ISD’s Digital Investigation on Syria Disinformation

13 July 2022

Prepared for The Syria Campaign report ‘Deadly Disinformation’.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

Earlier this year, The Syria Campaign commissioned the Institute for Strategic Dialogue to conduct a digital investigation and a series of semi-structured interviews to help examine the extent of English-language disinformation about the Syrian conflict from 2015-2021. This analysis formed the basis of The Syria Campaign’s recently published report, Deadly Disinformation: How Online Conspiracies About Syria Cause Real-World Harm.

This Dispatch unpacks the methodology ISD employed for The Syria Campaign’s report and outlines our key research findings. It aims to serve researchers, journalists, policymakers and the general public through explaining how ISD conducted this investigation and arrived at our main findings.

ISD’s online analysis examined the types of narratives and targets of disinformation, and how both evolved over the span of seven years. Our research found that the online activity of a relatively small number of disinformation actors has had a negative offline impact on those targeted by disinformation. Additionally, the policymakers we interviewed – all of whom were at some point privy to their government’s policy discussions on Syria – shared their opinion that disinformation spread by both individuals and states sometimes impacted the discussions of their respective governments.

Notes:

ISD defines disinformation as “false, misleading or manipulated content presented as fact, that is intended to deceive or harm.” ISD defines misinformation as “false, misleading or manipulated content presented as fact, irrespective of an intent to deceive.”

‘Disinformation’ and ‘Misinformation’ are examples of ‘online manipulation’ which encompasses one or more of the following:

-False or misleading information

-False identities: ‘Inauthenticity’ (bots, cyborgs, sockpuppets)

-False or deceptive behaviours: ‘coordination’

English-language disinformation directed against humanitarian actors and human rights defenders was by far most prevalent on Twitter, with less of this content identified on Facebook and Instagram. As a result, the analysis presented below will focus on Twitter data.

Methodology

Step One:

In consultation with The Syria Campaign (TSC), we created three lists as a starting point for our digital investigation. The first list contained actors, outlets and organisations who had been identified as spreading disinformation about the Syria conflict, either by ISD, TSC or existing open-source research. Within this list, ISD found that 28 actors had active Twitter accounts and 15 had active (public) Facebook accounts. The second and third lists were keywords and names developed and gathered by our research team which were/are associated with or targeted by disinformation.

In order to restrict focus to disinformation only, we tested the keyword list and used it to filter content from the 28 actors previously identified. An important limitation of any keyword-based approach is that there may be some posts that use these keywords but do not contain disinformation. Likewise, there may be posts containing disinformation that did not use any of our selected search terms. Given these limitations, we tested and refined our keyword list multiple times to maximise both recall (obtaining enough relevant posts) and precision (the posts identified contain disinformation about Syria).

Step Two:

Our research team used Brandwatch, a social media monitoring tool, and CrowdTangle, a Meta-owned public insights tool, to analyse social media content posted by these actors between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2021. In order to restrict our focus to content posted by the 28 actors that spread disinformation over the time span identified, our team filtered search results using the keyword list to only posts containing one or more of those keywords. In total, out of ~900,000 tweets from the 28 actors we monitored, we identified ~47,000 tweets containing one of more disinformation keywords, as well as 817 Facebook posts . On Twitter, ~19,000 original posts from the 28 actors spreading disinformation on the conflict in Syria have been retweeted ~671,000 times (a factor of 36x). ISD then used our quantitative findings to identify the key narratives spread by the 28 actors.

