RT Articles are Finding their Way to European Audiences – but how?

20 July 2022

By Kata Balint, Francesca Arcostanzo, Jordan Wildon & Kevin Reyes

From 2 March 2022, the broadcast of and access to RT (Russia Today) and its various language versions were suspended within EU Member States. The EU’s sanctions cover all means for the transmission and distribution of RT content, including on social media and search engines. Despite this, ISD analysts have observed that content from RT is still accessible via websites that feature their articles, often word for word.

ISD designed a case study approach that looked at RT articles about Ukrainians seeking refuge in Europe. This Dispatch outlines how such articles have found their way to European audiences despite the EU-wide ban on the outlet’s content.

_________________________________________________________________________________

To summarize: How has Russian state media content reached EU audiences?

ISD identified four different types of websites that are providing loopholes for RT content to reach the EU information space. These are:

- Variations of RT domain names that direct to RT servers and were created after the start of the invasion;

- Mirror websites that are identical to RT’s ‘official’ sites, but could not be directly attributed to the outlet;

- Websites that copy-paste articles from RT in their entirety;

- Websites that direct traffic to RT.

For some of these websites, analysts found indications of monetization. The first two categories, the alternative RT domains and mirror websites, have amassed millions of views over the past months. This is thanks, at least in part, to their content being shared across social media by official RT accounts.

Posts that link to these domains have been shared over 456,000 times on Twitter and Facebook, with a significant peak identified at the beginning of April. While RT Facebook accounts are not accessible from a European location, on Twitter the ban can be circumvented by manually changing the location settings of one’s account. Furthermore, the websites these posts promote continue to be listed in Google search results, potentially driving traffic from the search engine to RT content.

Methodology

This investigation, carried out between the end of June and the beginning of July 2022, focused on the language versions of RT that are banned within the EU. These are RT English, RT Germany, RT France, and RT Spanish. To identify the relevant set of RT articles, analysts developed a search query in each of these four languages that included the various versions of the terms “refugee”, “asylum-seeker” or “migrant”, in combination with the terms “Ukraine” or “Ukrainian”.

Analysts used a VPN to mask the geographic location of the analysts and to avoid restrictions accessing RT websites. 236 English, 269 German, 38 French and 41 Spanish official RT articles were identified as containing the search terms, as indexed by Google. These articles were manually vetted and filtered so that only articles that could be construed as implying and focusing on the negative consequences of the arrival of Ukrainian refugees remained in the sample set. This resulted in 15 English, 30 German, 10 French and 11 Spanish articles.

The most common narratives present in this set of RT articles were:

- Preferential treatment of Ukrainian refugees compared to other refugees in host countries;

- Stretched resources and the cost of admitting Ukrainian refugees to the host country;

- Security risks to the host country, such as integration issues and the perceived aggression of refugees;

- Mistreatment of Ukrainian refugees;

- Disadvantages for Russian-speaking Ukrainian refugees;

- Ukrainian women being portrayed in a sexualized manner;

- Lack of help from the US and UK for European countries hosting Ukrainian refugees;

- Migrants from other countries taking advantage of the Ukraine crisis.

Examples of RT articles.

In order to surface the websites that host and publish RT content but are currently not subject to sanctions, analysts searched the titles of these original articles using Google and collated the results for further analysis. This resulted in 425 English, 292 German, 38 French and 105 Spanish websites that were indexed by Google as featuring the exact titles of the related RT article. After manually assessing these websites, analysts categorized and investigated the nature of these domains using OSINT techniques.

What did we find?

- Alternative domains and subdomains for RT

Analysts identified 12 domains that are identical to RT. These websites had different URLs that resolve to official RT IP addresses, as well as an additional two subdomains with similar qualities. The latter seems to be used to test the evasion of restrictions, with domain names containing terms such as “against censorship” and simply “test”.

12 of these domains were registered in Moscow and hosted by an entity called RU-CENTER. 11 were created in the six-week period following Russia’s invasion: 1 English domain on 5 March, 7 German domains on 6 April, and 3 Spanish domains on 8 April. The English-language created in 2017 were registered to ANO TV-Novosti, the parent company of RT.

