What can the Most Shared URLs on Social Media During the French Election Tell Us About Public Opinion of the Vote?

4th May 2022

By Roman Adamczyk and Zoé Fourel

This Dispatch is also available in French.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Measuring the prevalence and impact of extremist discourse and online disinformation on an election campaign is challenging. Positive electoral outcomes for candidates belonging to extreme political movements can indicate that their campaign’s online communication strategies were effective. However, this alone is insufficient to understand the full dynamics and the extent to which polarising or extremist narratives and misinformation may have impacted voters’ choices.

As several recent studies have shown, Twitter cannot be considered a space that represents the opinions or concerns of a whole population. However, during the French presidential campaign, it remained an ecosystem where the main actors (media, candidates, political activists) were extremely active. As such, the most shared election-related links on Twitter can provide an understanding of the actors, themes and content that dominated a section of online discussion during the presidential campaign.

This analysis examines the most widely shared election-related links (URLs) on Twitter during the French presidential campaign period (5 March 2022 to 10 April 2022). Specifically, it looks at the most widely shared links in posts that either referred to the presidential election, or mentioned the name of at least one of the presidential candidates.

As part of this analysis, ISD also examined the most shared election-related links in specific French-language conspiracy, extremist and anti-establishment communities on Facebook and Twitter. Drawing comparisons between the links that circulated in a generalised online ecosystem (Twitter), and the links that circulated in specific, radical communities, allowed us to understand the precise cross-platform dynamics at play during a presidential election.

This study covers a limited period of the presidential campaign and explores a limited part of the online ecosystems that may have played a role in the election results. Some of the discussions analysed include both legitimate concerns for democratic debate and concerns that may have been instrumentalised for political purposes, reflecting the complexity of online exchanges.

Key findings

➜ On Twitter, the main themes of discussion were relatively similar to those in extremist, conspiracy and anti-establishment communities. The exceptions to this were topics such as COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine, which were discussed in fringe communities but less so in mainstream spaces.

➜ Sources differed between communities. ISD identified a higher proportion of content originating from unreliable or politicised sources within extremist, conspiracy and anti-establishment communities, with messages more likely to include misinformation and polarising rhetoric.

➜ The 100 most shared links on Twitter mostly redirected to content produced by traditional (57%) or opinion media (19%), highlighting how media coverage of the presidential campaign remained the most important source of content and commentary on Twitter.

➜ In the weeks leading up to the elections, ISD observed distrust in the democratic process and the fairness of the campaign. This was most noticeable in extremist and political ecosystems on Twitter and Facebook, but was present in the most widely shared links on Twitter as whole.

➜ In terms of political content, links to pro-Zemmour content were particularly prevalent in the fringe communities analysed. Some of these links were also shared widely on Twitter. This highlights Zemmour’s polarisation of wider audiences, as well as the efforts of his campaign to occupy online discussion – sometimes employing information manipulation strategies.

Methodology

This analysis covers the period from 5 March 2022, the day the official list of candidates for the election by the Constitutional Council were released, to 10 April 2022, the day of the first round of the presidential election.

During this period, ISD collected the 100 most shared links in French tweets that included either the name of at least one presidential candidate or one of the following words: “election”, “presidential”, “elections”, “presidential”, “campaign” and “polling”.

Using the same criteria and keywords, ISD also collected and analysed the 100 most shared links about the presidential election in extremist, conspiracy and disinformation-sharing communities on Twitter and Facebook. These communities had been identified in a previous (unpublished) study by ISD.

Analysis of the most shared links on Twitter

Mainstream and opinion media sources

Among the 100 most shared links on Twitter, 57% redirected to content produced by mainstream media sources (such as Le Monde, BFMTV and the Huffington Post), illustrating that traditional media sources continued to occupy a prominent role in online discussion around the presidential campaign.

Drawing on research by the Sciences-Po MediaLab, which employs categories to map the French media ecosystem, 19 of the 100 most shared links were categorised as opinion or independent media. The category comprised media sources which have a strong political stance. On the left, this included e.g. Mediapart, l’Humanité, Alternatives Economiques and Blast, and on the right this included e.g. CNews and Valeurs Actuelles. These outlets are relatively well integrated with more traditional media information ecosystems. Some of these outlets, particularly on the extreme right, are considered to have an important role in amplifying disinformation and polarising discourses.

