#IstandwithRussia – Anatomy of a Pro-Kremlin Influence Operation

8 March 2022

By Carl Miller & Jeremy Reffin

The #IstandwishRussia and #IstandwithPutin hashtags have the hallmarks of an influence operation masquerading as a grassroots social movement.

We ask: In the coming days, how can we detect the next operation?

_________________________________________________________________________________

In the days before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, a series of hashtags began to emerge on social media that managed to be simultaneously surprising and predictable.

As the invasion began, in the UK and around the world, #IstandwithPutin and #IstandwithRussia began to trend on Twitter. What was going on? Was some deep bedrock of pro-Kremlin solidarity finding its voice?

Figure 1: #IstandwithRussia and #IstandwithPutin trending on Twitter.

The Times seemed to think so, reporting that the hashtags were also trending in India, and noting “a strong strain of anti-Americanism” in the country.

To those of us who work on platform manipulation, however, there was nothing surprising in seeing #IstandwithRussia lurch into view. From elections and summits to conflicts and full-blown wars, we’ve watched for years as a tradecraft has developed. Alongside air, sea, land and space, information too is a theatre of war. What we were observing seemed to be a manouever in that theatre.

Sure enough, research began to emerge looking at the behaviour associated with these hashtags. In one thread, Marc Owen Jones pointed to a spam network using the hashtag to try to sell electronics. The voices they were amplifying, he explained, were often flimsy, day-old accounts containing stock images, with suspiciously high engagement rates and coherent messaging.

All of this points away from a genuine social movement online and towards an influence operation pretending to be one. It sported a signature array of tactics: inauthentic identities, real voices, automated amplification and carefully choreographed messaging.

It is never going to be more important to spot information warfare than in the days ahead. With this in mind, we wanted to take a look at #IstandwithRussia from a different angle. We have been interested in how this operation built up in the days leading up to the invasion, and as the tanks rolled over the border. What – we asked ourselves – can we learn from an operation that has been detected, so as to help us spot the next one?

Leading up to 24 February: Stage One: Initiation

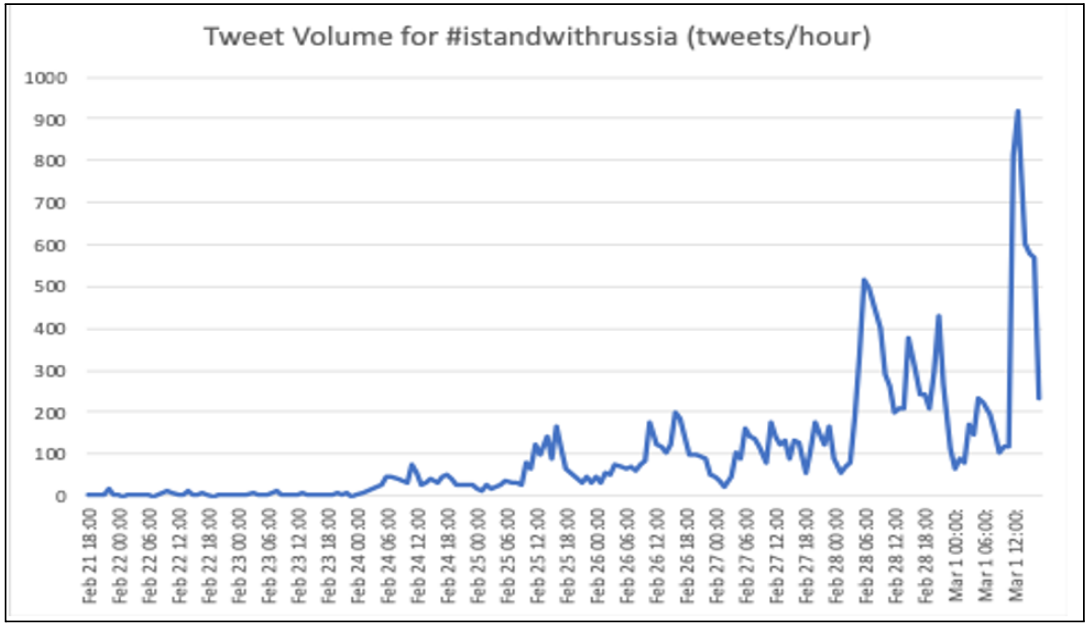

Figure 2: Volume of tweets per hour containing the hashtag #IstandwithRussia.

From 21 – 24 February, activity began to trickle onto Twitter. There were only 116 tweets containing the hashtag #IstandwithRussia sent over this time, entirely from obscure voices, and with only 76 retweets, they were mostly ignored. There was a middle-aged man in Perth, a young Italian man flying the Russian and Italian flags together in his profile picture, and an Indian currency trader. There’s a British voice too, with a display picture of a roaring lion.

