Extreme Dialogue: Former conspiracist shares story to help others understand the realities of extremism

By: Hugo Besançon and Krystalle Pinilla

21 December 2022

Sylvain is a former conspiracist.

He believed the government and a group of ‘elites’ were operating against him and fellow members of society. They were the reason he couldn’t afford to feed his daughter and the ones to blame for his problems.

Today, at the age of 52, he works as a consultant in management and financial crime prevention in Montreal and hopes to help people steer away from conspiratorial thinking by sharing his story with Extreme Dialogue, ISD’s longest-running educational programme for confronting the realities of extremism and hate. But this wasn’t always the case for Sylvain.

Growing up, he was picked on for being too tall. He recalls one time sitting in the locker room after a gym class and getting attacked by fellow classmates.

“They took away my clothes, they humiliated me and they spat on me,” he said in his native French. “That was really hard to live with. I felt all alone.”

Getting beat up during school hours caused him distress. “I didn’t understand why my friends and the other kids had so much violence towards me. I hadn’t done anything to them. I just wanted to be. I just wanted to live.”

It was the beginning of a series of grievances that would put him in the crosshairs of a conspiracy movement later in life. After having his bank accounts blocked during a misunderstanding with the government about a company entity he set up as a now adult, he was unable to feed his daughter who had “serious health problems.”

“I was very angry.”

A co-worker approached him. “He said, ‘listen, if you’re interested, I could invite you to an evening. There are people there who can educate you. They can tell you the truth about what the government hides from us’. And so of course, because I was in a vulnerable state and I was angry, I went to this evening.”

Sylvain became fixated on ‘the real banking system’ and met a friend who said he hadn’t paid taxes in 20 years but still owned a house. “I said to myself, there’s people here who know something that I don’t.”

He proceeded to immerse himself in online networks to try to understand it all. Soon, he found himself spiralling through more and more conspiracies and joining the “Freemen of the Land” movement. Similar to ‘Sovereign Citizens,’ Sylvain believed the government and elite wanted him to be a slave for their benefit. Worse, they weren’t telling him and society that the world was going to end on 12 December 2012, as prophesised in the Mayan calendar.

Sylvain believed he and his fellow conspiracists were the only ones who “knew the truth.” He ended up selling his home, leaving his job and moving to a town called Rawdon (Quebec) at 600-feet above sea level. It was the only way to survive.

“My goal was to accumulate the maximum amount of food, of weapons, to be able to protect myself, to have a generator, to become independent and disconnect from the electricity grid.”

But the day never came. Weeks passed and he began to question everything. He tried to rebuild himself, but then his new company was targeted by an organised crime group, he said. He felt paranoid, as if he was being watched. But right before he could give up, a client who was a cybersecurity specialist offered to help. She blocked the hackers and removed their access.

It was then that Sylvain felt he could finally consider leaving the movement, freeing himself from those he paid to teach him about the banking system and leave society. He decided to help others trapped under the same profiters and so-called gurus working in the movement. “I wanted to help others wake up, so they didn’t follow the same path as I did.”

Sylvain shares his story as one of two accounts featured in Extreme Dialogue’s re-launch in Canada. After a hiatus since before the pandemic, the programme is once against releasing short films and educational resources offering an insider’s perspective on the consequences of these movements, while challenging stereotypes about the profiles of those who become involved.

Supported by Public Safety Canada, Extreme Dialogue partnered with Duckrabbit, The Tim Parry Johnathan Ball Peace Foundation, and the Montreal Centre for the Prevention of Radicalization Leading to Violence (CPRLV), to create these resources. The resources are now being deployed to different schools across Quebec.

What is Extreme Dialogue?

Extreme Dialogue is a series of multilingual, interactive resources for teachers, youth workers and others engaging with young people, centred around the first-hand stories of former extremists and survivors of extremism.

It is ISD’s longest-running education programme to date, reaching thousands of practitioners in Canada, the UK, Germany and Hungary since 2015.

Extreme Dialogue operates with one central idea in mind: building empathy and understanding for different life journeys, including the pathways that can lead to violent and extremist behaviours. It explores the stories of those affected by this ideology and sometimes violence, and offers a safe, constructive space to discuss complex topics around belonging, identity, fear, responsibility and empathy.

Previously, we have spotlighted multiple stories, including:

- a former member of the extreme far-right in Canada,

- a mother from Calgary whose son was killed fighting for ISIS in Syria,

- a youth worker and former refugee from Somalia,

- a former member of the Irish Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) whose father was killed by the IRA,

- a former member of the (now-proscribed) UK Islamist group al-Muhajiroun,

- a Syrian refugee living in Berlin,

- a member of the Roma community in Hungary targeted by far-right demonstrations.

