Fake health passes are easily moving across French social media despite platform policies

14th February 2022

Zoé Fourel, Jiore Craig & Iris Boyer

In France, the past two weeks have seen fake COVID-19 health passes (“pass sanitaire”) linked to individuals hospitalised with COVID-19 symptoms. While authorities look to hold those producing falsified health passes responsible, the discussion so far has failed to address how these fake passes are moving into the mainstream social media.

For months, ISD analysts have watched the sale and promotion of fake health passes across both fringe and mainstream social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Telegram and Snapchat.

As omicron cases continue to rise in France and an election campaign looms, ISD’s research illustrates how the free movement and sale of fake health passes online reflects both the failures of social media platform policies and French legislation to prevent bad actors from targeting the French public.

_________________________________________________________________________________

The journey of a fake health pass on social media

Imagine you are spending time on your favourite social media platform. In France, that’s likely to be Facebook, WhatsApp, or if you have more niche interests, a platform like Telegram. You might be frustrated with the pandemic or, like half of the French public, dissatisfied with how the government is handling vaccine mandates or other COVID-19 restrictions. Maybe you decide to join a social media group, where like-minded people share your frustration and express their feelings through posts.

According to ISD’s research,[1] upon joining such a group it is likely you would quickly encounter content advertising fake health passes. From the start of our ethnographic monitoring work in France, analysts have come across numerous access points to fake passes across Facebook, Instagram, and Telegram. On each of these platforms, posts were accompanied by contact information directing users to other spaces including Snapchat and WhatsApp, illustrating how the fake pass business bridges multiple platforms.

Some pushing fake passes have political objectives and seek customers who are looking to protest government mandates. Others sell purely for profit.

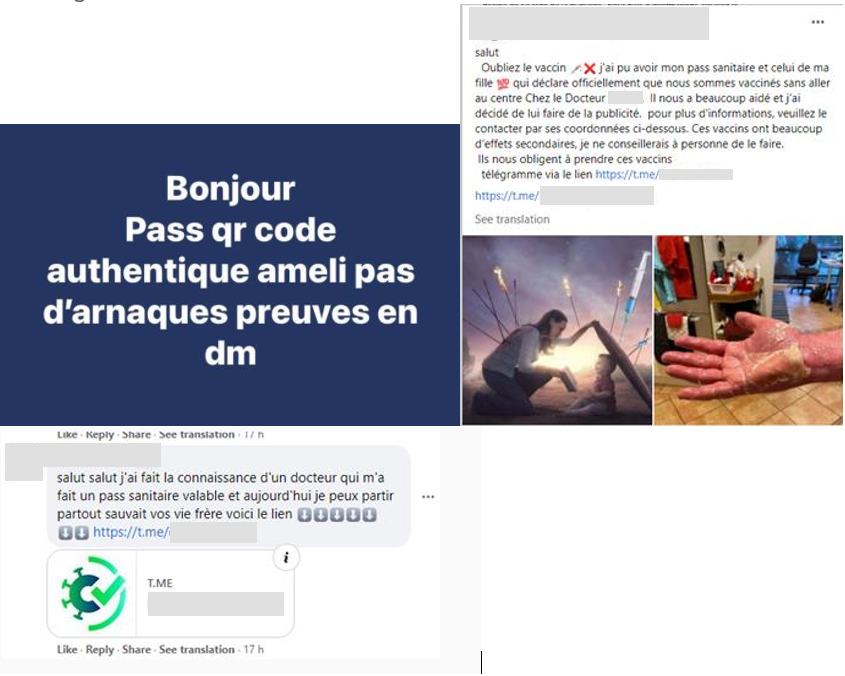

The following illustrates a few examples, from Facebook, Instagram and Telegram, of how a user might find and purchase a fake health pass online.

Facebook and Instagram

As the largest platform in France, the prominence of fake passes on Facebook is of particular concern. Users can find fake passes for sale on Facebook itself as well as being directed to other platforms, including more extreme spaces.

The promotion of fake health passes largely takes place in closed groups organised around COVID-19 or vaccine protest movements, with users advertising fake QR codes for sale through direct messaging, other Facebook accounts, or public channels and private accounts on Telegram. For example, one link directing to Telegram routed to a public channel with 85 subscribers, providing fake health passes and encouraging subscribers to get in touch with a private account on Telegram for the sale.

Figures 1, 2 & 3: Examples of Facebook posts promoting ways to get fake health passes on Facebook and Telegram.