Prominent disinformation narratives

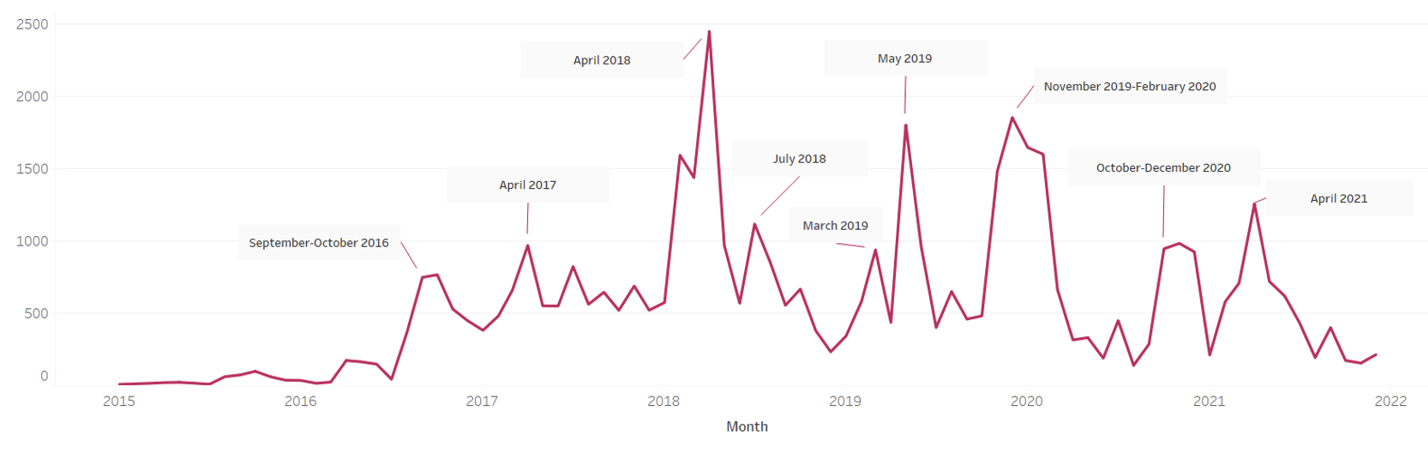

This digital investigation set out to better understand the nature of disinformation around the Syrian conflict during the period of analysis (2015-2021) . Over this period, we saw there were peaks and troughs of activity.

Image 1: The volume of Twitter posts over time. A more detailed version of this timeline can be viewed in The Syria Campaign’s full report.

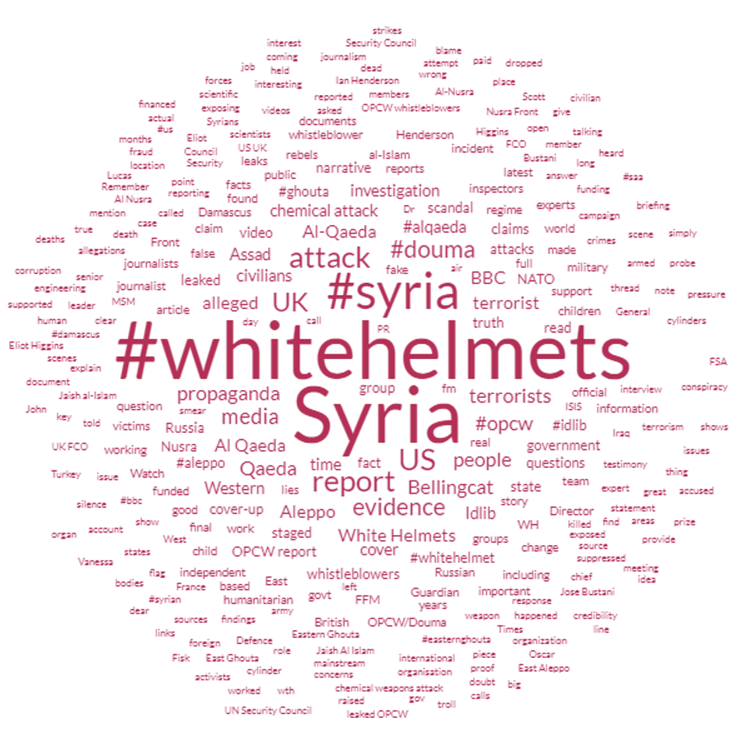

ISD analyzed the nature of the content spread by the 28 actors over time. Using Brandwatch, we created a word cloud to display the most frequently appearing terms and hashtags among all Twitter posts in the dataset.

Image 2: A word cloud displaying the most frequently appearing terms and hashtags among all Twitter posts in the dataset.

This word cloud shows that the White Helmets, a Syrian humanitarian organization famous for rescuing victims of air strikes in Syria, was the most discussed topic in the data set. It appeared almost as frequently as the word Syria itself.

Our research team then grouped prominent keywords into subsets of words that shared topical similarities. Then, we searched for further keyword co-occurrences and enlarged the list of relevant keywords for each subset. Finally, we tested the keyword lists by manually reviewing a sample of posts to ensure that each subset recalled posts that actually discussed that topic.

In total, our analysis found that three topics emerged as the principal subjects of disinformation:

- False claims about the work of the White Helmets to save lives in Syria (21K tweets);

- Denials or distortions of facts about the Syrian regime’s use of chemical weapons (19K tweets); and

- Denials and distortions of the findings of reports by the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) on Syria (17K tweets).

