Memes & the Extreme Right-Wing

A downloadable version of this page can be accessed here.

What are Internet Memes?

An internet meme is “a piece of culture, typically a joke, which gains influence through online transmission”. Internet memes are considered a part of Internet culture and are visual tropes that most often take the form of an image-text combination. Simple to understand and usually a comedic appropriation of broader culture, they can be “mimicked or remixed” (replicated or altered) by any online user. The speed at which memes can gain popularity through widespread distribution on the internet has led to them becoming a type of “viral phenomena”.

Internet Memes & the ‘Alt-Right’

The emergence and growth of the “alt right” (“alternative right”) movement in the early 2010s was characterized by an extensive use of social media and online memes. A particularly important moment in the formation of the alt-right was during the 2016 US presidential campaign, where the memes that they produced and disseminated online flooded the internet with pro-Trump content to such an extent that it was dubbed a ‘meme war’, and is considered to have been instrumental in shifting the public narrative to one that was sympathetic of Trump.

The alt-right’s use of memes is thought to have “established a cultural policy that combined ideas of white supremacy with digital meme, game and hacker cultures in such a way that it provided fascist ideology with a new look or image…for the digital age”. Memes have since become a central online communication, propagandizing and recruitment tool for the extreme right.

The Visual Culture of Memes

The visual aesthetic and functionality of memes as a form of communication has been used strategically by the extreme right. Extreme right-wing movements have used memes to condense complex, radical ideologies into a more appealing and ‘palatable’ format that can be disseminated effectively online, reaching broader audiences on mainstream platforms.

Through using humour and irony to obfuscate extremist narratives, it has been suggested that memes “lower the barrier for participation in extreme ideologies”, especially amongst younger audiences. Researchers have suggested that extreme-right memes may influence radicalization trajectories into violence, whereby prolonged exposure to the trivialization of hateful, violent, or racist beliefs can lead individuals to normalize the content and become gradually more tolerant of violent extremist ideologies. Scholars have also noted that as users become more embedded within extreme communities online, they may also be exposed to “shock memes”, which can feature graphic violence and potentially erode psychological barriers to violence.