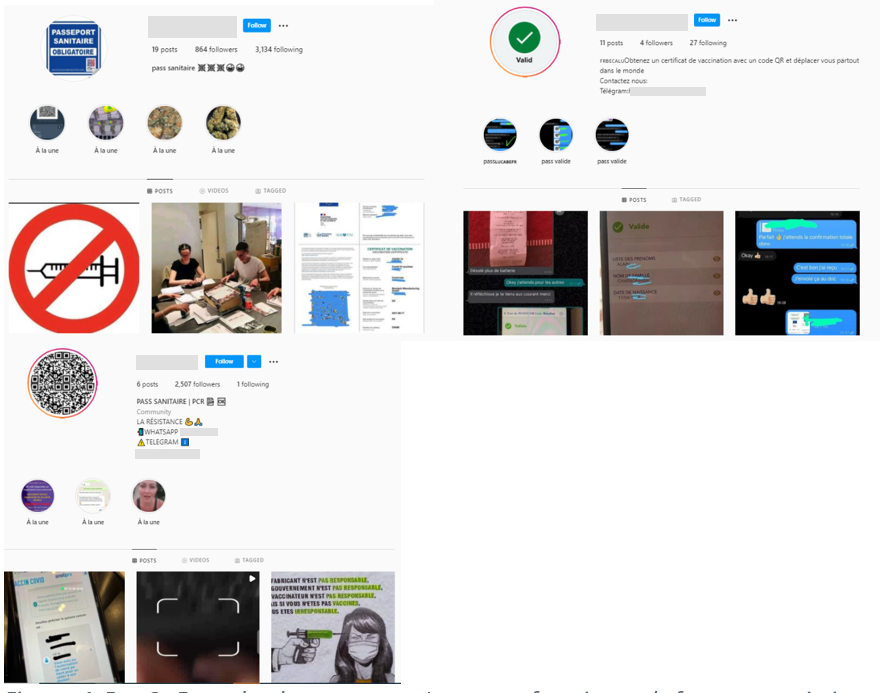

ISD also found several accounts on the Meta-owned Instagram which specifically promoted “pass sanitaire” (health pass) in their account handle, making it easy for even those looking for genuine passes to come across their account. These Instagram accounts all contain contact information to get in touch with fake health pass providers on other platforms (Telegram, Snapchat, WhatsApp, etc.).

Figures 4, 5 & 6 : Examples of accounts on Instagram providing fake health passes.

Facebook and Instagram both have COVID-19 policies aimed at preventing this kind of activity. However, the ease with which analysts found this content raises serious questions about the efficacy and enforcement of these policies.

For example, Facebook’s policies claim to remove content promoting deceitful practice and counterfeit products such as fake or forged documents, and ban the advertising of deceitful practices including the promotion of fake documentation and products enabling the bypassing of security controls. Facebook also claims it is committed to “helping bring people one step closer to getting vaccinated and having access to the most reliable and authoritative information about vaccination and health measures.” Unfortunately, the platform is also providing people with access to illegal passes aimed at circumventing public health measures.

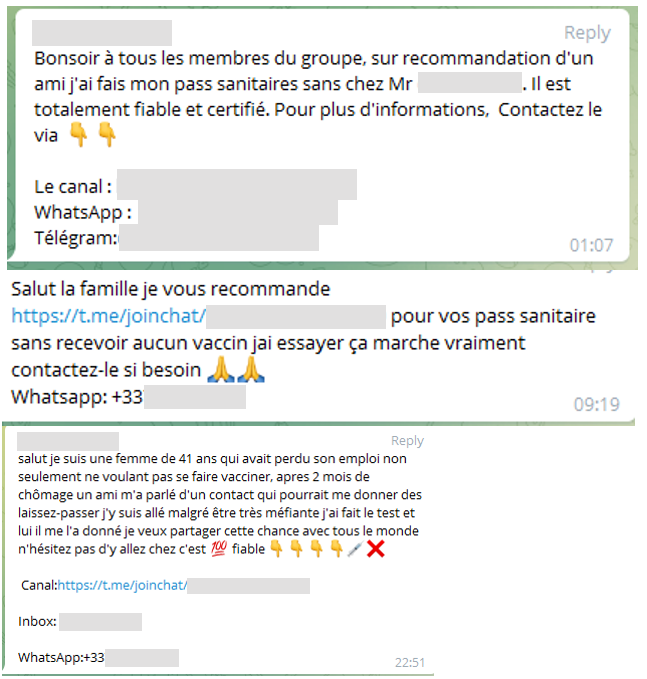

Telegram

Telegram attracts users tired of platforms owned by Meta as well as those with niche interests, including extreme ideologies. ISD found several ways to acquire fake health passes in a channel dedicated to subverting health restriction measures.

This Telegram channel maps out public spaces and businesses across France that allegedly do not require the health pass. It also promotes anti-vaxx content, COVID-19 conspiracy theories, disinformation, and the sale of fake passes. In the comment section of several posts, users can find fake pass providers on Telegram and WhatsApp.

