Flash Briefing – Election Fraud Narratives in Response to the Australian 2022 Federal Election Results

24 May 2022

By Elise Thomas

The conspiracy theory and anti-lockdown movement in Australia has strong ties to several of the minor and micro-parties which ran candidates in the 2022 Federal election. In some cases, the parties emerged from these movements; in other cases, existing parties participated in events associated with them (rallies, panel discussions, etc.) and sought to win their votes.

Of these parties, all but two have failed to get any candidates elected: The outcome of the Senate elections in Victoria and Queensland remain unclear at the time of writing, but it is possible that One Nation’s Pauline Hanson and United Australia Party’s Ralph Babet may win their seats.

This almost complete defeat of the self-described “freedom friendly minor parties” could be expected to be met with anger, disappointment and potentially the propagation of election fraud conspiracy theories amongst their supporters. As part of RMIT FactLab’s Mosaic Project, researchers from ISD and CASM Technology set out to analyse their reaction.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Within existing conspiracy theory groups on Telegram and Facebook, allegations of election fraud are currently widespread but mostly non-specific. Two days after the result of the election was announced, there has been no indication of this narrative gaining traction outside those existing groups.

However, it does appear that at least two legal challenges may be mounted based on claims that the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) interfered with the election, either through intentionally providing incorrect advice about how to vote or by interfering with the ballots in some manner. If these challenges are mounted, they are likely to amplify narratives about election fraud.

The following Dispatch provides an initial overview of the most common forms of election integrity conspiracy theories and discourse we have observed in existing conspiracy theory groups on Telegram and Facebook in the immediate aftermath of the election.

Suspicion in search of a narrative

The most common form of election integrity discussion happening in the (roughly) 36 hours following the election appears to be general but unspecific allegations of fraud – for example, many statements such as “It was rigged!” without an underlying narrative as to how it may have been rigged. This appears to be a relatively widespread sentiment, although not a consensus, across conspiracy theory groups on Telegram.

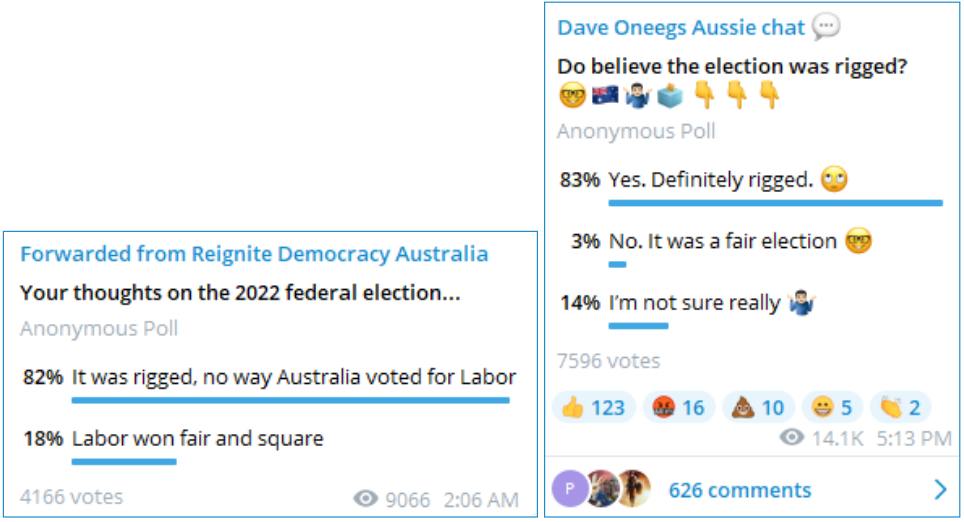

A poll posted by anti-lockdown group Reignite Democracy (the leaders of which both ran failed campaigns as independents for the Victorian Senate), for example, asked its followers whether the election was rigged. 82% of the 4166 respondents felt that it was, with no further information as to how, or by whom. A very similar percentage, 83%, also agreed that the election was “Definitely rigged” in a poll by anti-lockdown influencer Dave Oneeglio.

