Delegitimisation of the ‘Demos gegen Rechts’ by pro-Russian and far-right actors in Germany

By: Solveig Barth, Michel Seibriger, Paula Matlach

22 March 2024

This Dispatch is also available in German.

Introduction

Germans are taking to the streets against far-right extremism and anti-democratic ambitions that have been gaining support in Germany for years. Since the research centre Correctiv published its revelations about far-right mass expulsion plans on 10 January 2024, hundreds of thousands of people have engaged in protest. However, while the Demos gegen Rechtsi are forming into an enormous pro-democracy movement that has not been seen for decades and are met with a great deal of support from both the general public and politicians across Germany, the movement also faces backlash in the form of disinformation, harmful conspiracy theories and attempts to shift the blame, fomenting in far-right chat groups and on alternative media sites.

This short qualitative analysis shows how far-right, pro-Kremlin or alternative media and chat groups on Telegram strategically spread disinformation and conspiracy theories about the Demos gegen Rechts. The following tactics were identified: Discrediting the research centre Correctiv; claiming that the demonstrations were state-orchestrated; echoing narratives of state control and an attempt to deflect blame; GDR and Nazi comparisons; conspiracy theories that the demonstrations served as a distraction from anti-government farmer protests; the claim that the Demos gegen Rechts were ineffective; and the use of ‘whataboutism’ as a diversionary tactic. Finally, the amplification of these tactics and disinformation by pro-Kremlin accounts on X (formerly Twitter) is also analysed.

Delegitimisation tactics at a glance

Discrediting Correctiv

A central component of the strategic delegitimisation of the protest movement are attempts to discredit Correctiv’s research and the journalists involved. In far-right media, the investigative media outlet’s analysis is labelled as erroneous or completely fabricated. The Correctiv editorial team is described as a “government propaganda tool” that harasses far-right groups and parties like the AfD or the WerteUnion, the newest party founded by former members of the centre-right CDU in February 2024 and whose members were also part of the meeting reported on by Correctiv. Other articles question the credibility of the Correctiv research centre as a whole, its sources in particular, and certain authors such as Jean Peters. In order to cast doubt on the accuracy of the research before the Hamburg Regional Court, official statements were used from people who, according to Correctiv, took part in the secret meeting but now deny both the meeting and the expulsion plans. These claims are conflicting the Correctiv team’s affidavit.

Image 1: Screenshot of a post by Journalistenwatch with the title “Mass demonstrations ‘against the right’: lies, trickery, and propaganda” (accessed 16/02/2024).

Another attempt to delegitimise the demonstrations is disinformation claiming that the Demos gegen Rechts are orchestrated by the state and that the photos and video footage are manipulated. An article by a far-right alternative news platform referred to allegedly manipulated photos of the demonstration in Hamburg on 19 January 2024 to support this claim. By comparing the two photos (see Image 1 above), a change of perspective creates the impression that the crowd depicted in the left photo is standing in a place where there should be a body of water. Although a fact check proved that none of the photos had been manipulated, the claim persisted and reached thousands of people via various channels and accounts on X, Facebook and Telegram.

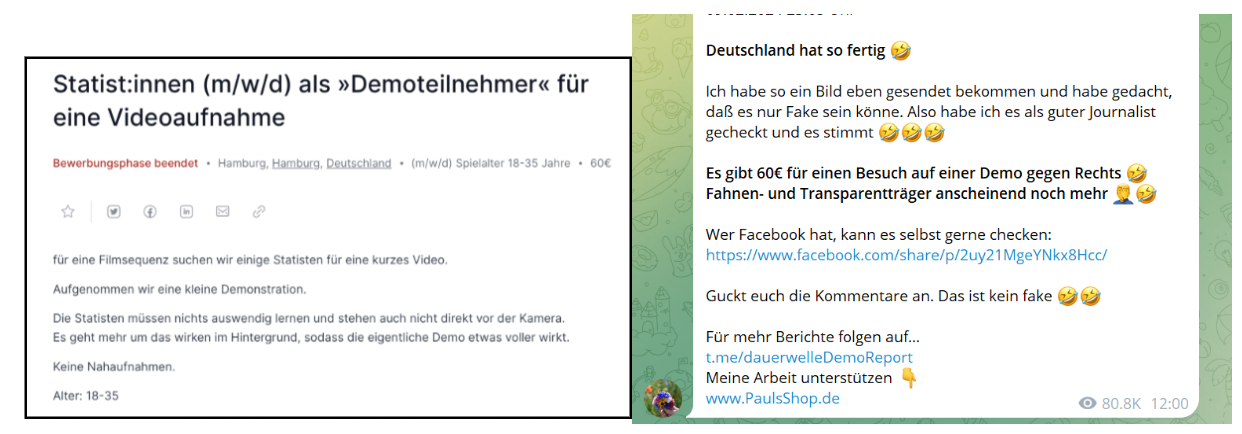

Image 2: Screenshot of a job ad posted on the portal JOBWRK that was shared by alternative news platforms and Telegram accounts in the context of the Demos gegen Rechts (left); screenshot of a Telegram post according to which protestors were paid for their attendance at the demonstrations (right) (accessed 16/02/2024).