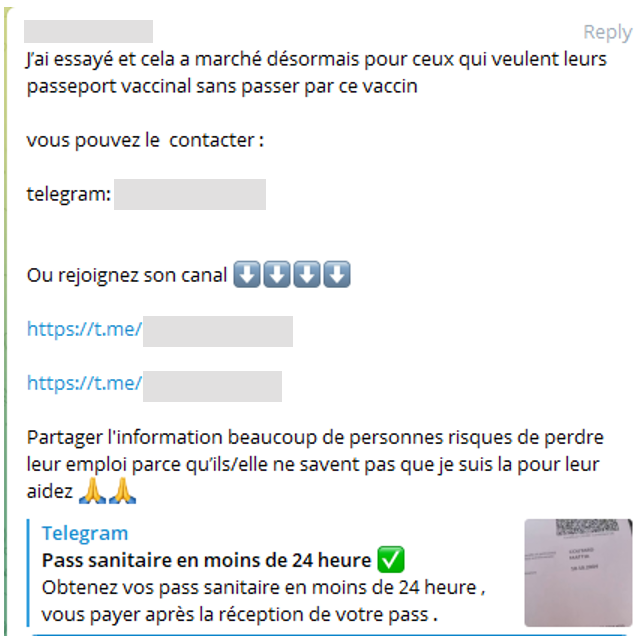

Figures 7, 8, & 9 : Examples of comments found in a Telegram channel dedicated to coordinating anti-health pass action as well as spreading COVID-19 conspiracies and disinformation.

Fake health passes are also being advertised in Telegram channels dedicated to topics other than COVID-19 disinformation and conspiracies or anti-vaxx content. One such example was found in an identitarian youth group under posts which were unrelated to COVID-19, further demonstrating the overlap between right-wing extremism and attempts to subvert public health measures related to COVID-19.

Figure 10: Example of a Telegram comment advertising fake passes, shared under a post unrelated to COVID-19.

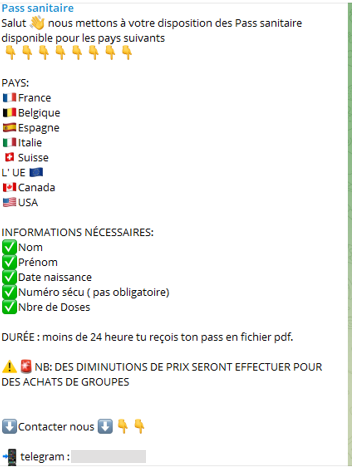

There are clear indications this activity is being monetised. In one of the Telegram channels reviewed, a post indicated discounts are available to those who ordered several fake health passes at once.

Figure 11: Example of a post indicating fake health pass activity is being monetised.

Telegram’s relatively minimal and privacy-oriented terms of service require its users to agree not to scam other users or promote violent action in public channels. The only illegal content they ban on public channels is pornographic content.

Their advertisement policy meanwhile bans “deceptive, misleading, or predatory advertising”; “Deceptive or harmful financial products or services”; and “Medical services, medications” and “Products of questionable legality”. Further, “Ads must not promote content, products, or services related to health and wellness (…) Forgery, including fake IDs, passports, visas, official documents, (…) Stolen or leaked data (…), Counterfeit products, (…) or inauthentic digital goods.”

Consequently, much of the content ISD found appears to contravene Telegram’s advertisement policies if not their broader terms of service.

Transnational sales

The transnational dynamic of the fake pass business has become clearer as more COVID-19 restrictions are implemented across Europe. In one English-language Telegram channel providing updates on the activity of European far-right groups, users identified opportunities to obtain fake EU digital COVID-19 certificates.

Under a post about Yellow Vests moblisation against French health passes, one commenter provided the contact of a private Telegram account selling fake health passes to EU citizens. The only requirement to acquire this fake pass is to have a valid European ID or residency. According to the seller, the pass would be valid across Europe and indicate the holder had received two Pfizer doses.

Figure 12 : Example of comment which offers EU fake health passes.

Policy Failures

The French government appears to be taking the issue of fake health passes seriously. The Ministry of Interior recently reported that around 200,000 cases of fake health passes had been identified and 435 related investigations had been opened. In the context of new legislation which changed the health pass into a vaccination pass (as of 24 January), the French government has made its determination to regulate such abuses clear, defining stricter sentences for those found to be creating, profiting from or using fake passes. Fake vaccination pass holders can be fined up to 45,000€ and face up to 3 years in prison. This sentence can go up to 5 years and a 75,000€ fine for those holding several fake vaccination passes or producing, providing and selling fake passes.