Image 1: Examples of posts claiming the election was “rigged”.

Image 2: Polls posted by the anti-lockdown group ‘Reignite Democracy’ (left) and anti-lockdown influencer Dave Oneeglio (right).

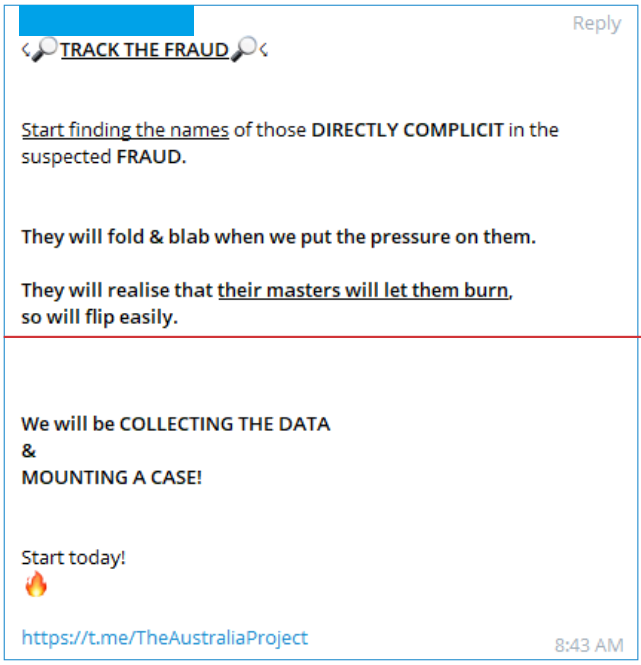

There does appear to be an active search underway to find “evidence” of election rigging around which a narrative can be built. Sovereign Citizen group The Australia Project (TAP) has been asking users in multiple Telegram channels to send in any evidence of election rigging. In particular, they have been asking for the names of individuals who may have participated in election rigging – this is a concern as it creates the potential for harassment of AEC staff, volunteers or others involved in the election process.

In a video on Telegram, a TAP influencer claims that the group are “about to lead the charge on this”. He also suggested that there might need to be a re-count of the ballots and called for his followers to use “guerrilla tactics” to corner politicians and “demand answers” from them. “We the people will cause trouble for you if you’re going to try and steal our country from us,” he said.

Image 3: A post on Telegram showing a potential effort by TAP to harass AEC workers.

Potential legal challenges based on alleged AEC mishandling of votes or provision of incorrect advice

It appears that a small number of candidates are planning to dispute the election result based on allegations of AEC staff tampering with votes or intentionally misleading voters about how to vote. Failed United Australia Party Senate candidate and chief funder Clive Palmer has announced his intentions to mount a legal challenge in one seat. Palmer claims to have video evidence of AEC staff taking ballots home. The AEC says that it has seen no evidence of this.

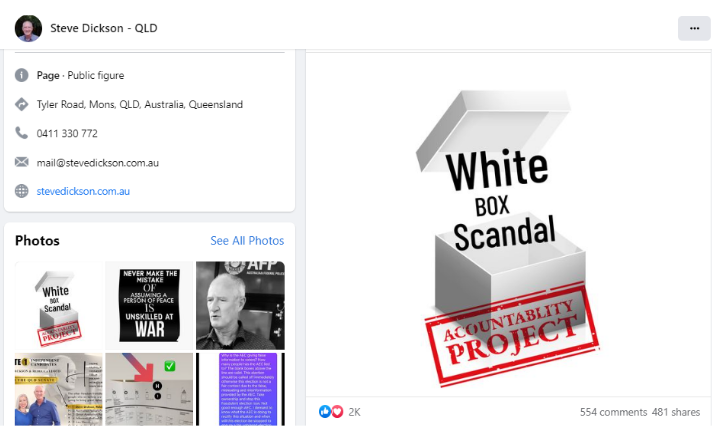

Failed candidates Steve Dickson and Rebecca Lloyd are also leading a push to challenge their election results. Dickson and Lloyd are seeking to build momentum behind this push on social media, with Dickson attempting to brand it as the ‘White Box Scandal.’

