Fake ‘Freedom Convoy’ Facebook Groups are being run by Foreign Networks for Profit

24th February 2022

By Elise Thomas

As so-called ‘Freedom Convoy’ protests take off in multiple countries around the world, a similar pattern is emerging. In the United States, Canada and Australia, social media groups claiming to be part of the protest movement are being exposed as being run from foreign nations.

This is not an elaborate attempt at state-linked foreign influence. This is the conspiracy clickbait industry at work.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Earlier this year, ISD published a series of investigations into how inauthentic networks linked to Vietnam were promoting QAnon and other conspiracy theories in order to generate a profit. The three case studies examined different business models the network operators were using, alongside the use of fake and hacked accounts and techniques to circumvent content moderation on social media platforms.

While the series focused on networks in Vietnam, the goal was to illustrate a larger point: commercial influence operations can be equally or more impactful than state-linked operations and, as an industry, operate at a much greater scale. Their motivation may be commercial, but their effect is political and social.

This is precisely what appears to be happening with the convoy protests.

Fake groups are targeting US & Australian users

Journalists and researchers have found dozens of supposed ‘Freedom Convoy’ Facebook groups targeting North American or Australian users. These groups are linked to content mills or commercial operations in Vietnam, Bangladesh, India and other foreign countries. Many of them are making use of hacked or fake accounts, as well as other techniques also used by the networks profiled in our earlier Conspiracy Clickbait series.

Facebook announced on 7 February that it had removed a number of these “spammers and scammers” targeting the Canadian convoy, but as of 16 February it was clear that there are many such groups still in operation.

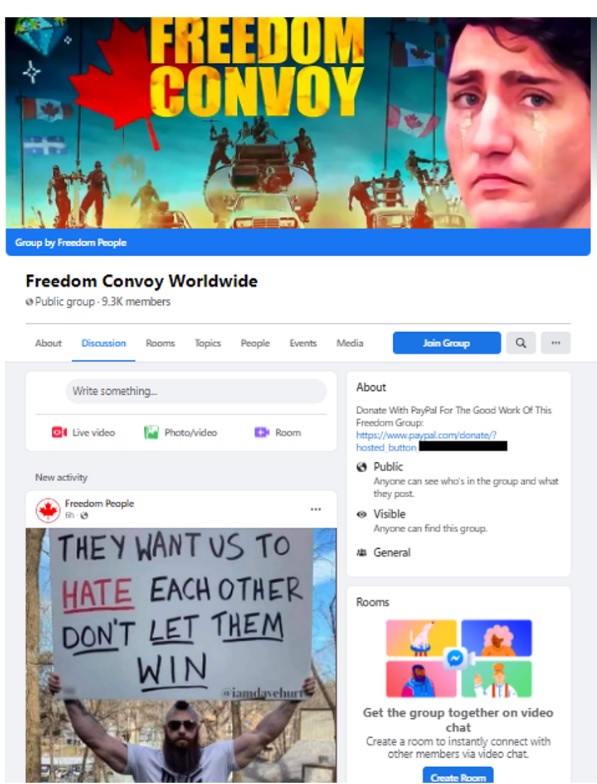

To pick just one example, on 16 February the group ‘Freedom Convoy Worldwide’ had 9,259 members5,411 of whom had joined in the previous week. The group was active, full of what appear to be real Canadian users posting content relating to the protests in Ottawa. It was also soliciting donations directly to a Paypal account.

The inauthentic ‘Freedom Convoy Worldwide’ Facebook group solicits donations via Paypal.

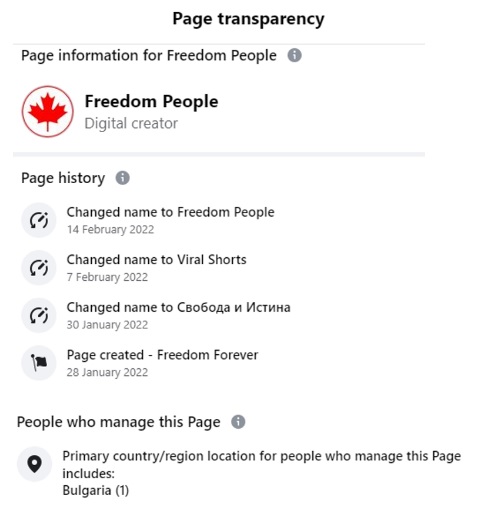

However, a brief inspection of the ‘Freedom People’ page, which ran the Facebook group, revealed that it had changed its name multiple times and was being run from Bulgaria.

Page transparency details for the page ‘Freedom People’, which runs the ‘Freedom Convoy Worldwide’ Facebook group.

The group was mentioned in an article published in The Verge on 19 February, and appears to have been removed as of 21 February.

For the Bulgarian operator, the motivation for running this group was likely financial. The effects of anti-government groups like this, though, are not dictated by their administrators’ motives (except that supporters’ donations are likely being stolen).

For the real Canadian Facebook users in the group, it is a source of distorted and divisive political content, a place to share conspiracy theories and anti-vaccine misinformation and ultimately fan the flames of the protests that have paralysed parts of Ottawa for weeks. As in our Conspiracy Clickbait series, the operator is capitalising on polarisation and division for commercial ends.

Why does the conspiracy clickbait industry pose a threat?

The key point surfaced by the Conspiracy Clickbait series is that the real threat does not come from any single commercial network. The real threat is the development of a dispersed global industry around this kind of content. This is a concern for two main reasons: scale and opportunism.

The problem with scale is fairly straightforward. If you have one Facebook group managed from Bulgaria reaching 9,200 people in Canada and the US, the impact is not significant and can be moderated relatively easily by social media platforms. If you have five hundred, or a thousand groups managed from all over the world, each reaching 9,200 people (and in many cases a lot more), the impact could be very substantial. The sheer number and diversity of operators also make it more complex to detect and remove.

The problem with opportunism is that commercial networks are content agnostic. They will jump on any topic or issue that appears to be gaining traction and driving clicks. In practice, this means that they are likely to attach themselves to largely organic movements such as the convoy protests, and amplify and escalate those movements. Then, when that movement dies down and the next one comes along, they will quickly switch over and do it all again.

The implication of this is that there is likely to be an increasingly systemic problem in which divisive social movements and issues are inauthentically marketed to domestic audiences by foreign networks looking to make money.

The events of the past several weeks are a powerful illustration of why a narrow focus on state-linked influence operations risks missing the woods for the trees. State-linked influence operations are important to identify and understand, but they are also rare and often have relatively little direct impact. By contrast, commercial influence operations are increasingly ubiquitous and arguably have a stronger direct incentive to make sure their content is reaching their audiences. It is far past time we gave the risk posed by this industry our collective attention.

Elise Thomas is an OSINT Analyst at ISD. She has previously worked for the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, and has written for Foreign Policy, The Daily Beast, Wired and others.