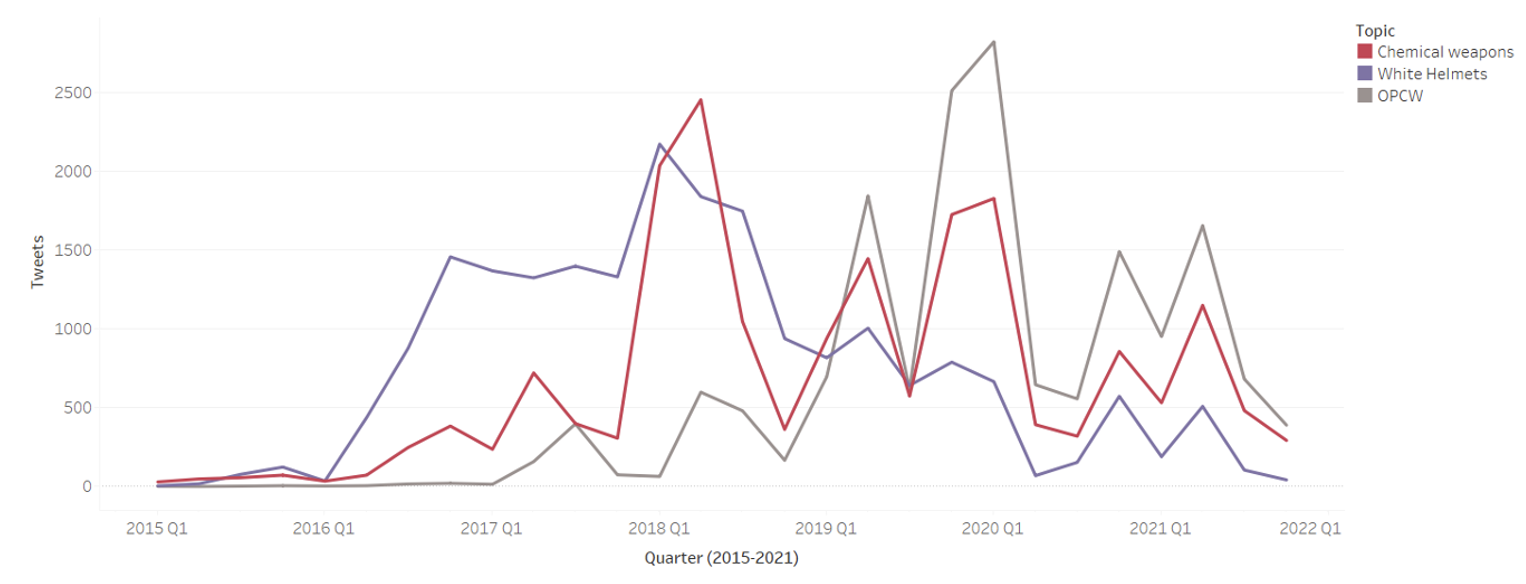

The chart below shows the evolution of these topics over time.

Image 3: Volume over time graph of tweets mentioning ‘Chemical weapons’, ‘White helmets’ and ‘OPCW’.

While the White Helmets were the most relevant topic until late 2017, the Douma chemical attacks in 2018 shifted the focus of the conversation toward chemical weapons.