Yet, scattered around the world as they were, they all behaved in a similar way. They railed against woke culture, political correctness or COVID-19 vaccines just a month ago, but suddenly all pivoted into wall-to-wall pro-Kremlin memes. Our guess? Domestic voices that had previously been deployed to focus on amplifying wedge issues were now being re-purposed to a more urgent requirement.

24 – 26 February: Stage 2: Amplification

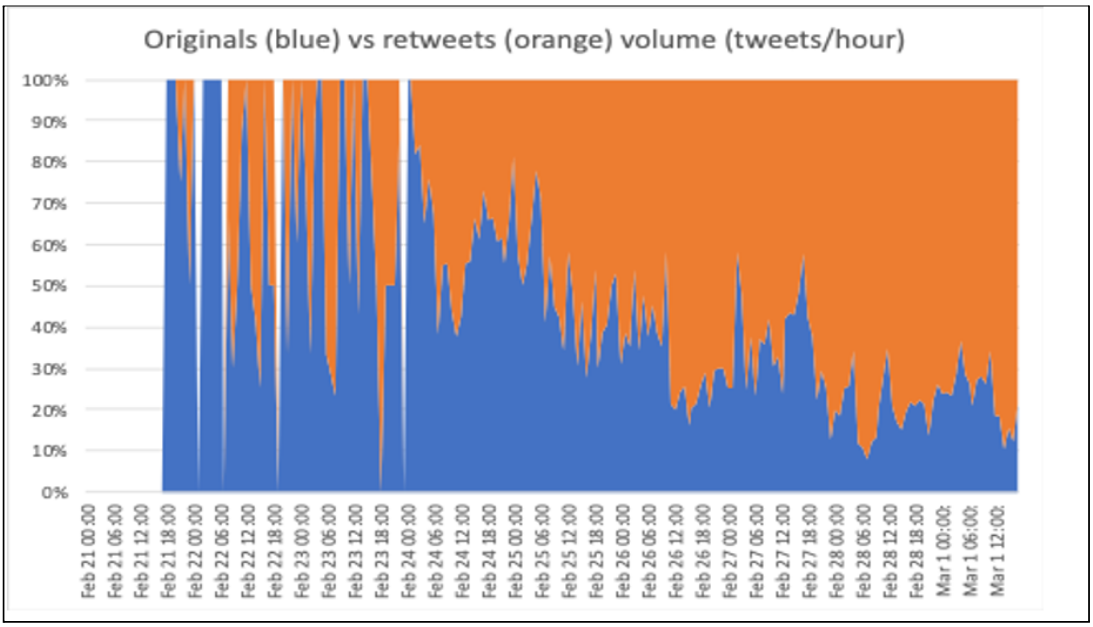

As the hashtag started to gain some traction, retweets became a larger and larger part of the picture. The next two days saw 2886 tweets and 1510 more retweets.

Figure 3: Volume of original tweets (blue) and retweets (orange) per hour.

This increasing amplification is probably the result of two different parts of the campaign coming together. First, there are the spam networks that Marc Owen Jones noticed. They create a whole string of messages that have far higher levels of engagement than we’d expect given the number of followers they have.

Second, larger accounts start to use the hashtag in this time period. This includes the now-suspended account @KVajpayaee, who tweeted the hashtag 81 times to his 47,000 followers over these two days.

As these strands come together, the campaign looks more complex on the surface. You seem to have big, thundering pro-Kremlin messages, surrounded by the clamour of grassroots pro-Kremlin voices all over the world. By social media standards however, everything we’ve seen so far is still very small and inconspicuous.

The change comes as the campaign moves into Phase 3.