However, social media companies’ accountability for allowing these schemes to proliferate on their platforms has yet to be highlighted in the context of domestic regulatory developments. Neither has it been mentioned in any recent communication from the Audiovisual and Digital Communication Regulatory Authority (ARCOM), the new regulatory agency formerly known as CSA, despite its dual mission to control broadcast and technology platforms.

It is also unclear to what extent the Directorate-General for Media and Cultural Industries (the Ministry of Culture’s department in charge of technology platform regulation) is addressing this issue or working with other government and independent stakeholders like the Ministry of Interior and ARCOM to hold platforms accountable for this. The department has however demonstrated an appetite to collaborate with academics so as to keep track of the latest developments surrounding online abuse and information manipulations as demonstrated in its participation in ARCOM’s Online Hate Observatory.

Similarly, the heated parliamentary debates around the introduction of the vaccination pass do not seem to have specifically tackled or substantially reported on the issue, although surrounding discussions extensively covered the responsibility of other stakeholders including representatives of the French national health agency and ill-intentioned doctors.

Gaps in Media and Academic Reporting

Beyond a handful of articles covering specific cases of social media failures around the advertising of fake passes, the French media has instead focused on investigating offline networks and their illegal tactics. Only anecdotal reports mention the connection between social media activity and the trafficking of fake health passes, and often not through a domestic lens despite the serious consequences this online activity has had.

Moreover, brief desk-based research examining the outputs from French academia and advocacy groups who focus on online information threats or digital regulation did not show any recent or meaningful reporting on this issue either.

Lack of accountability and proactivity amongst platforms

Companies like Meta and Telegram have been quiet on this issue. Their reaction to their platforms facilitating this fraudulent activity is reminiscent of their attitude towards the spread of false information about COVID-19 at the beginning of the pandemic. With regard to Facebook, this response stands in stark contrast to the measures they claim to have adopted over the past two years. Specifically, to moderate and label manipulative content and prioritise health information from authoritative sources through their recommendation systems.

This perception of passivity with respect to users’ attempts to undermine public health measures is not aided by the companies’ terms of service for illegal content, which differ significantly between user-created content and illegal advertising. In the case of Telegram in particular, the company’s rules on advertising are substantially stricter and more detailed.

This suggests that the question of illegal advertising seems to be prioritised by social media policies and moderation efforts, over the equally problematic concern of the organic but large-scale promotion of monetised illegal services and documentation.

The challenging application of French law in practice

Despite France having relatively advanced laws for dealing with disinformation, this coordinated sale of fake health passes makes clear there is more work to do.

The 2018 law on the manipulation of information pushed platforms to be more transparent and gave more power to ARCOM to monitor and report on their compliance and efforts to combat disinformation.

In practicality however, real-time identification and mitigation of hybrid threats which sit at the crossroads of information manipulation and illegal trafficking is a challenge which the French government is currently wrestling with, mainly through the law enforcement work of its Ministry of Interior and new legislation.

The French government’s eagerness to foster a collective understanding and solution-oriented multi-stakeholder taskforce to observe and report on such emerging threats has recently been demonstrated with the creation of different bodies like the Viginum Agency and the Bronner Commission, whose recommendations are soon to be published.

But the apparent lack of proactivity from both platforms and government to meaningfully address the question of social media companies’ responsibility in enabling such a harmful and large-scale phenomenon is worrisome, especially given the context of the upcoming application of the European Digital Services Act (DSA) where many are calling for the French government’s leadership in this process.

Given the transnational nature of this activity, the DSA is the type of policy urgently needed to address these harms across Europe. It provides a series of requirements that online intermediaries must meet in order to benefit from the limited liability regime previously defined in the 2000 European e-Commerce Directive. The general idea is that online intermediaries will need to step up their response to the harmful impact of their services if they do not want to be held accountable for user-generated content on their platforms.

One key measure requires the cooperation between platforms and national authorities in the process of removing illegal content and activity. Special attention needs to be given to understanding and hampering sophisticated cross-platforms communication strategies. To this end, tech companies should be pushed to establish enhanced cross-services cooperation, also informed by academic and media investigations, in order to map and staunch these networks’ platform migration tactics from promotion to monetisation.

In the absence of a responsible and proactive attitude from social media platforms, civil society and the media must show leadership in exposing and addressing the mainstreaming of abuse of online services for information manipulation and the harmful promotion of related illegal commercial activities. In turn, the government must also step up its efforts to hold platforms to account, enforcing both existing law and moving more quickly on advancing the DSA and similar regulation.

[1] ISD conducts ongoing ethnographic monitoring of online spaces including Facebook, Instagram, and Telegram. This French language analysis was conducted between October 2021 and January 2022.

This Dispatch is also available in French.