify everything, believe little, think for yourself”). The most shared post in Austria was the same as the third most shared post in Germany, and analysts identified that the text of the post had been copied from a known pro-Kremlin disinformation outlet called Antispiegel. Echoing a Russian interpretation of the events, the posts cast doubt on the timeline of the massacre and suggested that the victims had actually been killed by the Ukrainian army as a punishment for their support of the Russian army.

Among the 44 posts that included a pro-Kremlin narrative, six had been posted by Russian state media or officials. In Venezuela, the two most shared posts, and three of the top ten, came from the Russian state media RT.

Image 2: The number of pro-Kremlin posts in each country.

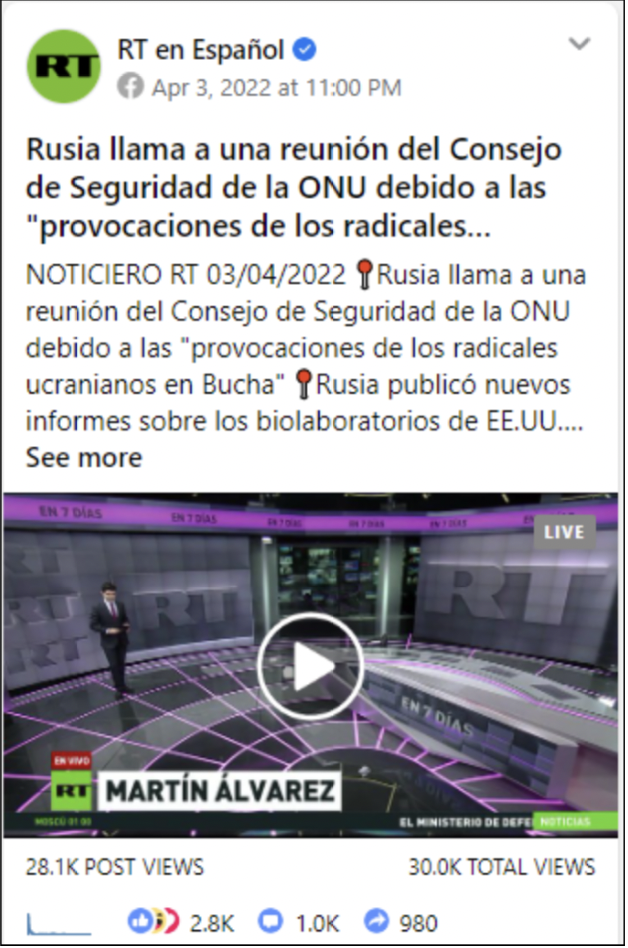

Image 3: Most shared post in Venezuela with 980 shares and 30K views calls the massacre in Bucha “provocations by Ukrainian radicals”.

Translation: ‘Russia calls a UN Security Council meeting due to “provocations by Ukrainian radicals in Bucha”’.