This narrative dates back to before the election on 18 May, when Dickson, Lloyd and other candidates published a video featuring recordings of phone calls between members of the public (presumably supporters of the “freedom friendly minor parties”) and AEC workers.

In the calls, AEC workers gave out incorrect advice as to how to fill out the Senate ballot. This has been interpreted as a deliberate attempt to undermine the votes for independents in the Senate, as opposed to genuine mistakes by a swiftly-trained workforce.

Dickson claimed on 23 May to have secured an interview with controversial but high-profile right-wing commentator Alan Jones on this topic later in the week. If this occurs, it is likely to reach a significantly larger audience.

Image 4: Steve Dickson attempting to brand his electoral defeat as the ‘White Box Scandal’ on his Facebook Page.

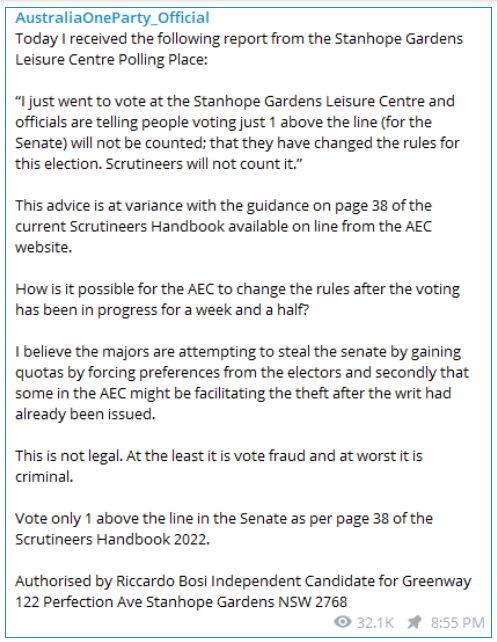

Other cases of incorrect AEC advice interpreted as election fraud

Another example of incorrect AEC advice being interpreted as deliberate rigging is a post by independent candidate Riccardo Bosi, also on 18 May. Bosi posted about an incident where one of his supporters was allegedly given incorrect Senate voting advice and claimed this represented an attempt to “steal the Senate”. “At the least it is vote fraud and at worst it is criminal,” he wrote (Image 5).

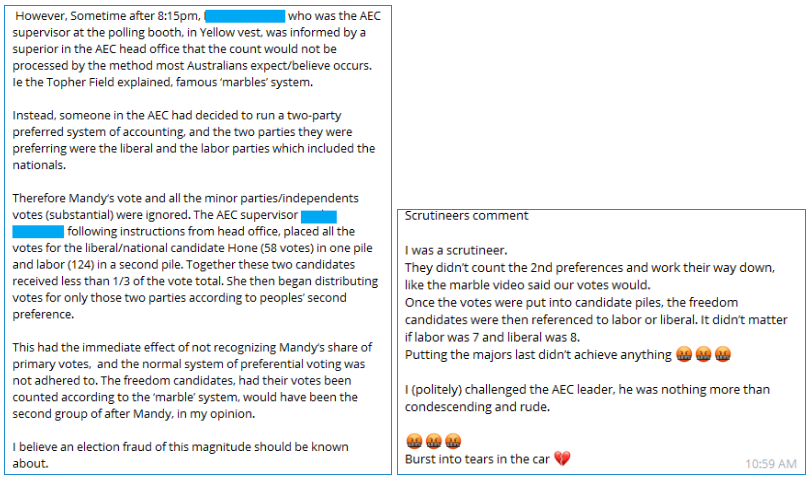

Another example, which appears to be getting some attention following the election result, is the allegation that votes were counted differently to the way in which they were counted in a popular video from an independent candidate which explained preferential voting using marbles (Image 6). This was interpreted as a sign of fraud (as opposed to recognition of the fact that, in reality, the marble video was not an accurate reflection of how lower house votes are counted).