- Mirror websites of RT

Five additional domains were identified as mirror websites of RT. A mirror website is an identical copy of a website that is placed under a different URL. Hence, the mirror websites identified here are identical to RT but are hosted on servers that cannot be attributed to RT. However, there is no clear indication that these websites are affiliated to RT or are in any way connected to each other.

- Copy-paste websites

The most prevalent type of website was copy-paste websites, with a total of 112 domains identified. These featured RT’s articles in their entirety. The architecture and registration details of many of these does not imply affiliation to RT. However, there are certain websites that seem to be connected as a result of being registered by the same entity. An example of this is an organization that registered seven of these copy-paste websites, signifying a network between them.

Internationally renowned web hosting companies are also providing services to the actors behind these domains. For example, GoDaddy, a domain registrar and web hosting company based in the US, hosts 32 of these websites.

- Aggregator websites

46 additional websites were discovered that only feature part of an RT article, such as the title, the lede, or the first few paragraphs. These direct traffic to official RT websites by linking to the original article.

Figure 1: The categories and quantity of discovered websites.

One of RT’s official domains, ‘deutsch.rt.com’, also showed up in our search. Analysts observed that from certain locations within the EU, these articles could be opened, meaning that despite the ban even an official RT domain can be accessed by European audiences via a simple Google search.

For a number of the URLs that were indexed by Google as featuring the exact title of the articles, analysts were unable to identify the titles or any other part of the article on the site. Subsequently, these websites were not categorized and were excluded from further analysis.

43 of the copy-paste websites, 3 alternative RT domains and 1 mirror website were found to have a Google Analytics ID. Google Analytics is a web analytics service that tracks web traffic and visitors’ behavior on one’s website.

Web traffic

Web traffic data could be collected for eleven alternative RT domains and two mirror websites. During May, there was an aggregate of more than 2,593,000 visits to these sites, and more than 2,490,000 within the month of June. To put this in broader perspective, the website of the European outlet of Politico ‘politico.eu’ amassed 4.5 million visits in June.

1.2 million of the visits to these domains in May (48%) were to one of the Spanish alternative domains – ‘actualidad-rt.com’. In June, the Spanish ‘esrt.press’ amassed 1.1 million visits out of the aggregate 2.5 million (44%). In June, the primary audience for these sites was based in Spain, with 88% of traffic to ‘actualidad-rt.com’ and 43% to ‘esrt.press’ coming from Spain.

Spread on Twitter and Facebook

To quantify the spread of the alternative RT and mirror domains on social media, ISD analysts examined the spread of links referring to the identified domains (12 alternative domains, 2 alternative subdomains and 5 mirror websites). Using the social listening tools Brandwatch and CrowdTangle,

As shown in Figure 2, Twitter and Facebook posts linking to these websites were almost entirely absent prior to the implementation of the EU ban. As of 1 April 2022, however, they saw significant traction on the two platforms.

Figure 2: The graph above shows the spread of alternative RT domains on Facebook (red) and Twitter (blue) from 1 February to 30 June 2022.

On both platforms, the main accounts responsible for the spread of these links were accounts tied to RT itself. On Facebook, most of the posts sharing links to alternative RT and mirror domains came from official RT pages. In particular, RT DE shared links to these websites 1,610 times in the period analyzed, RT Latinoamérica 680 times, RT Futuro 438 times, and RT Viral 129 times.

On Twitter, the most prolific author was found to be the Spanish-language RT account, ActualidadRT, which shared the links over 9,000 times. Fifteen other accounts were found to have shared the links more than 1,000 times in the period analyzed. Aside from RT DE, all the other accounts are tied to Spanish-speaking individuals seemingly based in Latin America.

The increase in the spread of messages including these links starting from 1 April 2022 was primarily due to retweets of Spanish RT accounts, namely RTultimahora and ActualidadRT. On 1 April alone, 36 tweets from these two accounts linking to alternative RT and mirror URLs received a total of 2,637 retweets.