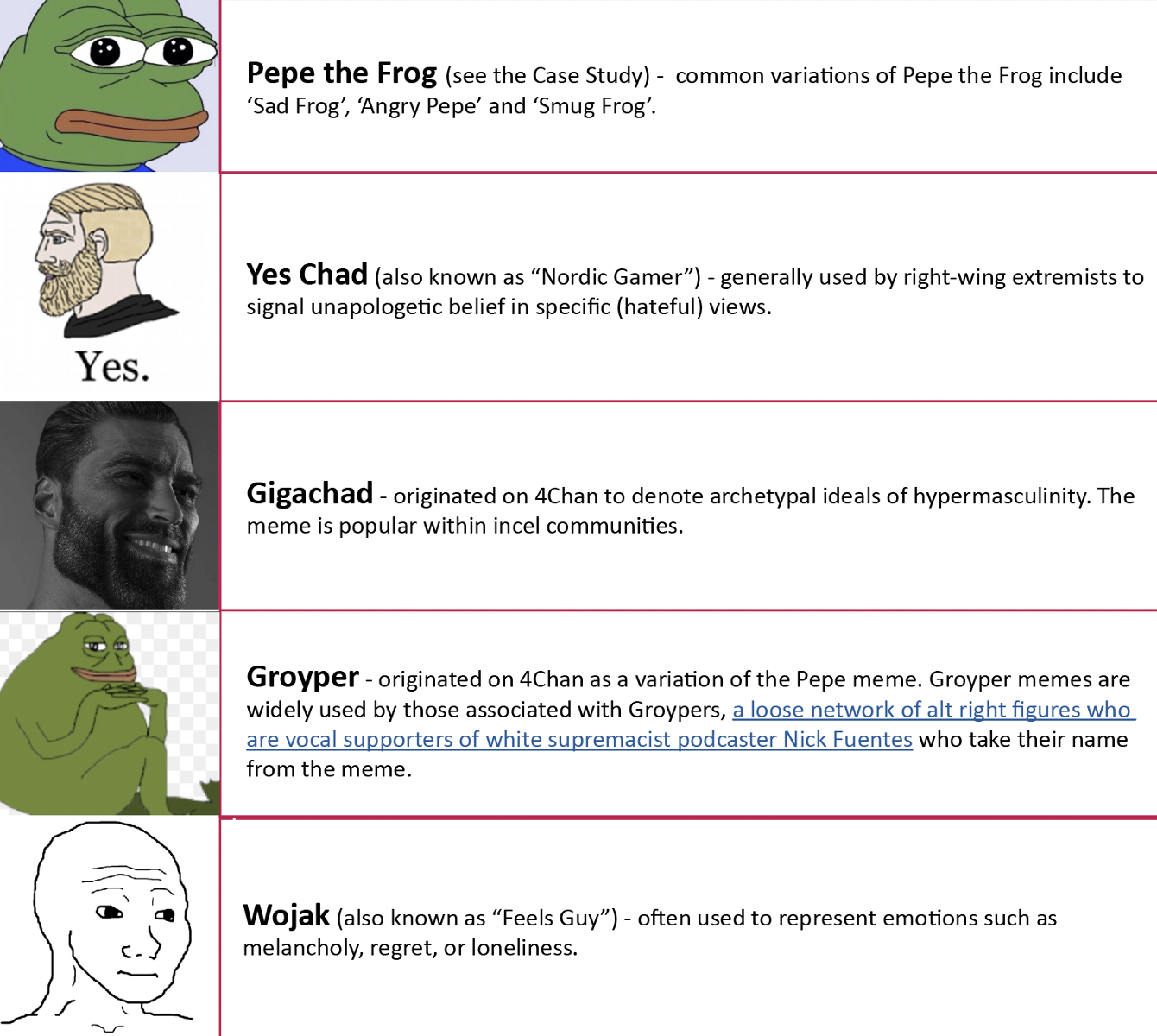

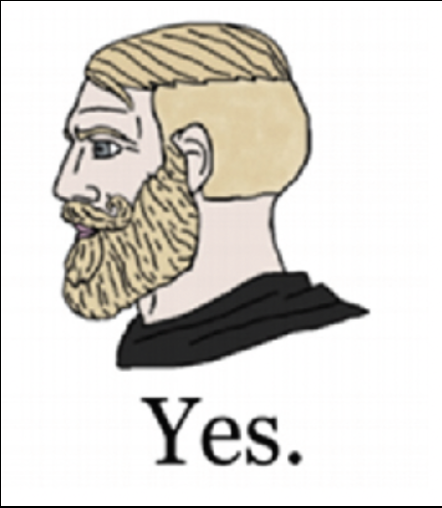

As memes convey meaning through association rather than explicit argument, not all extreme-right memes are clearly violent, hateful, or racist. Rather, they can take on these connotations when situated in a wider extremist context, only recognizable to someone embedded within that context. An example of this is the ‘Yes Chad’ meme: to the unfamiliar observer the image appears entirely innocuous, and it is often used on social media without any hateful or racist connotations. On 4chan, however, a study highlighted that the ‘Yes Chad’ meme is “often used as the archetypical (white) face of /pol/ culture, with the blunt ‘yes’ caption often being used to succinctly undermine ‘leftist’ politics or to frankly affirm racist statements”.

‘Yes Chad’ meme

The “Overton Window” refers to the range of policy ideas that society accepts as legitimate options. This range is not fixed but rather shifts as societal values and norms evolve. Some scholars have suggested that the extreme right-wing’s use of memes to disguise hateful or extreme messaging with humour and irony is a tactic to shift the Overton Window. In this way, by progressively exposing users to increasingly malign content concealed as ironic parody, extreme right-wing ideologies slowly become a part of the broader social consciousness. This dynamic can be observed in the “red-pilling” Discord logs collected by Unicorn Riot after the fatal ‘Unite the Right’ rally in Charlottesville in 2017, where one user comments that he became involved in antisemitism “as a meme first off…. then all of a sudden it stopped being a meme”.

Sample Discord logs collected by Unicorn Riot

Case Study: Pepe the Frog

Perhaps the most well-known meme associated with right-wing extremism is Pepe the Frog. As a case study, Pepe the Frog shows how extreme-right memes can be existing, everyday images co-opted from non-extreme contexts and infused with extremist narratives. The evolution of Pepe the Frog not only points to how online memes grow and evolve through user participation, but also shows how white nationalist beliefs were pushed into a very mainstream position using a popular meme.

A cartoon frog from the 2005 online comic series ‘Boy’s Club’, Pepe the Frog is not inherently racist or hateful but rather “a chill frog”, according to its creator. The Pepe meme originated on 4chan in 2008 and was initially used by a handful of small online communities on the platform. Due to the versatility of the frog image, Pepe memes increased in popularity and spread into the mainstream over the following years. The image was endlessly repurposed – there was “Batman Pepe, Supermarket Checkout Girl Pepe, Borat Pepe, Keith Haring Pepe and even carved Pepe pumpkins” – and it was even used by celebrities such as Katy Perry and Nicki Minaj. In late 2014, the emergent ‘alt-right’ decided to begin a “campaign to reclaim Pepe from normies”, or mainstream members of society. Pepe memes conveying white supremacist themes – such as Pepe dressed as a Nazi; making racist or antisemitic comments; or depicted as Hitler – subsequently began to increasingly appear online.

The original ‘feels good man’ Pepe the Frog meme.

By 2015, Pepe the Frog had become well established as a white nationalist icon and symbol of the ‘alt-right’ movement in the US. Simultaneously, the Pepe image was also affiliated with supporters of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign due to the creation and dissemination of memes combining Pepe the Frog with Donald Trump. The affiliation between Pepe and the Trump campaign was cemented when Trump retweeted a Pepe meme of himself, bringing the image – and its extreme right-wing connotations – into mainstream political discourse. Pepe’s symbolism in this regard was given validity in 2016, when Hilary Clinton’s campaign posted an ‘explainer’ of image, publicly denoting it “a symbol associated with white supremacy”.