Partisan and disinformation sources

11 of the 100 most shared links were produced by the political campaigns of the main presidential candidates (i.e. campaign sites, YouTube channels). Although there were many more links to media articles (57) than to political campaigns in the 100 most shared links on Twitter, two links to political campaigns were amongst the top 10 most shared links overall, with 10.7k and 17.9k shares respectively. This observation shows that content from partisan sources can, in some cases, obtain high levels of engagement on Twitter.

In total, 7 of the 11 links were produced by the Éric Zemmour campaign, reflecting the campaign’s online mobilisation efforts to ensure high visibility on Twitter. According to several investigations, these efforts involved online manipulation strategies. Among these 7links were two petitions from members of the Reconquête party. One petition sought to denounce the relationship between Emmanuel Macron and the firm McKinsey the other was in support of a farmer under investigation for killing a burglar.

A further 6 of the 100 most shared links were identified as coming from media outlets known to spread disinformation or conspiracy theories (Le Courrier du Soir, Anguille Sous Roche, Apar.tv, Planètes 360, Le Courrier des Stratèges and Quoi2News), and one link came from an extreme right-wing website (FdeSouche). These links were shared between 3,600 and 8,500 times, illustrating the wide circulation of some content from unreliable or polarising sources.

Anti-establishment rhetoric & controversies surrounding Macron

From a thematic perspective, ISD found that 43% of the most shared election-related links on Twitter directed to content covering controversies targeted at President Macron. These attacks against Macron were part of larger narratives around politicians being considered as corrupt, defending only big companies and the rich. This content came from mainstream and opinion press, and included debate over the ‘McKinsey affair’, as well as unproven accusations that Macron avoided paying tax when he worked for the Rothschild bank. Links to this content were often shared alongside messages containing legitimate concerns about political ethics or public spending.

As the title of an article by the fact-checker Les Décodeurs (“McKinsey and Macron: the truth and falsehood of the controversy’) would suggest, online discussion of the controversies surrounding Macron consisted of truth, speculation and lies. For example, prior to the first round of the presidential election, there was significant focus on distrust of the political elite and Emmanuel Macron’s personality in online discussion. This echoes another study conducted by ISD which highlighted how the amplification of anti-establishment rhetoric on social networks favoured extreme positions and weakened the Republican front.

Figures 1 and 2: Screenshots of tweets criticising Emmanuel Macron and the state over the ‘McKinsey affair’.

Content related to Reconquête candidate Éric Zemmour

On Twitter, 19 of the 100 most shared links either came directly from Éric Zemmour’s campaign (7), or related to Zemmour or his party (12 links). One example was an article by Éric Zemmour in the far-right outlet ‘Valeurs Actuelles’, in which he decried the death of Jeremie Cohen (a young man who died as he was trying to flee his aggressors, a case that inspired much discussion in France). Another was an interview of the far-right candidate for the media Le Figaro, where he presented himself as the solution to “save France”.

In the top 10 most shared links on Twitter, there was also a public call to action in the Trocadero rally of the Reconquête movement, and a petition from Zemmour’s campaign which attacked Macron over the “McKinsey affair”. The high share count of Zemmour-related content did not always correspond with positive sentiment. Media coverage of Zemmour’s expulsion from a football field by the brother of former footballer Zinedine Zidane, for example, was shared by many on Twitter to criticise Zemmour’s extremist political positions.

Figure 3: Screenshot of a tweet welcoming the exclusion of Éric Zemmour from an indoor football club run by the brother of former footballer Zinédine Zidane.

Online discussion about the vote

Although more limited in number, ISD identified 12 links shared in tweets questioning the fairness of the presidential campaign and the integrity of the vote. In this category, some posts presented legitimate opinions regarding democratic processes in France, whilst some included conspiratorial messages about the conduct of the campaign and democracy in France.

