Jan 6 series: How OSINT powered the largest criminal investigation in US history

By: Kevin D. Reyes

14 February 2023

This Dispatch is part of ISD’s series marking the anniversary of the January 6th insurrection, exploring themes including accountability for big tech, extremists’ digital footprints, and the landscape of election denialism going forward. _________________________________________________________________________________

Photos and videos of the US Capitol attack of January 6, 2021, have been seen all over the world. Along with the social media posts associated with the attack, these images and videos make up the large digital footprint of January 6. Two years later, more than 940 people so far have been identified and charged with various crimes related to the attack in what has been referred to as “the largest criminal investigation in US history.”

This piece presents an overview of the multiple sources of publicly available evidence that make up the digital footprint of January 6 and how open-source intelligence (OSINT)* was used by law enforcement, Congress, journalists, and other researchers to understand what led to the attack and identify the rioters.

In order to examine the role of the attack’s digital footprint and the impact of OSINT, ISD reviewed charging documents for 940 Capitol riot defendants. We found that OSINT was the primary investigative method used to identify rioters. Our review also suggests that the large body of online evidence associated with January 6 and the use of OSINT by law enforcement led to more reliable and safer investigations. However, as a result of this mass of OSINT-powered cases, domestic extremists are becoming increasingly aware of their digital footprints and taking steps to reduce their vulnerabilities.

* For the purposes of brevity, this piece uses “OSINT” as a general term for digital open-source information, intelligence, investigations and research. For more on definitions, see the Berkeley Protocol on Digital Open Source Investigations.

Cameras everywhere

Donald Trump’s infamous tweet from December 19, 2020, urging his followers to attend the “big protest” on January 6, 2021, mobilized a variety of overlapping groups, from pro-Trump activists to followers of QAnon and anti-government militias. For the next several weeks, these groups openly planned demonstrations at the Capitol building via social media platforms and fringe websites such as TheDonald.win.

Once in Washington, the soon-to-be insurrectionists documented their visits and uploaded photos and videos to platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Parler. On the morning of January 6, they captured Trump’s rally speech and posed for photos with the city’s monument-filled background. The “several thousand” rioters who later stormed the Capitol documented the attack with their phones and GoPro cameras — some even livestreamed the event.

Aside from the rioters themselves, additional witnesses, including journalists, documented what was happening in the crowd and the experiences of those trapped inside the Capitol — lawmakers, staff and law enforcement — as people began to force their way into the building. Capitol surveillance cameras and body cameras worn by police officers were rolling. “Thousands of smartphones,” according to a New York Times analysis, set off “about 100,000 location pings” in or around the Capitol that day.

The January 6 insurrection was openly planned and livestreamed online. This content, and the online posts that praised the attack, make up the digital footprint of January 6 — a mountain of publicly available digital evidence that was ripe for open-source intelligence (OSINT), the driving force of “the people’s panopticon.”

How OSINT was used to investigate January 6

An army of journalists, civil society organizations, and online sleuths, as well as Congress and law enforcement, tapped into the overwhelming volume of digital evidence associated with January 6 to understand what led to the events of that day and identify who the perpetrators were. What follows is a general, but not exhaustive, overview of how these actors used OSINT to investigate January 6.

Law enforcement

The Department of Justice (DOJ) promptly reacted to January 6 and began its work to identify and prosecute rioters — an effort that has since been dubbed the “largest criminal investigation in the department’s history.” As of writing, more than 940 defendants have been charged with a variety of crimes including, among others, illegal parading; congressional obstruction; assaulting and resisting law enforcement; and seditious conspiracy.

To understand the role of the digital footprint of January 6 and the resulting impact of OSINT in greater depth, ISD conducted a comprehensive review of charging documents (criminal complaints, statements of fact, and indictments) filed against 940 Capitol riot defendants. Charging documents for 893 (95%) defendants contained details of how they were identified by law enforcement. Our analysis revealed that the vast majority (92.5%) of these 893 defendants were charged at least partly based on digital open-source research (i.e., OSINT). The documents were made available by the DOJ and George Washington University’s Program on Extremism.

While reviewing thousands of pages of charging documents for these defendants, ISD also found that the online platforms which served as OSINT sources included some of the most popular social media platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, Telegram, Twitter, LinkedIn, Parler and MeWe.