Some posts also spread disinformation claiming that the demonstrations had been staged. For example, a post with 80,800 views (16/02/2024) from a Telegram channel that regularly promotes conspiracy theories claimed that participants had received a fee for their presence. An advert was shared on the job portal JOBWRK, which was looking for extras as “demo participants” for a video recording. A far-right medium speculated that the advert must have come from “state-affiliated media” based on the ad’s “strictly politically gendered German”. JOBWRK later clarified on its own website: “The advertisement was published on 13 October 2022, with a closing date for applications on 18 October 2022 and is in no way connected to the demonstrations in Hamburg on 19 January 2024.” Nevertheless, despite correction and clarification, this disinformation was also maintained and incorporated into the conspiracy theory of state orchestration of demonstrations.

State control and victimisation

Image 3: Screenshot of an article by “Tichys Einblick” titled “Organised demos and their impact on opinion” (accessed 16/02/2024).

Closely linked to the accusation of the demonstrations being staged is the accusation of transnational state control, which leads to alleged ‘proof’ of the supposed anti-democratic nature of the Demos gegen Rechts. Demonstrators are portrayed in far-right media as opponents of democratic diversity and are called “anti-democratic”. They are accused of using unfair methods to harass and discriminate against the opposition and attempting to silence them in the manner of a “red-green inquisition”, referring to the alleged political oppression by social-democrats, supporters of the centre-left, and Green party. In this line of argument, the AfD become the victim and the demonstrators the aggressors. As part of the victim narrative, for example, ISD analysts found claims on a far-right news platform that demonstrators are state-controlled and influenced by state propaganda, and that they sheepishly contributed to the suppression of the AfD. This claim is also seen visualised by replacing demonstrators in pictures with sheep. The apparent intent of these posts is to distract from the origin of the Demos gegen Rechts, protesting the remigration plans discussed at the conference in Potsdam and uncovered by Correctiv.

GDR and Nazi Germany comparisons

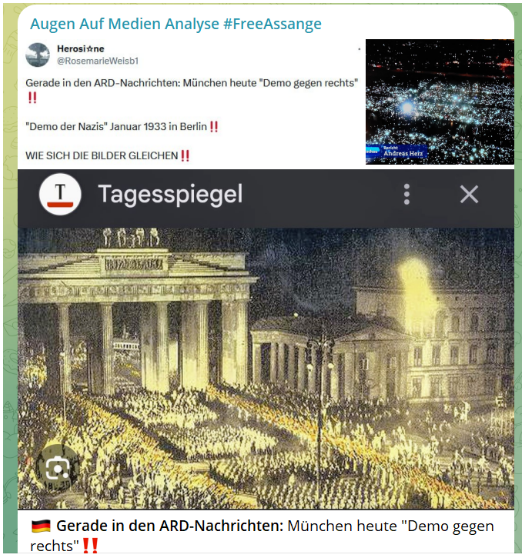

Image 4: Screenshot of a Telegram post contrasting a picture of Nazi marches in 1933 with the Demos gegen Rechts (accessed 16/02/2024).

Another regularly observed form of self-victimisation is the comparison between democrats and Nazis with the goal of causing confusion and discord among democratic actors. In the context of the Demos gegen Rechts, comparisons with the political system of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the Nazi regime were drawn in articles by far-right media with the aim of portraying the demonstrators as an oppressive mass and the AfD as the ‘oppressed opposition’. In a Telegram post by a conspiracy ideologist’s account, a comparison is made with the political persecution of the Third Reich by juxtaposing a photo of the Demos gegen Rechts with a picture of a “Nazi demonstration” from 1933 (see Image 5 above). The post was viewed 3,065 times at the time of data collection (16/02/2024).

Alternative far-right media sources also argued that people with different political views were being systematically suppressed. The accusation that “people are no longer allowed to say what they think” has a long history in mainstream discourse. Specifically, calls from employers, political representatives, or teachers to attend demonstrations were used as supposed evidence of ideological oppression and a compulsion to demonstrate. The term “involuntary voluntariness” is used to draw a comparison with a practice used in the GDR and to accuse the demonstrators of “formally voluntary” or state-orchestrated participation.

Image 5: screenshot of an article by the blogger Reitschuster titled “the end of democracy as we know it” (accessed 16/02/2024).

In addition to these distortions of history, the German government is also accused of showing parallels with contemporary autocratic states. The support of many politicians for Demos gegen Rechts is reinterpreted as supposed proof of autocratic structures as it is assumed that no democratic government would need thousands of people to demonstrate for them.

