Facebook’s News Ban and Its Effect on Online Conspiracy Communities

25th February 2021

By Elise Thomas

On Thursday 18 February, during the middle of the night in Australia, Facebook announced that it would strip all news content from the feeds of Australian users and block Australian news media from sharing content on the platform.

Facebook had previously threatened to do this if the Australian government enacted legislation requiring internet giants like Facebook and Google who shared links to news content to split the revenue derived from that content with media companies. However, their decision to do this before the legislation had even passed the Australian parliament took many by surprise.

_______________________________________________________________________

In addition to news media pages, the sweeping ban took down a raft of pages from community groups, NGOs and not-for-profit organisations. This affected issues such as weather (including extreme weather warnings, such as cyclones or dangerous bushfires, which are critically important in many regions of Australia) as well as health pages.

Five days later, on Tuesday 23 February, the Australian government announced changes to the legislation. In response, Facebook said it would allow Australian users to access news content again. But at the time of writing (the morning of Thursday 25 February in Australia), news links remain blocked and the Facebook pages of news media and many other organisations also remain blank for Australian users.

Screenshot of the New York Times Facebook page viewed from Australia during the news ban.

Australians have now spent a week on Facebook without the ability to see or post articles from recognised news media on the platform. The timing of Facebook’s announcement of the ban is also particularly notable – as it comes just days before the beginning of Australia’s COVID-19 vaccination program, and the launch of a voluntary code from tech giants including Facebook aimed at fighting disinformation in Australia, both of which happened on Monday 22 February.

The combination of these factors has created a fascinating, albeit short-lived, experiment: what happens to disinformation and conspiracy theories in the absence of journalism on social media platforms?

About 39% of Australians used Facebook as a source of news before the COVID-19 crisis. This climbed to 49% during the pandemic as Australians significantly increased their news consumption overall, according to a 2020 study. However, just 6% of Australians rely on Facebook as their sole source of news. Television is still their main source of news.

Nielsen data showed a 16% drop in traffic to Australian news sites on the first day of the ban. The ABC reported that Chartbeat data showed a 13% drop in traffic to Australian news websites from within Australia, and a 30% drop in international traffic.

It’s hard to say how these drops in traffic might have developed if Facebook had not been satisfied with the government’s amendments to the legislation, and had instead chosen to maintain the ban over a longer period. But based on the observation of conspiracy communities’ activity on Facebook over the past week, there are several points we can consider about how they adapted to the absence of legitimate news media on the platform.

Conspiracy communities adapted fast

Users in both general Facebook groups and in conspiracy groups have consistently found ways to circumvent bans, for example through screenshots of articles published on media sites; through copying and pasting entire article texts into their posts; or through breaking up the link in a way which still allows it to be posted (e.g. “abc[.]net[.]au/…”). Users are also increasing their use of news shared via YouTube, which is not blocked.

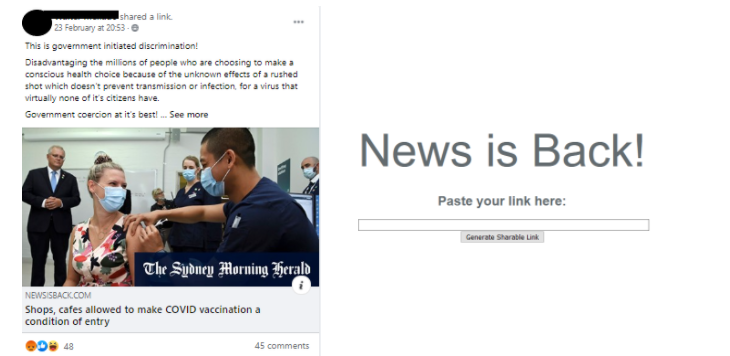

By the end of the week, a website had been created specifically for domain cloaking to share news on Facebook and was in use by both general users and conspiracy theorists.

Screenshot of the News is Back domain cloaking page (left) and the service used to share a news article to a conspiracy group (right).

Through Facebook’s earlier bans on COVID-19 misinformation, anti-vax and QAnon content, among others, conspiracy communities are already familiar with various methods for circumventing bans. They appear to be adapting easily to the blocking of mainstream news outlets by using these same tactics and the ban appears to have caused little – if any – disruption to these groups.

In what is also likely a bonus for conspiracy groups, Facebook’s ban on news has also been a de facto ban on most fact-checkers. While Australian users continue to see pop-ups from Facebook on certain content, directing them to information from the World Health Organisation, many fact-checks on specific pieces of disinformation are also blocked.