(Left) Donald Trump’s retweet of the Pepe/Trump meme; (right) extreme right-wing memes of Pepe the Frog.

Strengthening Community

The centrality of memes in extreme right-wing culture rests in the conveyance of meaning through association rather than explicit argument, whereby familiarity is required to understand a meme’s specific message in a given context.

In this way, memes can help cultivate a sense of collective belonging, and an “imagined community”, amongst individuals participating in otherwise dispersed online networks. A result of this is that supposedly humorous and harmless images in the cultural space can begin to shape an individual’s political worldview and opinions.

The participatory culture of memes reinforces this: as users become more active in the reproduction and continuation of in-jokes through editing existing memes, they also become bound by dynamics of co-production as well as consumption. It has been noted that this contributes to the creation of an ‘in-group’ status, which is critical in fostering an extremist mindset and has played a particularly influential role in instances of radicalization into lone-actor terrorism.

Meme ‘Terrorism’

Prior to the terror attacks on two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand in March 2019, the attacker posted his manifesto to the ‘/pol/’ (politically incorrect) board on 8chan. The manifesto was filled with memes and in-jokes, familiar only to the online community that it was posted to, thus signalling solidarity to the ‘in-group’ who understood it while simultaneously excluding those that did not. The attacker called upon others to “create memes, post memes, and spread memes. Memes have done more for the ethnonationalist movement than any manifesto.” It was reported that the “8Chan community responded with a wave of visual memes glorifying violence, mocking the victims once again and celebrating the assassin as a saint”.

Following the Christchurch attack, four more ‘copycat’ right-wing extremist terror attacks occurred in 2019 in Poway, California; El Paso, Texas; Bærum, Norway; and Halle, Germany; each committed by lone actor terrorists. Like the Christchurch attacker, each uploaded a manifesto prior to their attack that placed racist and extreme beliefs into memes. The inclusion of memes in the writings of lone-actor terrorists indicates the importance they play in extreme right-wing communities online and why they should not be overlooked as an inconsequential form of communication. The communicative power of memes in helping to facilitate the transition from online activities to offline violence and terrorism can be gleaned from the following examples.

The meme, “The Chad Saint Brenton and his loyal Chad disciples John and Patrick” was shared by the Norway perpetrator prior to his attack in 2019. An article from OpenDemocracy highlights how the image celebrates the acts of terrorism committed in Christchurch, Poway, and El Paso by presenting the attackers as “Saints”, depicting them as big-jawed, muscular and physically strong men in the visual style of the “Chad” memes found in Incel culture and ultimately glorifying their violence as “a sanctification of their inherent masculinity”. The article points toward another meme that makes this visual argument, equating mass violence towards minority communities with masculinity through contrasting the 2014 Isla Vista attacker (who was one of the first mass shooters known to be inspired by Incel ideology) with the Christchurch attacker.

The framing of physical violence as a sign of “real masculinity” and something inherently thrilling or to be celebrated has also helped radicalize individuals to far-right movements. For example, a study highlighted how memes disseminated by the Proud Boys, which embody an ideology consisting of symbolic and physical violence particularly attractive to young men in the West, aided its online recruitment efforts.

Meme comparing the perpetrator of the 2014 Incel-affiliated mass shooting in Isla Vista, California with the perpetrator of the Christchurch terror attacks.

The “Virgin vs. Chad” meme has also been used by both Islamist and right-wing extremists to celebrate the Taliban’s (or “Chad-i-ban”) recent successes in Afghanistan as opposed to ISIS’s territorial decline since 2017.

Examples

This page lists some of the common memes which are currently popular among extreme right-wing communities. It is important to note that many of these memes are not only used by extremists, but also used in other areas of internet culture. In many cases, these memes will be appropriated by extremists to express a certain belief or relay specific hateful tropes.

Further Reading

Sharing the hate? Memes and transnationality in the far right’s digital visual culture – Jordan McSwiney

The Visual Culture of Far-Right Terrorism – Lisa Bogerts and Maik Fielitz

Manifesto memes: the radical right’s new dangerous visual rhetorics – Ashley Mattheis

What Makes a Symbol Far Right? Co-opted and Missed Meanings in Far-Right Iconography – Cynthia Miller-Idriss

“Do You Want Meme War?” Understanding the Visual Memes of the German Far Right – Lisa Bogerts, Maik Fielitz

The “Great Meme War:” the Alt-Right and its Multifarious Enemies – Maxime Dafaure

World War Meme – Ben Schreckinger

Memetic Irony and the Promotion of Violence within Chan Cultures – Blyth Crawford, Florence Keen, Guillermo Suarez de-Tangil

How the Christchurch shooter used memes to spread hate – Aja Romano

From Memes to Race War – How Extremists use Popular Culture to Lure Recruits – Marc Fisher

Memes and the Moroccan Far-Right – Cristina Moreno-Almeida, Paolo Gerbaudo

_________________________________________________________________________________

This Explainer was uploaded on 23 February 2023.