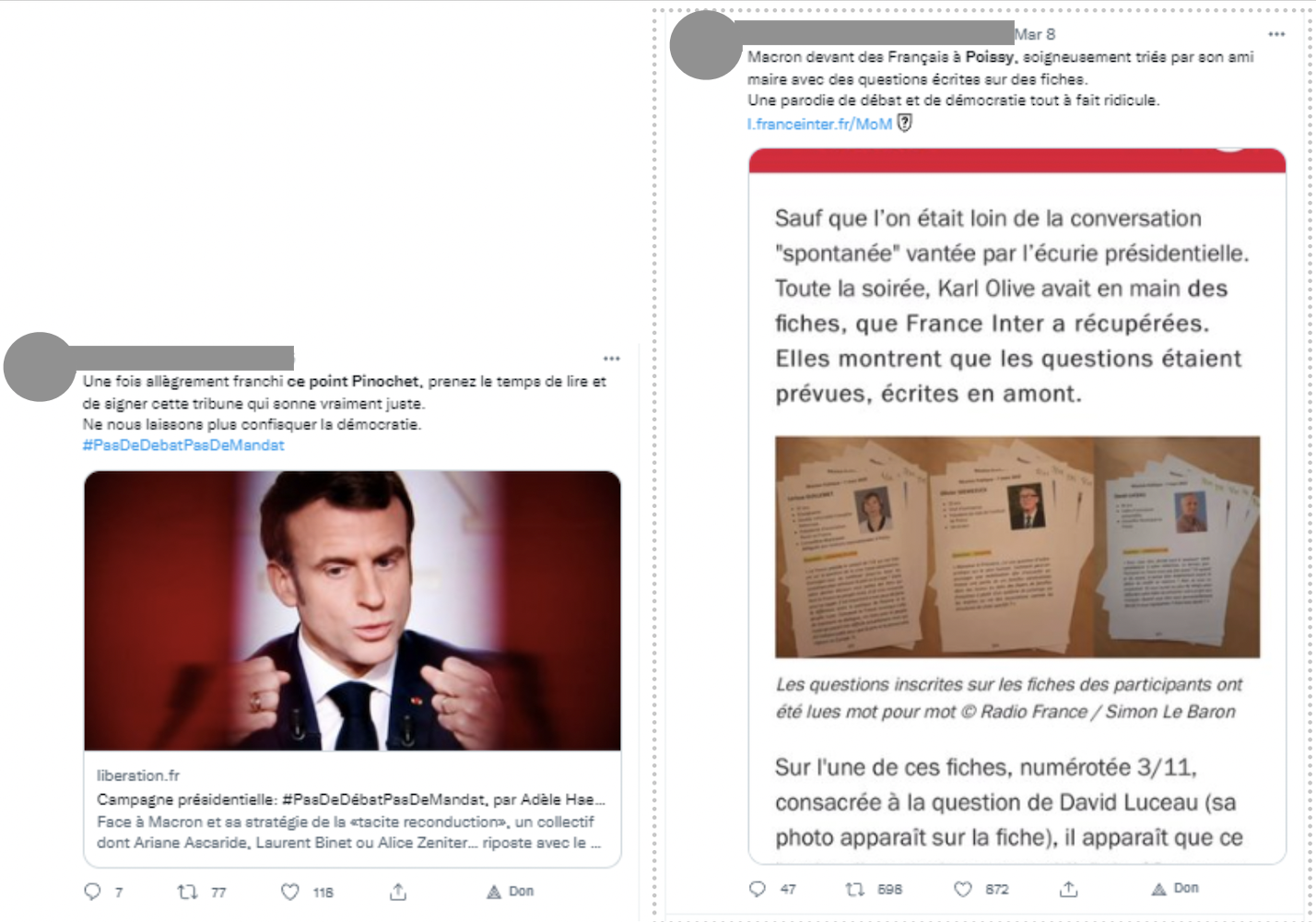

For example, a France Inter article showing how the questions in Emmanuel Macron’s first debate with citizens in Poissy were prepared in advance was the link that had the highest number of shares on Twitter during our period of analysis, with tweets accusing it of a “parody of democracy”. Similarly, the “No Debate, No Mandate” op-ed, which was published by a group of writers and activists and claimed that Macron’s decision to not participate in debates ahead of the first round was anti-democratic, was widely shared on Twitter to question the democratic nature of the first phase of the campaign.