Conspiracy theories: The demonstrations are meant as a distraction

Image 6: Screenshot of an article by “Tichys Einblick” titled “Instead of changing policies, the traffic light coalition delivers marches against the middle-class protests” (accessed 16/02/2024).

The tactics and disinformation described so far are also used to corroborate conspiracy theories according to which the current coalition wants to divert attention from the farmers’ protests which were putting the government under increasing pressure in recent months. Alternative far-right news platforms claim that the government has used a “secret meeting, delivered on demand” and “imagined far-right extremist” as a pretext to distract from the protests of those “who do not shy away from their own costs and efforts, who fear for their future, who are disavowed as Nazis and subversives and still dare to take to the streets in all weathers to rebel against a maximally destructive policy”. With this tactic, the Demos gegen Rechts and farmers’ protests are played off against each other.

Another narrative is the allegedly large presence of “left-wing, radical far-left and extreme far-left groups” at the demonstrations against the far-right. The core element of this narrative is the assertion that the participants do not represent the opinion of society at large and therefore do not speak for it.

The demonstrations help the AfD

Another delegitimisation tactic used by far-right media is aimed at presenting the demonstrations as ineffective or as the cause of electoral gains for the AfD, based on an un-evidenced causal link between mass demonstrations and elections and polls. However, polls following the demonstrations showed losses of several percentage points for the AfD nationwide. Nevertheless, the AfD saw gains of over 5% in the repeated election in Berlin. Based on the election results in Berlin and a poll in Lower Saxony, ISD analysts found a Telegram post on a far-right extremist channel claiming that the demonstrations against the right were “ineffective” or even an “advertising campaign for the AfD”. For example, a post on the Telegram channel of a far-right online magazine claims that the alleged “agitation” against the AfD during the demonstrations has further strengthened the party. The gains were due to a “change of heart among the population”, according to a post on the channel of former Tagesschau news anchor Eva Hermann, which had over 30,000 views at the time the data was collected.

The demonstrations, despite their large turnout across Germany, were met with much derision from the far-right. With the repeated election in Berlin as the only state level election since the Demos gegen Rechts at the time of writing it remains to be seen whether the protest movement will translate into election results in the medium and long term.

‘Whataboutism’

In addition to delegitimisation, “whataboutism”ii was found in the form of references to apparently unrelated topics mentioned in the context of the demonstrations. iiiBy exploiting emotionally provocative pieces of (dis)information, the tactic of whataboutism is used to portray the demonstrations as irrelevant in comparison to other issues. This argument serves to distract from the content of the demonstrations or far-right extremism in general and to steer the discussion towards emotionally accessible and polarising topics. Both xenophobic and homophobic attitudes continue to be central elements of right-wing ideologies and lines of argument.

One such reference can be found in a Telegram post from a far-right channel, which had 4,683 views at the time of data collection (16/02/2024) and speculates on a supposed criminal offence (sexual assault) committed allegedly by a foreign national. The ‘whataboutism’ narrative is thus used to suggest people should be concerned about issues that are charged with xenophobic attitudes, instead of participating in demonstrations against those who are presenting as willing to care for these topics.

Amplification by pro-Kremlin accounts

Pro-Kremlin accounts in Germany also adopted most of the tactics mentioned above and spread them further. They point to the ‘favourable’ timing of the publication of the Correctiv analysis and the alleged prior knowledge of media and politicians as evidence pointing to a distraction from the farmers’ protests in Germany, as well as the attempt to pigeonhole the participants of the farmers’ protests as far-right.

The Correctiv analysis was also portrayed by pro-Kremlin channels on social media as an “orchestrated campaign” by the state and public broadcasters against the AfD. The investigative team was attacked by Russian state media, who pointed to allegedly dubious donors that “pulled the strings” behind Correctiv. For example, RT.DE, which is no longer available in Germany, shared a video on X pointing out that Correctiv was partially funded by the Open Society Foundations (OSF). OSF was founded by US philanthropist and investor George Soros, who is regularly targeted by far-right and antisemitic conspiracy theories.

Conclusion

This analysis demonstrates how the tactics of delegitimisation and self-victimisation are key elements in the interpretation of the Demos gegen Rechts by far-right actors. The aim is to cast doubt on the authenticity of Correctiv’s research and instead argue that the demonstrations were a repressive tactic directed against the AfD. At the same time, ideological elements of far-right actors, such as homophobic attitudes, are placed to redirect the discourse to other topics. Disinformation is deliberately used by both far-right and pro-Kremlin accounts to delegitimise the criticism voiced during the demonstrations against the far-right. By doing so, these tactics seek to distract from the policies of, and links between, far-right circles and the AfD as well as members of the WerteUnion.

ISD does not share primary sources of far-right, right extremist or conspiracy ideological origin. These are available on request.