To give one example, a piece of misinformation about supposed ‘Covid kits’ in India that was earlier circulating in African Facebook groups is now circulating in Australian conspiracy groups. It has already been fact-checked by African media, but that fact-check cannot be shared by Australian users.

Screenshot of attempt to share ‘Covid kits only distributed in one Indian state, not cause of national decline in cases’ fact-check from Africa Check.

Predictably, some conspiracy theorists see the ban as – you guessed it – part of a conspiracy (for example, to avoid having to report on supposed deaths caused by vaccines). Others have responded with glee at seeing the ‘MSM’ (mainstream media) be subjected to a similar ban that many sources of misinformation and conspiracy theories have experienced in recent months. They see this as an opportunity to ‘fight back’ and drive the narrative.

Conspiracy Theorists: Bigger Fish in a Smaller Pond

The gap left by legitimate media organisations has left room for conspiracy theorists to play a proportionately larger role in activity on Facebook. One example is in the narrative around conspiracy theory protests.

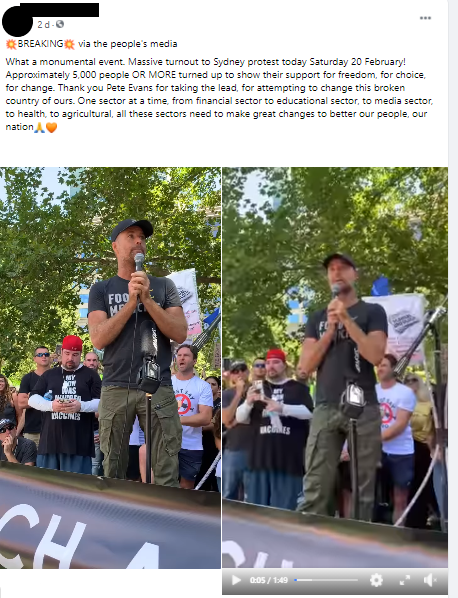

Over the weekend, coordinated anti-vaccine and Covid-sceptic protests took place in capital cities across Australia. The protests were organised largely on Facebook. Like many conspiracy communities around the world, Australian conspiracy theorists are prolific Facebook content creators, and on the day of the protests a multitude of livestreams, photographs and after-action reports were shared on the platform.

In previous conspiracy protests, this wave of content was met and to some degree countered through coverage from legacy media. This time around, however, conspiracy theorists had largely unchallenged control over how their protests were portrayed on Facebook, including inflating the size of the turnout and spreading rumours about police responses.

Screenshot of Facebook post showing video from the protest, claiming a turn-out of “5000 people OR MORE.” Media has reported the turn-out as being ‘hundreds’.

This dynamic is beginning to show up in data. On Monday, the official start of Australia’s vaccination program, four of the top 20 most engaged Facebook posts for ‘vaccine’ (from English-language Australian Facebook pages) came from pages that have previously promoted conspiracy, anti-vaccine or anti-lockdown content.

ISD has also compared the top 50 most engaged Facebook posts for ‘vaccine’ from English-language Australian Facebook pages for the week from 11-18 February, the week before the news ban, and 18-25 February, the week of the news ban (which began on the 18 February), using data collected from Crowdtangle on the 25 February. The roll-out of the vaccination program in the same period is also obviously a complicating factor here, but the comparison is nonetheless interesting.

In the week before the news ban, the top 50 posts came from pages which included:

➜ 29 news media pages

➜ 12 politicians and political party pages

➜ 1 government page

➜ 3 conspiracy pages

During the week of the news ban, the top 50 posts came from pages which included:

➜ 21 politicians and political party pages

➜ 14 government pages

➜ 6 conspiracy pages

The doubling of conspiracy pages making the top 50 for this topic is certainly interesting, but it should not be misinterpreted as a doubling of conspiracy-linked activity on the platform. It is not evident that there has been any major growth in conspiracy communities in the past week. Rather, because the news media is gone, the activity of conspiracy communities is making up a larger proportion of the overall activity. In other words, the pond shrunk and the minnows appeared larger.

Assuming Facebook does return access to news for Australian users in the coming days as promised, the immediate impact for users is likely to be short-lived. Many Australians may barely have noticed that the ban happened at all. As a form of natural experiment, however, it has been interesting to observe how swiftly and easily conspiracy communities adapted, and even began to benefit, from the absence of legitimate news media.

At a broader level, a precedent has been set through this episode which is likely to have substantial ramifications. Facebook was able to swiftly catalyse significant legislative concessions through these actions. The repercussions of this on the relationship between major tech platforms and governments across the globe is something we will likely see play out over the coming years.

Elise Thomas is an OSINT Analyst at ISD. She has previously worked for the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, and has written for Foreign Policy, The Daily Beast, Wired and others.