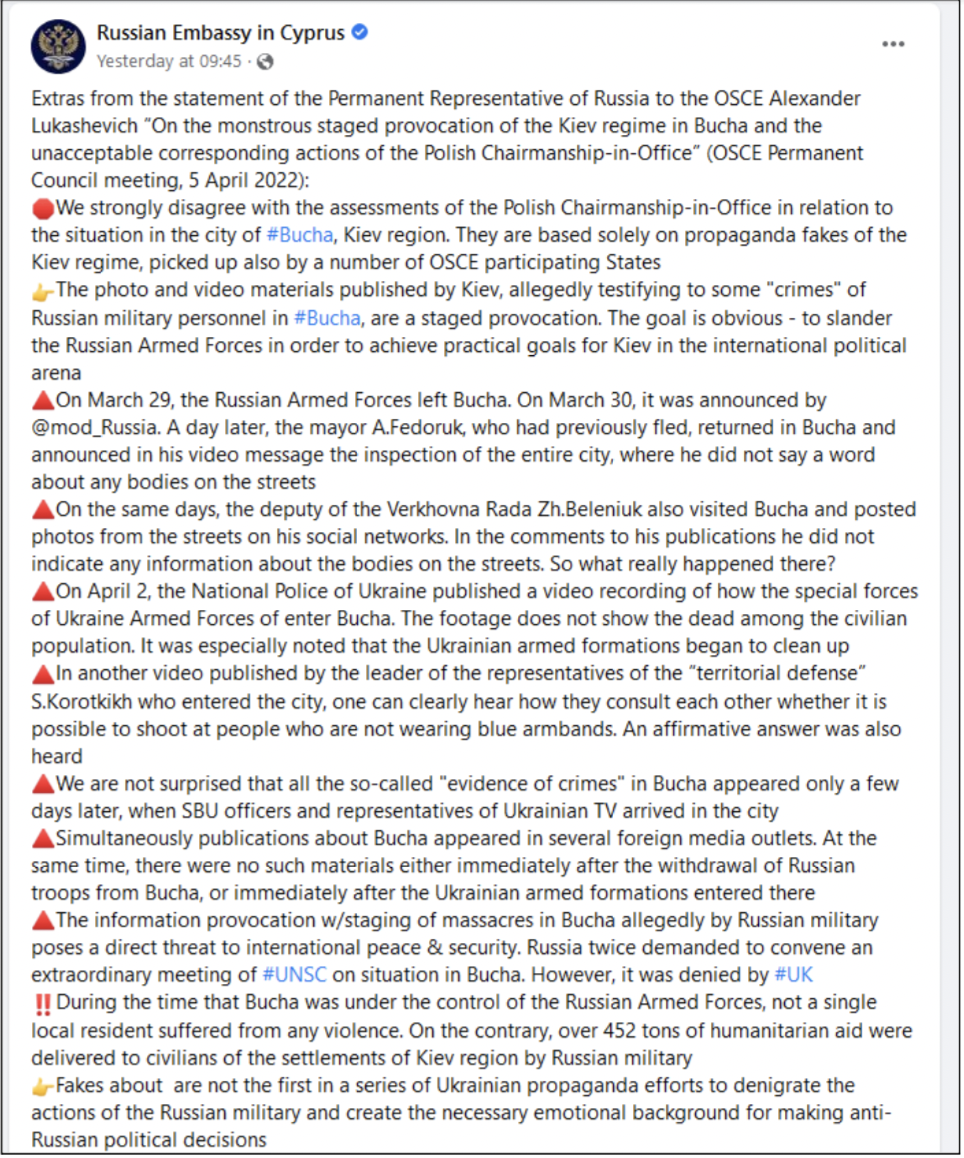

In Cyprus and Greece, posts from the local Russian Embassies were found to be among the top ten posts about Bucha. In Greece, both the second and the sixth most shared posts came from the Russian Embassy, and called the images from Bucha a “provocation”. Similarly, the third most shared post in Cyprus was from the local Russian Embassy. It claimed that the images of the massacre represented a “staged provocation” with the goal of slandering the Russian Armed Forces. The post also denounced “intentions to destroy everything Russian” and “calls for violence against Russian”, including threats to “kill all Russian children” (see Image 4).

Image 4: The third most shared post in Cyprus posted by the local Russian Embassy.

Another state-media outlet that was found to consistently post pro-Kremlin content was the Facebook page of the Latin America television network teleSUR. The network is primarily funded by the government of Venezuela and has been accused of being a propaganda tool for Hugo Chavez. Posts from teleSUR were among the most shared posts in both Argentina and Venezuela, with 2 and 1 posts respectively. These posts contained an exclusively Russian interpretation of the events, failing to represent the other side of the story.

Image 5: One of the most shared posts in Argentina features an article titled “Russia accuses the West to support the staging of Bucha in Ukraine”.

Translation: ‘The spokesperson for the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Maria Zakharova, warned on Wednesday that if the West supports the staging of the events in Bucha as real it will also take part in this criminal action’.

Casting doubts on the massacre

In addition to posts exhibiting an explicitly pro-Kremlin narrative or only presenting a Russian interpretation of the events in Bucha, many posts also cast doubt on the legitimacy of the images being shared on mainstream media or on the timeline of the events. Posts of the latter suggested that the scene might have been staged after Russian troops withdrew from Bucha.

These posts could not always be characterised as pro-Kremlin and made up 55 of the 200 most shared posts in 17 countries. Although only comprising 27.5% of the total number of posts, they accounted for the majority of the overall number of shares, obtaining 208,416 shares in total. This surpassed the number of shares (172,063) obtained by the 145 posts that did not cast doubts on the images.