There has been some pushback against this from within the anti-lockdown and conspiracy theory community, however. Some people who scrutineered on the night have sought to explain the vote count process more clearly. High profile anti-lockdown influencer Joel Jammal, for example, published a video explaining the process and stating repeatedly that the vote was not rigged in this specific way. He did however allege other forms of election fraud, such as people voting multiple times, with no evidence.

Image 5: A Telegram post from independent candidate Riccardo Bosi, interpreting incorrect AEC advice as deliberate election rigging.

Image 6: Users on Telegram allege that the votes were counted differently to Topher Field’s ‘marbles’ system.

Continuation of Sovereign Citizen conspiracy narrative that the election is illegitimate

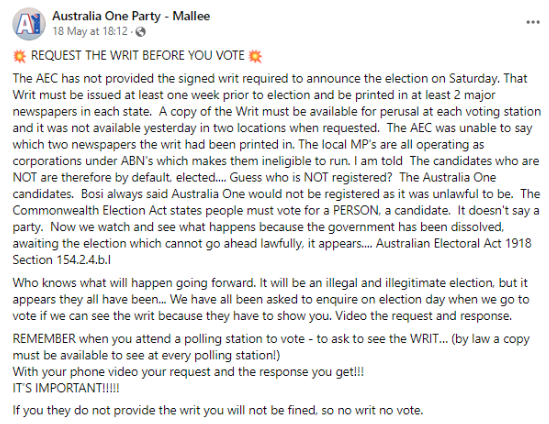

Shortly after the election was called, a Sovereign Citizen-style conspiracy theory claiming that the election itself was invalid begun to circulate, based on the idea that correctly authorised writs for the election have not been made available to the public. In the lead-up to the vote, some independent and minor party candidates encouraged their supporters to demand a copy of the writ at their polling place.

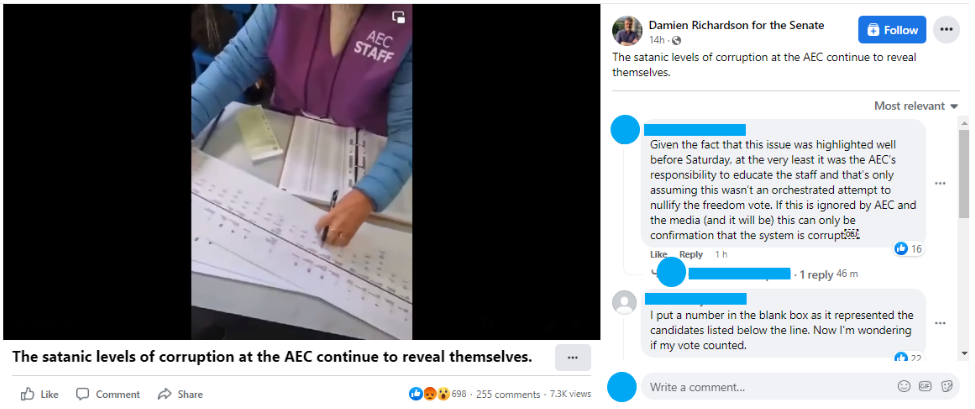

Following the election, a small number of videos showing individuals asking to see the writ in polling places, and the writ not being provided, have been shared around social media groups. This includes a video shared by failed Senate candidate Damien Richardson on Facebook which refers to the supposed “satanic [sic] levels of corruption at the AEC”.

Image 7: Australia One Party encourages their supports to request a copy of the writ at their polling place.

Image 8: Video shared on Facebook by failed Senate candidate Damien Richardson.

Narratives about the World Economic Forum and ‘Great Reset’

A two-part briefing published last week by ISD as part of the Mosaic Project analysed the role which narratives about the World Economic Forum (WEF) and ‘Great Reset’ played during the 2022 election campaign.