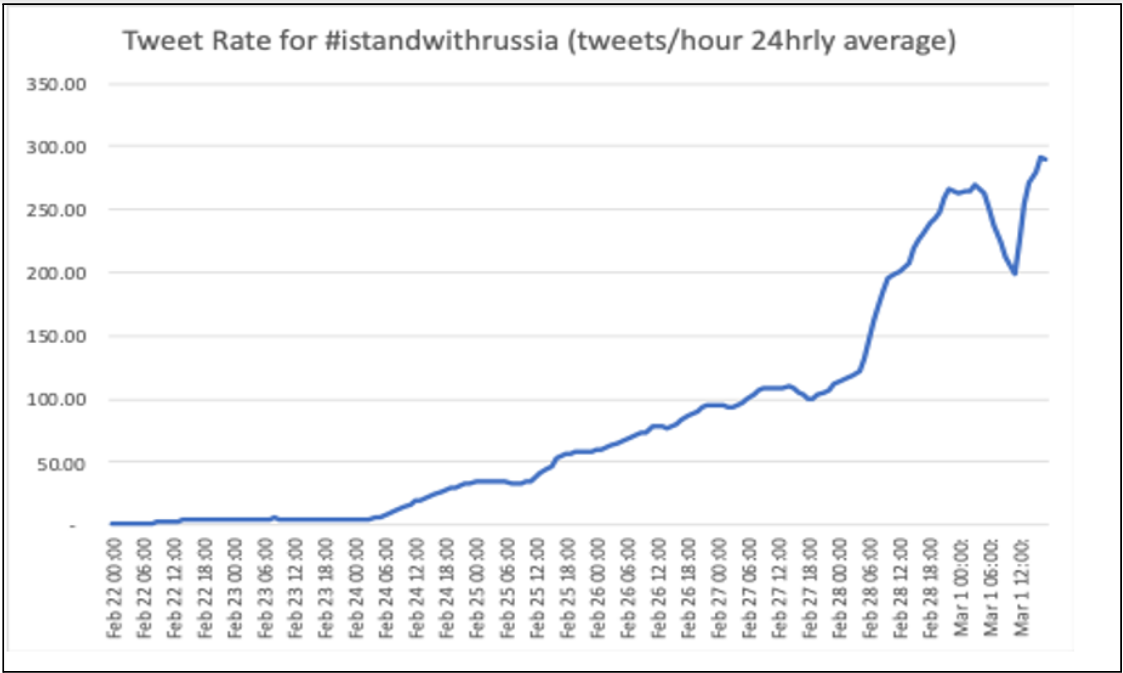

26 February Onwards: Phase 3: Breakout

Phase 3 begins on 26 February, when a far more influential voice used the hashtag for the first time: @DZumaSambudla. This account claims to be Dudu Zuma-Sambudia, the daughter of former South Africa President Jacob Zuma. With 192,000 followers, @DZumaSambudla began to attract more amplification than anything we had seen in the previous few days.

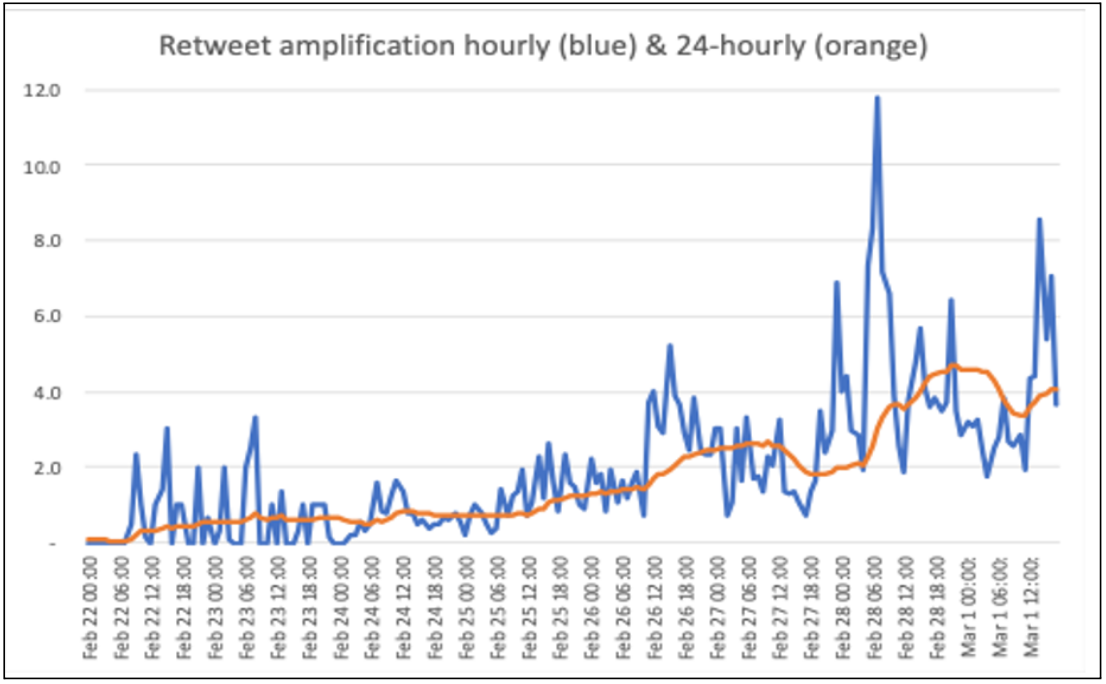

We cannot say whether this was planned or coincidental, but @DZumaSambudla’s use of the hashtag kicked off a phase of steepening amplification in the days that followed, with 3,474 tweets and 12,568 retweets in the 4 days from 26 February – 1 March.