Image 6: The number of shares obtained by posts that cast doubt on the mainstream narrative versus posts that did not cast doubt on the events. In total, the 55 posts that doubted the narrative obtained 208,416 shares, and the 145 posts that did not doubt the narrative obtained 172,063 total shares.

Examples of such posts were largely found in Italy, where 8 of the 10 most shared posts had either originated from the official Facebook page of Italian war reporter Toni Capuozzo or mentioned a controversial interpretation of the events by Capuozzo. Capuozzo’s interpretation, which had been picked up by Italian media and shared widely on Facebook, claimed that the footage of dead civilians in Bucha only appeared in the media a few days after the withdrawal of Russian troops, and that their deaths might therefore be attributed to Ukrainians as well as the Russian military.

Capuozzo’s posts alleged inconsistencies between the images and the mainstream narrative of the massacre, and cited a lack of blood on the streets and the fact that Bucha’s mayor did not mention the bodies in a video published after the withdrawal of Russian troops as evidence.

His claims can easily be debunked. On 7 March, during an interview with AP News, Bucha’s Mayor Anatol Fedoruk spoke about the bodies of dead civilians on the streets of the town, stating: “We can’t even gather up the bodies because the shelling from heavy weapons doesn’t stop day or night.”

None of the most shared posts in Italy came from mainstream media. Of the two posts which were not related to Capuozzo, one was critical of the amount of attention being given to the war in Ukraine compared with the war in Syria, and one was a post from the blogger Nicola Porro denouncing claims of rapes by Ukrainian soldiers.

Image 7: The number of posts that raise doubt about the legitimacy of the images from Bucha.

Similarly, in Spain, the most shared post about Bucha came from the Spanish YouTuber Ruben Gisbert who entered Donbas from Russia at the beginning of the war, in order to allegedly tell the truth about the conflict. Gisbert’s post contained a video in which he argues that the images from Bucha might have been staged, and the killings in Bucha may have been committed by Ukrainians rather than by Russians. His video was subsequently picked up by RT, and became the second most shared video about Bucha in Venezuela.

Image 8: The most shared post about Bucha in Spain comes from the YouTuber Ruben Gisbert and raises doubts about mainstream reporting on the massacre. The video caption reads “corpses found in Bucha (Ukraine)”.

Facebook’s failure to add fact-checking labels

None of the 200 posts analysed contained a fact-checking label on their content. Only two posts had a label at all, and the label on each referred to the source of information rather than the content of the post itself, stating: “This link is from a publisher Facebook believes may be partially or wholly under the editorial control of the Russian government”.

These two posts contained links to content from the previously mentioned blog ‘Prüfe alles, glaube wenig, denke selbst’ (‘Verify everything, believe little, think for yourself’). None of the other posts coming from Russian or pro-Kremlin sources included a similar label.

Image 9: A post from the Russian Embassy denying that Russian troops committed any violence during the occupation of Bucha was among the most shared on Facebook. The post does not contain any label neither on the account, nor on the content.

Image 10: The second most shared video in the US about Bucha with 25,900 shares states, “The reality about the massacre in Bucha has been found, civilians were killed by Ukrainian neonazis in order to blame the Russians”. The post does not feature a fact-checking label.

Image 11: The only label found in the 200 posts analysed was in a post shared in the Facebook group “Prüfe alles, glaube wenig, denke selbst”. The post reads “Why the messages about alleged Russian war crimes in Bucha are a lie. Ukraine claims that the Russian army has shot many civilians, but why were these found only after four days?”.

Conclusion

In the aftermath of the Bucha massacre, Facebook has witnessed an information war fought over different narratives of the events. Despite extensive fact-checking, interviews with witnesses and survivors, and on the ground reporting of the atrocities that took place in the Kyiv suburb, the posts that obtained the most shares on Facebook were those raising doubts about the veracity of the images.

This finding is concerning, as it shows that bloggers, disinformation pages and alternative media are achieving significant success in amplifying pro-Kremlin narratives and shaping the discourse around the war on social media. The case of Bucha stands as just one example of how a significant event in the war can be reframed to shift the blame away from Russia and question the veracity of the massacre altogether.