Pushing alternating domains on Twitter: the case of RT Spanish

To shed light on the tactics used by RT to promote these domains, ISD looked at all content posted by ActualidadRT on Twitter since 1 February and analyzed which websites the account had been directing traffic to.

As shown in Figure 3, the RT account appears to switch the use of different websites during particular periods. Between 1 February and 1 April, the account exclusively shared links to the pages ‘es.rt.com’ and ‘actualidad.rt.com’, both subdomains of the official ‘rt.com’ website. From 1 April to 18 May, the account appeared to switch to sharing the website ‘actualidad-rt.com’, which was then gradually replaced by the website ‘esrt.press’, seemingly to evade restrictions.

From the end of June, a fifth alternative domain, estr.online, began to be shared on Twitter. It is worth noting that the account did not stop sharing the other domains; it was sharing multiple domains at the same time.

Figure 3: The graph above shows the volume of shares of different websites linked to RT by the account ActualidadRT from 1 February to 30 June 2022.

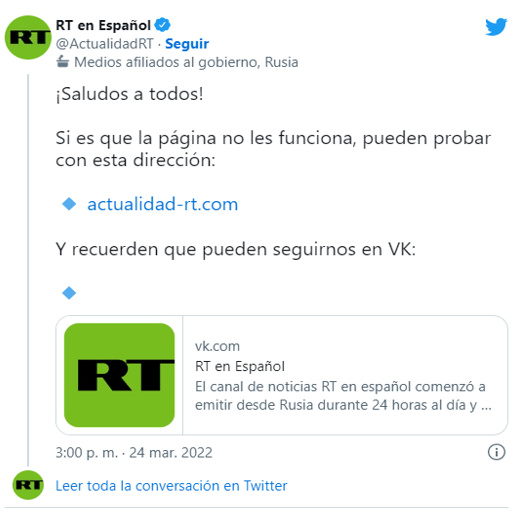

Figure 4 shows a tweet from ActualidadRT posted on 24 March 2022, promoting ‘actualidad-rt.com’ (one of the alternative URLs) stating “if the page does not work, you can try this address”.

Figure 4: A tweet posted by RT in Spanish announces “Hello everyone! If the page does not work, you can try this address: actualidad-rt.com. And remember that you can follow us on VK.”

None of the Twitter and Facebook accounts affiliated with RT are available to European audiences and no other official RT account could be accessed from a European location. However, on Twitter, if a user changes their location manually to a country outside of the geo-ban, these entities become accessible, despite the user’s IP address indicating that they are located inside the EU. This means that self-declared location is the primary signal used in deciding whether they are able to access RT content, rather than where the individual is actually based. In turn, this highlights that the ban on RT accounts on Twitter can easily be circumvented from within the EU.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this analysis, the following recommendations are proposed to enhance the policy response to the threat of information manipulation by Russia:

- European regulatory bodies should monitor websites that either feature content from RT, such as the alternative RT domains, mirror websites and copy-paste websites, or that redirect traffic to RT, in order to adapt and ensure the effectiveness of policy responses to state-controlled information manipulation. Once attributed to the Kremlin, these entities should be sanctioned in a similar fashion to the official RT domains, especially in the case of those with alternative domain names but identical content.

- European regulators should also complement policy responses by restricting monetization via advertising for websites that feature RT content or direct traffic to its domains. Ad tech companies could play a key role in restricting advertising for these actors.

- National regulators should consistently enforce the ban on RT’s official websites across platforms and geographies within the EU, as some of these domains of the outlet are still accessible from various locations in Europe. Furthermore, in light of the circumnavigation tactics observed, it is clear that these bans should be strengthened and include the circumvention infrastructure of RT.

- Tech companies, such as Google, should renew efforts to remove official RT domains and alternative domains connected to the outlet from their search results. Similarly, social media companies should ensure the comprehensive enforcement of the ban. This is particularly pertinent to Twitter, whose platform appears to be restricting access to RT official domains on the basis of user-reported location rather than IP address or other geolocation signals.