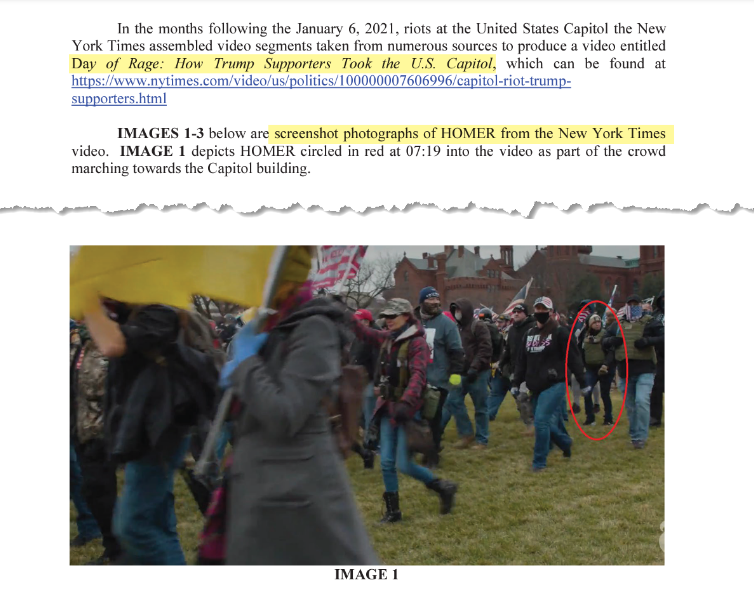

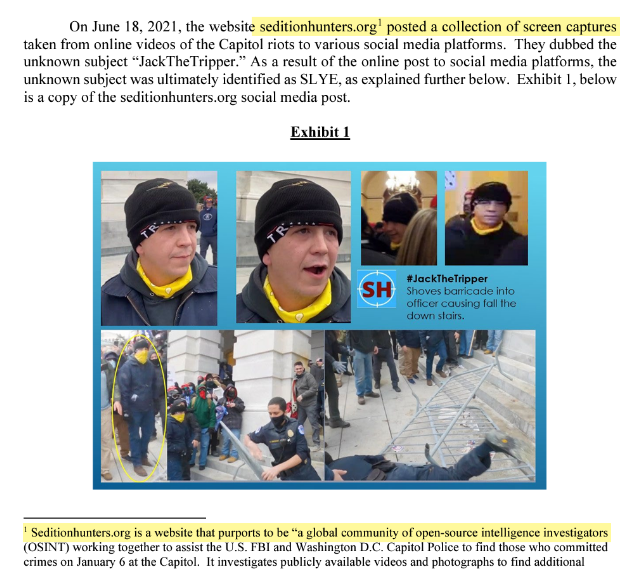

Many of these court filings specifically relied on OSINT-based reporting from journalists, tips from concerned citizens, and sleuth-led initiatives such as the Sedition Hunters. Figures 1 and 2 below, for example, present filings where law enforcement cited the New York Times visual investigation “Day of Rage” and work by Sedition Hunters in identifying the defendants.

Figure 1. Statement of facts in US v. Lisa Anne Homer citing the New York Times visual investigation “Day of Rage.” Source: US Department of Justice.

Figure 2. Statement of facts in US v. Mikhail Edward Slye citing open-source research by Sedition Hunters. Source: US Department of Justice.

ISD’s findings are consistent with similar research by journalist Mark Harris, whose analysis uses a broader definition of digital evidence that includes geofence warrants, surveillance video, facial recognition technology, and automatic license plate readers. Despite law enforcement’s use of these non-public sources, our analysis found that court filings for only 17 defendants (less than 2% of the total 940) did not mention OSINT but instead mentioned findings from body-worn cameras, CCTV footage, and/or social media and geofence warrants. This indicates that OSINT — the use of the publicly available digital footprint of January 6 — was the most critical investigative method in identifying and prosecuting Capitol rioters.

OSINT was also important for law enforcement in the lead-up to and during the attack. “We got derogatory [sic] information from OSINT suggesting that some very, very violent individuals were organizing to come to DC,” the January 6 Committee was told by Donnell Harvin, Washington’s former chief of homeland security and intelligence. Then, during the attack, Harvin “wasn’t watching on television like everybody else was. We have other means to look at some of these things, most of them as social media. People are live streaming them. … It’s OSINT.”

Congress

Rep. Jamie Raskin began the second impeachment trial against Trump on February 9, 2021 — this time as a response to January 6 — stating that “our case is based on cold, hard facts.” As part of the trial opening, the impeachment team played a 13-minute video compilation of the riot, which was entirely composed of open-source video footage from the crowd, the House Chamber, and tweets from President Trump.

Congress also responded to January 6 with the establishment of the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol. The committee’s final report, published in December 2022, details its findings in hundreds of pages and makes many references to OSINT-based analysis by journalists and other researchers.