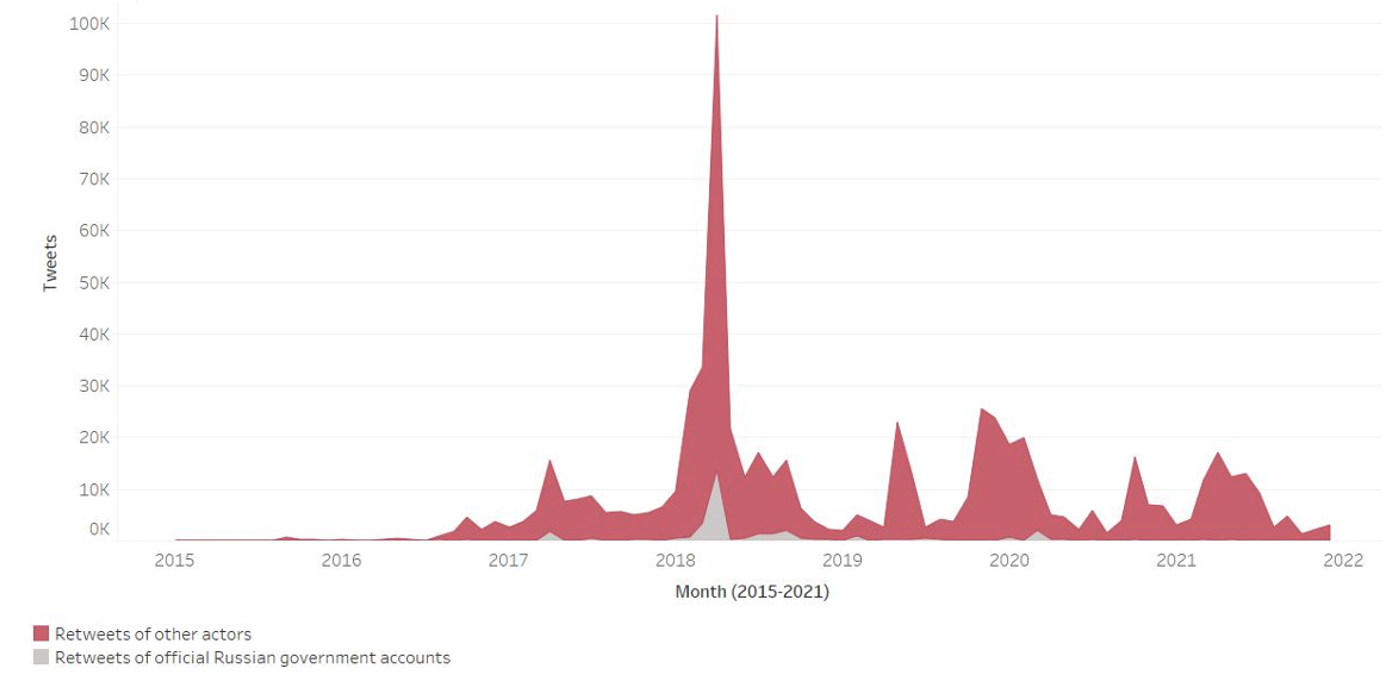

Three official Russian government accounts were included among the 28 accounts investigated for this project. These three accounts were found to be responsible for 5% of the overall disinformation spread over our examined time period. Their activity was particularly prolific around the Douma chemical attacks in April 2018. During this period, 13% of all retweets in our Twitter data set originated from those three Russian government accounts. This indicates that during a time when the international community was paying particularly close attention to potential violations of international law in Syria, Russian government accounts took on an outsized role in spreading disinformation and confusing public debate around events on the ground.

Image 4: Volume over time graph of retweets of disinformation by Russian state and non-Russian state actors.

The impact of disinformation on people and policies

Alongside our digital investigation, and in addition to interviews conducted by The Syria Campaign, ISD conducted interviews with a number of current and former Western policymakers. These policymakers were identified based on their proximity to, or involvement in, their governments’ policy discussions around Syria. ISD also interviewed several targets of disinformation.

Our goal in conducting these interviews was to understand the impact of online disinformation in the offline world, both as it pertains to Western policy on Syria and to the wellbeing of journalists and human rights defenders working on Syria. In total, ISD conducted 16 interviews with policymakers and targets of disinformation, with each interview ranging from 30 minutes to 1.5 hours.

Interviews with policymakers were semi-structured. Interviewees were given the opportunity to discuss their thoughts on the impact of disinformation in policy spaces, and most interviewees addressed one or more of the following themes:

- The prominence of disinformation in policy conversations on Syria (including online and offline false claims circulating about events on the ground);

- The extent to which disinformation shaped or impacted policy discussions regarding Syria, either in government or multilateral spaces;

- Possible solutions to the problem of disinformation; and

- Similarities between state-backed disinformation campaigns in Syria and those ongoing in Ukraine.

According to the policymakers that we interviewed, disinformation around the Syria conflict —from the nature of the opposition to the origins of chemical attacks — created an atmosphere of doubt and opacity which permeated policy discussions on Syria. According to one former US policymaker, it also “aided and abetted a culture of risk aversion.” Several policymakers provided examples of disinformation impacting policy discussions on specific topics, such as those about the nature of the Syrian opposition, or diplomatic engagements regarding sensitive issues such as refugee returns to Syria. For example, two policymakers expressed their belief that disinformation was being instrumentalized by the Syrian regime and its allies to accuse Western countries of preventing refugees from going home. This, in turn, impacted diplomatic engagements with Western allies and partners.

Conclusion

Based on our investigation, we determined that a small group of dedicated actors were responsible for the spread of a large amount of online disinformation around Syria. Spikes in volume over time indicated a focused spread of disinformation around key events in the conflict.

In addition to our digital analysis, our interview findings demonstrated that the disinformation spread by this small group of actors had offline impact and caused harm outside of online spaces. Policymakers that we interviewed explained that, while they were aware of disinformation being spread and avoided making policy decisions based on incorrect or unverified content spread online, the existence of this content still had detrimental effects on policy and practise, costing in both time and resources. Finally, interviews with targets of disinformation revealed a negative impact, sometimes severe, on their safety and wellbeing.

You can read more about these findings in The Syria Campaign’s full report, Deadly Disinformation: How Online Conspiracies About Syria Cause Real-World Harm.