Amongst the 100 most shared links, there was also an article from the conspiracy website Anguille Sous Roche, which accused Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg of rigging the Michigan election in Biden’s favour (Figure 6). Some tweets drew a parallel between this article and a possible future manipulation of the French elections.

Figures 4 and 5: Screenshots of two tweets presenting Emmanuel Macron’s campaign choices and practices as anti-democratic.

Figure 6: Screenshot of a tweet linking to a conspiracy website’s article accusing Facebook of participating in alleged voter fraud to get Joe Biden elected”. Is it possible to do this small modification?

The Russia-Ukraine war

Only 5 of the 100 most shared links around the presidential election made reference to Ukraine, suggesting that the topic was not central to general discussion on French-speaking Twitter in the final weeks of the campaign. However, 2 of the 5 links redirected to content from TF1’s 14 March TV programme “La France face à la guerre”, where several presidential candidates were interviewed about their position on the Ukrainian conflict. This would suggest that French Twitter was interested in the subject and its impact on the presidential campaign.

Two additional, widely shared links related to Ukraine were to the same episode of RMC’s “Les Grandes Gueules” programme, a radio talk show where journalists, political activists and other civil society actors talk about the French news cycle. In this episode, a participant claimed that the meeting of EU leaders in Versailles to discuss the war in Ukraine was a strategic political move by Emmanuel Macron.

Finally, a widely shared tweet included a link to the Telegram channel “Quoi2news”, which was identified in a note on sectarian aberrations by the French Ministry of the Interior as a source of conspiracy theories. The link is to a video of an interview in which Macron’s slip of the tongue over France’s past negotiations with Russia over the Ukrainian conflict (“I fully assume to have constantly, in the name of France, spoken to the president of Russia… to avoid peace!”), was used by conspiracists to attack Macron. In the interview, Macron had corrected himself directly after this slip up, saying that he had obviously meant to say “avoid war”.

Analysis of the most shared links in conspiracy, extremist and anti-establishment ecosystems

In the conspiracy, extremist and anti-establishment communities analysed, the most shared links around the presidential campaign predominantly came from political sources (33% vs. 11% of the most shared links on Twitter) and from sites known to spread disinformation or extremist rhetoric (16% vs. 7% for the most shared links on Twitter). Even within these communities, however, content from mainstream media (29%) and the opinion press (13%) was shared widely, highlighting the importance of media coverage in the overall discussion about the campaign.

Prevalence of content related Éric Zemmour

While content related to Éric Zemmour’s campaign already had a significant presence in the links that circulated most around the presidential election on Twitter (19%), links to this content represented 48% of the most shared links in the extremist, conspiracy and anti-establishment communities that ISD explored. 60% of Zemmour-related content was produced directly by official channels of the far-right politician’s campaign (Youtube channel, campaign sites). The remaining 40% was coverage of his campaign by mainstream or opinion media, the latter often having a strong right-wing political orientation. The most shared links on Zemmour from media outlets often came from media classified as far-right or conservative, and presented the information with a pro-Zemmour bias. One example of this was an article from Valeurs Actuelles, which described Zemmour’s social media strategy as an undeniable success.

Figure 7: Screenshot of a tweet from an article in Valeurs Actuelles presenting the digital strategy of Eric Zemmour’s campaign as an “overwhelming success”.

ISD researchers also observed articles from mainstream media which reported on events that took place during Éric Zemmour’s campaign, and presented Zemmour to his advantage. This includes, for example, several articles in Le Figaro and the local media Sud-Ouest announcing that various public figures left the conservative political party Les Republicains to join the Eric Zemmour campaign. Some of these articles on political figures joining the Zemmour campaign also appeared in the most shared links on Twitter identified overall.