The committee hired seasoned digital investigators to focus on the role of social media platforms in proliferating, amplifying and monetizing the election-related disinformation behind January 6. Relying on interviews and documents provided by social media companies and OSINT-based research, the team found that social media companies failed to both prevent the spread of election-related disinformation and act on extremists using their platforms to mobilize an insurrection. One key finding was that fears of accusations of censorship from conservatives “paralyzed” content moderation. It was only after the Capitol attack that moderation started to function properly. And although Harvin testified that law enforcement made use of OSINT to figure out that “very violent individuals were organizing” for January 6, the committee’s social media investigators also found that “social media companies largely did not receive clear warnings of violence from law enforcement before January 6.”

Both the impeachment team and January 6 Committee recognized the significance of January 6’s massive and poorly moderated digital footprint, and they strongly relied on the heavy lifting already done by journalists and other researchers who used OSINT to analyze and make sense of the attack.

Journalists & civil society

Journalists and researchers from civil society organizations swiftly responded to January 6 with high-quality, innovative documentation and analysis. These efforts in reconstructing the day’s events later allowed congressional investigators and law enforcement to quickly make sense of the attack and identify rioters.

In the days after January 6, the New York Times’s Visual Investigations team and the Washington Post’s Visual Forensics team both produced multiple timelines (here, here and here), using OSINT techniques such as geolocation to piece together photos and videos captured and posted on social media by rioters and witnesses. The combination of these timelines provided a remarkably detailed understanding of how the mob formed, then made its way to and breached the Capitol. Then, in late June 2021, the New York Times released a major 40-minute-long visual investigation, “Day of Rage,” which “synchronized and mapped out thousands of videos and police radio communications from the Jan. 6 Capitol riot, providing the most complete picture.”

Further analysis and rigorous online monitoring from civil society organizations such as the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), Bellingcat, and the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) reviewed the long, digital trail that precipitated the attack on the Capitol. They found that the Capitol insurrection was “not spontaneous,” but fueled by disinformation and conspiracy theories, and instigated by Trump and years of right-wing political violence in the US.

These journalists and analysts “had to act fast” to preserve as much content as possible, knowing that much of it would likely be deleted by the rioters themselves or taken down by social media platforms for violating their policies and community guidelines. ProPublica, for instance, archived more than 500 videos of the attack which were posted on Parler. These archival efforts were also critical in ensuring that the historical record of January 6 was as thoroughly verified and comprehensive as possible.

Other insights from January 6’s digital footprint

In the short and recent history of OSINT’s coming of age, scholars and practitioners have identified, examined and discussed several challenges presented by the use of this type of evidence in legal cases. This section argues that ISD’s review of Capitol riot charging documents indicates that the size of January 6’s digital footprint and the use of OSINT in criminal filings against Capitol rioters led to more reliable investigative findings and safer investigations, but that domestic extremists moved to alternative platforms and have become more careful of their digital footprint going forward.

Reliable OSINT

The credibility and reliability of sources has been a consistent challenge for OSINT. With the sheer size of January 6’s digital footprint, however, multiple sources of digital evidence could corroborate and triangulate each other. In the case of one defendant, law enforcement observed her in the New York Times visual investigation “Day of Rage” marching to the Capitol and confronting police at the steps of the building. She was also found in a video taken by another rioter. Surveillance video from the Capitol shows her entering and walking through the building. She later posted a photo from January 6 on Instagram of the area around the Capitol building, while other content from her Instagram and MeWe profiles assisted in further identifying her along with her prior extremist activity. Law enforcement also used geofence data (obtained via search warrant) and flight records to place her at the Capitol riot. Indeed, charging documents show that many of the January 6 defendants were identified by law enforcement using these triangulation methods — largely based on OSINT — to piece together proof that they were involved. The challenge of the reliability of OSINT data was able to be overcome through the large amount of digital evidence available.

Safer prosecutions

ISD’s review of charging documents against January 6 defendants found that only 3% were identified by tips from relatives, friends, co-workers, former romantic partners and other associates without law enforcement’s use of OSINT. Several defendants who were charged at least partly on the basis of OSINT were also initially identified by tips, but their participation in the attack was corroborated by their publicly available digital footprint.

While witnesses play an essential role in the criminal justice system, their participation can result in “retaliation by violence or threats of violence.” In the case of a teenager who reported his father to the FBI for participating in the Capitol riot, for example, the suspect had warned his family that “traitors get shot.” The exceptionally low significance of witnesses in conjunction with the high significance of OSINT in January 6 trials suggests that the large amount of digital evidence available contributed to fewer people having to risk their relationships and wellbeing. Ultimately, this can lead to safer criminal investigations.