Figure 5: Number of tweets published per day containing the hashtag #IstandwithRussia.

Dudu Zuma-Sambudia really drove the hashtag during this breakout stage, sending 9 of the 20 most shared messages over the five days from 26 February; the sharp spikes observed in Figure 6 generally come from messages he sent.

Eventually, on 1 March, the campaign hit pay dirt with a tweet from the genuine Twitter account of the Kenyan blogger and controversialist Robert Alai, who boasts 1.7 million followers.

Figure 6: The hourly (blue) and daily (orange) retweet amplification rate for the hashtag #IstandwithRussia. The retweet amplification rate (vertical axis) is the ratio of retweets per tweet to the number of overall followers.

4. Peak and Takedown

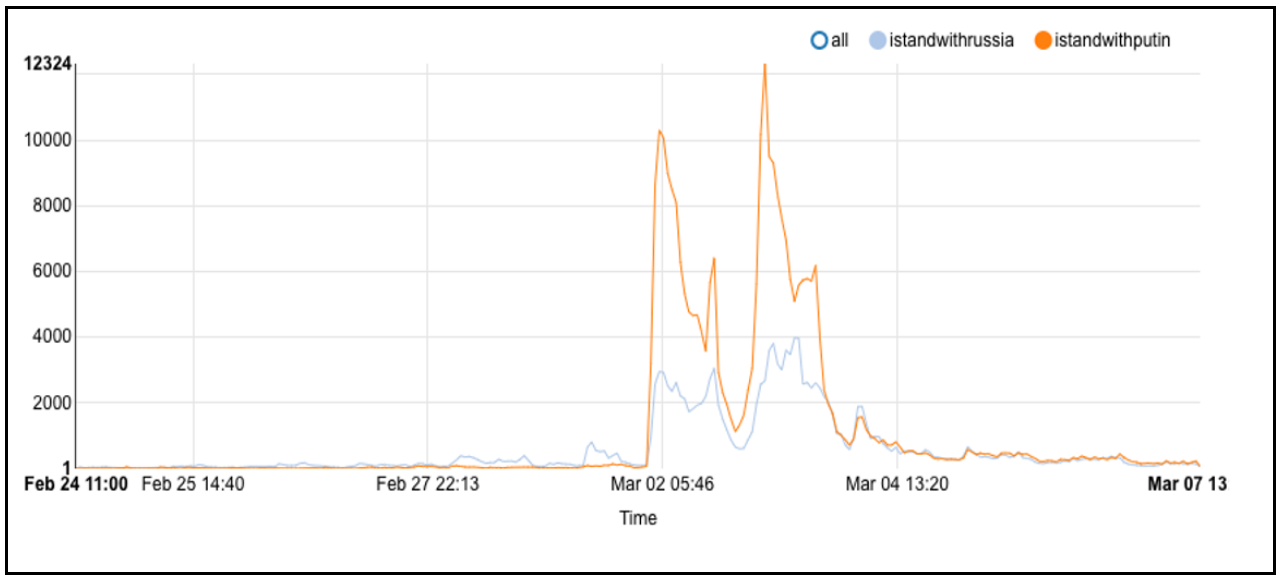

In the days that followed, the hashtag soared, reaching a total of 153,558 tweets between 24 February – 7 March. Even at this scale, however, it was just part of a broader campaign, and really just the smaller brother of #IstandwithPutin, a hashtag which reached far higher peaks of volume on the main days of its activation.

Figure 7: Volume of tweets over time containing the hashtag #IstandwithRussia (blue) and #IstandwithPutin (orange).

On 4 March, we watched as Twitter responded to the operation. Of the first 80,000 tweets using either #IstandwithRussia and #IstandwithPutin, only 26,000 – we think – remained on the platform. Russia had bought in, activated and ultimately burned its assets to make those hashtags trend; now it would lose many of them to take-downs and suspensions.

This brings us to what was surprising about the hashtag: it actually worked. On the face of it, this operation was crude and transparent enough to be called out by researchers within days of being thrown into operation.

But by the time it had been identified, the network had already achieved what it likely set out to do. It had, via the trending box on Twitter, got #IstandwithRussia into the pages of The Times.

There are lessons here for all of us. Twitter shouldn’t have let it trend, journalists shouldn’t have uncritically written it up. The conflict in information is only going to intensify and every time an operation like #IstandwithRussia rolls out, we have to make sure it gets less effective.

Carl Miller & Dr Jeremy Reffin are both Partners at CASM Technology.

* This article was updated on the 11 March to reflect that the Twitter handle @DZumaSambudla allegedly belongs to the daughter of former South Africa President Jacob Zuma, and not his son as originally stated.