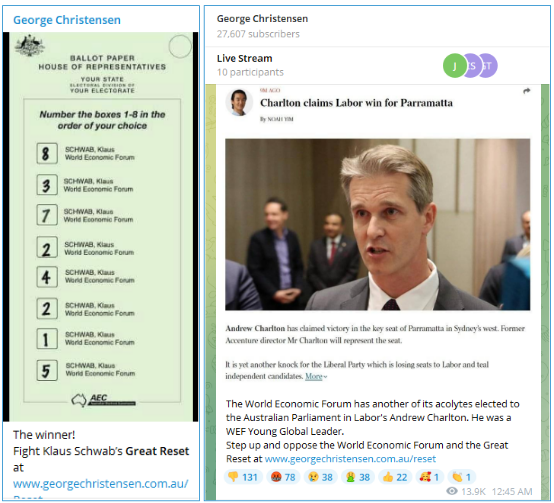

These narratives, alongside related narratives about the World Health Organisation, continue to proliferate in the aftermath of the election. Most notably, former Coalition MP and failed One Nation Senate candidate George Christensen posted on Telegram that the election had been a victory for the WEF and its founder Klaus Schwab.

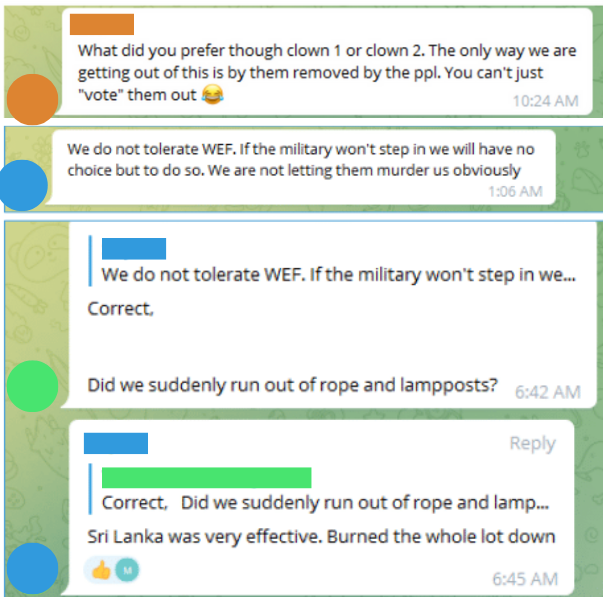

Christensen also alleged that Labor’s successful candidate for the lower house seat of Parramatta, Andrew Charlton, was linked to the WEF. This resulted in a string of comments attacking Charlton, including some with implied threats of violence (Image 11).

Image 10: (Left) Telegram post from failed One Nation Senate candidate George Christensen claiming that the election had been a victory for the WEF and its founder Klaus Schwab; (Right) Telegram post from Christensen claiming Andrew Charlton was linked to the WEF.

Image 11: Comments attacking Andrew Charlton in response to Christensen’s Telegram posts.

Discussion

It is still very early days, and much of the obvious emotional response to the failure of the “freedom friendly minor parties” from their supporters has yet to coalesce into a solid narrative. However, that frustration, disappointment and reflexive suspicion is very likely to be harnessed by influencers and failed political candidates from these communities. According to two Telegram polls from high profile influencers, upwards of 80% of respondents believe the election was rigged. It is notable that there are influencers within the anti-lockdown community who are seeking to push back on claims of rigged vote counting, although they do amplify other claims about illegitimate voting practices.

Overall, the risk of election integrity conspiracy theories taking hold in any widespread sense appears to be low. If legal challenges are mounted against the results on the basis of alleged fraud by the AEC, this could be expected to amplify those narratives (including via mainstream media coverage) but it does not follow that many would be convinced by the claims.

However, it is likely that the AEC’s social media accounts, complaints and fraud reporting lines and potentially some AEC workers may face a level of harassment and spurious claims. This is a serious and concerning development, particularly for individuals who may be intimidated out of participating in supporting the AEC’s work in future elections.

This briefing is supported by the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas in partnership with RMIT FactLab, the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) and CASM Technology.

Elise Thomas is an OSINT Analyst at ISD. She has previously worked for the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, and has written for Foreign Policy, The Daily Beast, Wired and others.