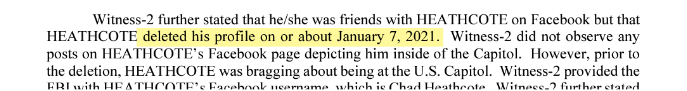

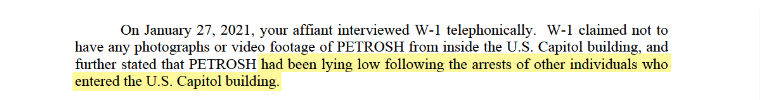

Lying low

Several charging documents show that defendants took down their January 6 posts on social media and deleted their profiles altogether. In one case, the defendant deleted their Facebook profile on or around January 7 (see figure 3 below). Another defendant “had been lying low following the arrests of other individuals” from the attack (see figure 4 below). As rioters began deleting their online profiles, social media platforms also suspended accounts of January 6 participants. This ultimately led far-right communities “to scatter across alternative platforms,” and to an “increasing commitment to operational security from the far-right.”

Figure 3. Statement of facts in US v. Chad Heathcote stating that suspect deleted their Facebook profile immediately after January 6, 2021. Source: US Department of Justice.

Figure 4. Statement of facts in US v. Robert Lee Petrosh stating that suspect was “lying low” after January 6, 2021. Source: US Department of Justice.

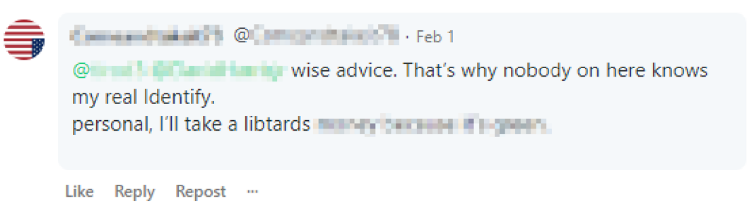

ISD’s online monitoring of extremist spaces in the last two years also supports these assessments. Figure 5 below, for example, shows a far-right user’s post on Gab in February 2022 where they claim that “nobody on here knows my identity.” This Gab profile does not contain the user’s real name or any identifying photos.

Figure 5. Post on Gab from a user who acknowledges that they take steps to hide their identity (February 2022).

Conclusion

The publicly available digital footprint of the January 6, 2021, attack on the US Capitol is rich with online posts planning the event and photos and videos depicting the attack and its perpetrators from virtually all angles. The heavy use of OSINT by journalists, civil society and online sleuths to analyze the attack and the subsequent reliance on this work by Congress and law enforcement represents a milestone for OSINT. While domestic extremists appear to be more aware of their digital footprint and are migrating to alternative platforms with anonymity in mind, the significance of OSINT in law enforcement’s pursuit of Capitol rioters suggests that investigations were far more reliable and safer.

Appendix

Methodology

The Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) reviewed charging documents for 940 individuals charged by the Department of Justice (DOJ) for crimes related to the January 6 Capitol attack. The charging documents are either statements of fact, criminal complaints or indictments, which typically refer to law enforcement’s investigative methods to establish probable cause for criminal charges.

ISD conducted an analysis of all relevant charging documents — totaling nearly 10,000 pages — to determine if they mentioned open-source research (OSINT) as one of the investigative methods used by law enforcement to investigate the defendants.

The remaining defendants where OSINT was not mentioned or where relevant charging documents were unavailable (e.g., plea documents were available but did not refer to investigative methods) were further categorized by the primary investigative method, as determined by ISD.

ISD used the following labels to categorize the 940 defendants’ cases:

- OSINT (826; 87.9%). Defendant was charged at least partly on the basis of OSINT. We refer to “OSINT” as law enforcement conducting open-source research to find social media profiles, photos and videos available online, or other publicly available user-generated content, government records, media, or commercial records. Note that cases labeled as using OSINT did not exclusively rely on this investigative method. Cases often made use of, for example, OSINT, CCTV footage, and tips received by law enforcement. Our primary interest was whether they used OSINT at all.

- Other (17; 1.8%). Defendant was charged due to initial findings from police body-worn cameras, Capitol CCTV footage, and/or information obtained by search warrants served on telecommunications- and internet-service providers (e.g., geofence and account data).

- Tip (28; 3%). Defendant was identified via tips submitted to law enforcement by individuals such as relatives, co-workers, and other rioters.

- Self (6; 0.6%). Defendant voluntarily identified and/or turned themselves in to law enforcement in the days after the attack.

- On-site (16; 1.7%). Defendant was arrested at or near the Capitol on January 6.

- N/A (47; 5%). Charging documents for the defendant were not available or did not mention investigative methods used by law enforcement.

The vast majority of documents were made available online by George Washington University’s Program on Extremism (PoE). When documents were unavailable through PoE’s set, ISD referred to documents provided by the DOJ’s “Capitol Breach Investigation Resource Page.” ISD has referred instances of incorrect names or documents to PoE for correction.