Macron-related content

Of the 100 most shared links in the conspiracy, extremist and anti-establishment communities analysed, 40 were about Emmanuel Macron and often included harsh criticisms of and attacks against the incumbent president. The majority of content focused on the ‘McKinsey affair’, unproven accusations of Macron committing tax fraud, and broader anti-establishment narratives against the French government (51%). The Zemmour campaign’s petition attacking Macron over the McKinsey affair, as well as Off Investigation’s investigation which claimed that Macron had funds hidden in a tax haven, were among the most shared links in these alternative online ecosystems, and were also in the 100 most shared links on Twitter.

By contrast to the most shared links on Twitter, which included mainly anti-Macron positions that focused on the controversies at the centre of the news cycle, the most shared links about the French president in the conspiracy and extremist communities of analysis touched on a broader spectrum of topics, such as the Russia-Ukraine war and COVID-19. This is partly due to the fact that these communities regularly shared content from prominent French conspiracy sources such as the France-Soir or Courrier des Stratèges websites (35%). Links to articles from these websites were often used to reshare conspiracy theories adapted to the current campaign and in opposition to Macron’s reelection, by for example accusing him of being part of a conspiracy to establish a New World Order or attacking him for his management of COVID-19.

Figure 8: Screenshot of a tweet from the conspiracy website “Le Courrier des Stratèges” encouraging people to vote against Emmanuel Macron because he allegedly secretly organised the euthanasia of elderly people during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Four of the 100 most shared links attacked Macron’s strategy on the war in Ukraine. This included an article from the conspiracy blog Le Courrier des Stratèges and an article from the conspiracy website SOTT, which contained a number of videos from the controversial French journalist Anne-Laure Bonnel claiming that Macron was lying to the French about the war in Ukraine and the situation in Donbass. The journalist caused controversy during an appearance on the TV channel CNEWS by spreading misinformation about the conflict in Donbass and is presented by several media as a source of amplification of pro-Kremlin narratives.

Figure 9: Screenshot of a tweet including a link to an article from the conspiracy website SOTT, which includes videos by independent journalist Anne Laure Bonnel accusing Emmanuel Macron of lying about Ukraine.

Public initiatives seeking to monitor the vote count to avoid the perceived threat of voter fraud

Finally, two of the 100 most shared links in fringe communities were to initiatives that sought to gain citizen control of the vote count in the presidential election. These initiatives, which present themselves as the result of citizen mobilisation, have in fact emerged from conspiracy communities and communities promoting anti-establishment rhetoric. They started to mobilise in mid-March on the assumption that the results of the presidential election would be manipulated to favour the presidential majority camp.

One of these citizens’ initiatives is linked to the Bon Sens association. This association was founded by several figures of the movements opposed to health restrictions and COVID-19 vaccination in France, such as Xavier Azalbert who is the owner of France Soir, a major website amongst French conspiracy communities.

Figure 10: Capture d’écran d’un tweet de l’association Bon Sens qui promeut une des initiatives de contrôle citoyen du vote lors de l’élection présidentielle.

Conclusion

During the French presidential campaign, the most popular topics of online discussion were relatively similar in both the broad information space of Twitter, and the smaller extremist, conspiracy and anti-establishment communities. The exception to this was content about COVID-19 and the ongoing war in Ukraine, which circulated widely in fringe communities, but not in broader conversation.

Our study shows a convergence of engagement across communities with content centred around a mistrust of the political and institutional systems, which often mixed legitimate concerns with more direct, political attacks.

Éric Zemmour was the most mentioned presidential candidate both on Twitter and in more specific communities, which indicates the online mobilisation efforts of the Reconquest campaign, but also brings into question the campaign’s online manipulation strategies.

However, despite some similarities, it is important to note that content from political actors and unreliable sources (which were more likely to include misinformation or extremist rhetoric) had more difficulty achieving high virality on Twitter than in the extremist, conspiracy and anti-establishment communities of analysis.

Finally, ISD noted that concerns about the fairness of the election campaign and the integrity of the vote were present in the different environments covered by our analysis. According to an IFOP poll, 14% of French people believed that the presidential election could be rigged before the second round. The relative success of electoral fraud narratives beyond online fringe communities serves to illustrate the significance of institutional distrust in France, and the need to rebuild trust in democratic processes.