By profiling situations and testimonies from different genders, ages, ethnicities and contexts, Extreme Dialogue has allowed participants to unpack the multifaceted aspects of extremism and its impacts. These resources are meant to fight against any form of “us versus them” thinking and challenge attitudes that advocate for or incite violence – this is especially important in light of new ways for interacting, finding information and forming community in the digital space. We know that young people are regularly exposed to hateful and dangerous content both on- and offline, yet often lack the vocabulary or proper structure to discuss what they’ve encountered. Extreme Dialogue aims to provide them (as well as their mentors and caregivers) with a platform to explore these more ‘taboo’ topics in a structured, positive way.

The films are a pivotal piece of this puzzle, offering an insider’s perspective on extremism and humanising issues through real-life experience. In the fight against radicalisation, it is vital to understand the grievances and factors which can drive individuals both into and out of extremist movements, or push them toward violence. It is also crucial to understand the pain that victims and survivors experience, and to explore how traumatic events in an individual’s life can catalyse their own descent into violence or hate.

The programme resources available online include a learning package: a Prezi presentation, a facilitator guide (explaining the The Tim Parry Johnathan Ball Peace Foundation’s approach to facilitating Extreme Dialogue), an educational resource and interview clips focusing on specific topics or concepts directly tied to the story at hand. The resources come together to create an open and active classroom environment, based on experiential learning. They are structured in a way that seek to enhance the learning experience of the viewing audience.

Extreme Dialogue Canada

After a 4-year hiatus, Extreme Dialogue is back with two new resources that are already being deployed across schools in Quebec.

The French-language films and educational resources focus on the Canadian context and include English translations.

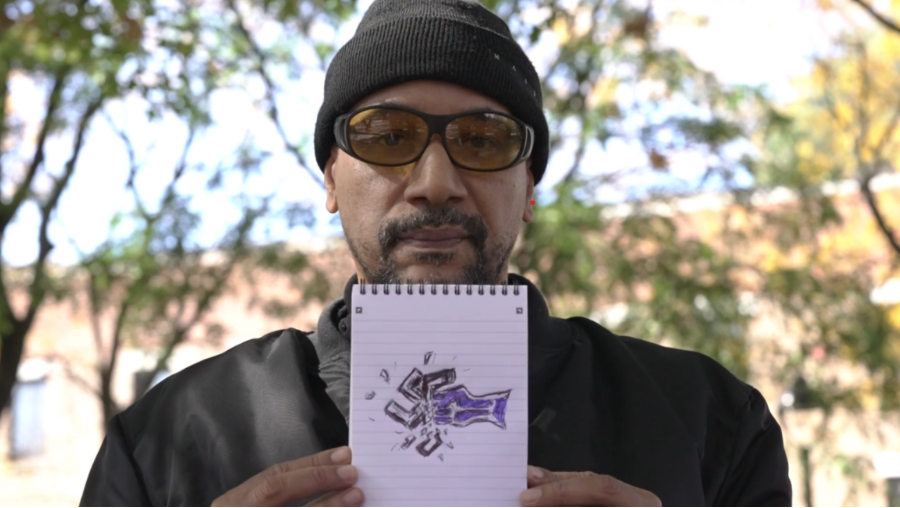

Along Sylvain’s account, a second film tells the story of Junior. In the 1990’s, Junior participated in the creation of the Montreal Antifascist League (L.A.M), a youth-led group formed as a direct response to violent far-right attacks in the region. As L.A.M’s spokesperson, Junior soon realised they could fight back against neo-Nazis that were targeting civilians at concerts, but some of the most effective tactics began to bring troubling scenarios in the longer run. His testimony reflects on those days, the choices they made, and what he would do differently now. His story challenges how we stand up for personal causes, even those defending justice and equality, but shouldn’t lose sight of our core values. It also challenges viewers to consider the methods used to fight for peace, and how change can be achieved collectively in the face of violence.

Conclusion

We believe that dialogue is a key component in drawing people away from extremism and intervening or disrupting the radicalisation process. The desire to counter or discuss with those we disagree with, or are different from, can be overwhelming. However, these conversations can sometimes entrench and alienate, making it harder to achieve our goal to engage and connect. Similar to the “Freemen of the Land” movement, we’ve seen ‘Sovereign Citizens’ and, more recently, Reichsbürger adherents justify violence or plots for violence as an act against what they consider an ‘illegitimate’ government. Equipping young people to understand how to confront this kind of ideology with real-world examples is one of the best tools for anyone joining a democratic society.

The resources ultimately create space where participants can encounter ‘the other’, think critically and engage in meaningful dialogue, both through the films and in real life. They do not intend to “teach” something, but to provide opportunities for engagement, empowering participants to feel listened to, involved and validated.

We realise extremism is a highly complex subject. Those who work or live with young people have told us that they can be nervous about approaching issues around hate or extremism and don’t always feel sufficiently equipped or confident to hold the conversation. We want to equip them with absolute confidence and a means of answering difficult questions through a series of structured, versatile, active and reactive educational resources. Extreme Dialogue provides a structured framework that suits different groups, objectives and sensitivities.

Schools and other practitioners can contact us to request Extreme Dialogue training workshops and in-classroom session delivery to young people in schools and community settings.