How Eric Zemmour’s election campaign used petitions to distort online support ahead of the French elections

27 September 2022

This Dispatch provides a summary of findings from our report “Amplifying Far-Right Voices: A Case Study on Inauthentic Tactics Used by the Eric Zemmour Campaign“. This report is also available in French.

________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

Early 2022 French election coverage was dominated by discussions of the possible candidacy of controversial presidential hopeful Eric Zemmour. The then-journalist joined the race in November 2021 and his central talking points continued to be featured front and centre in French media and French-language social media. Zemmour’s campaign focused on far-right issues, with key concepts of the French Identitarian movement such as the Great Replacement or ‘Reimmigration’ at the very core of his ticket. Nevertheless, a clear discrepancy between the scale of media attention given to Zemmour and his actual support among the French public at the ballot box can be seen throughout the presidential and legislative races. Zemmour scored a mere 7% in the first round of the presidential election, and his party “Reconquête” failed to gain any seats in the French National Assembly during the legislative elections.

Previous investigations have highlighted the use of suspicious online techniques, including astroturfing by the Zemmour campaign team[1]. During a project looking at disinformation in the French 2022 election cycle, ISD identified a specific operation deployed by Zemmour’s campaign team[2] mobilising inauthentic behaviour across Twitter and Facebook. This operation consisted of the inauthentic amplification of 12 petitions[3], which were set-up by the support organisation Les Amis d’Eric Zemmour (or Friends of Eric Zemmour). Only two petitions (both created in 2021) openly mention their affiliation with this organisation. The first petition was created over a year before the elections, on 26 January 2021, and the last petition was set up on 5 June 2022, days before the first round of the legislative elections. All 12 petitions were shared inauthentically on Twitter with the Zemmour campaign team found to be at the heart of this strategy. Additionally, ISD found signs of coordinated inauthentic behaviour (CIB) in the sharing pattern of these petitions on Facebook. This occurred despite the fact that both platforms have policies in place prohibiting such behaviour.

This Dispatch summarises an in-depth investigation led by ISD looking at the various strategies used by the Zemmour campaign team to amplify the reach of these petitions on social media ahead of and during the French elections, and the extent to which this activity may have violated Twitter and Facebook policies.

The full investigation is available in French and English.

Methodology

ISD originally identified a total of 11 petitions, using a domain database tool to identify the actors who had registered the domain of each of these petitions. This process enabled ISD to identify that the organisation Les Amis d’Eric Zemmour was behind the domain registration of every petition. On 5 June, a new petition was set up. Observations regarding this petition are integrated into this report, but are not present in all sections of the analysis.

ISD collected all Twitter and Facebook posts containing links to at least one of the 11 original petitions between 26 January 2021 (the date of creation for the first petition) to 26 April 2022. The collection resulted in 108,456 tweets from 19,876 unique accounts on Twitter and 1,204 posts from 385 unique public groups or pages on Facebook. The Twitter dataset was filtered to include only original tweets (excluding retweets), which resulted in a dataset of 30,650 original tweets from 7,840 unique accounts.

ISD used Beam, an information threat detection capability developed by ISD and CASM Technology, to conduct further quantitative analysis, in order to identify potential signs of inauthentic behaviour across both Facebook and Twitter. ISD classified accounts which shared at least one petition by date of creation. To identify potential coordination, ISD analysed instances of cross-posting. For this report, cross-posting is defined as when a post containing a link (in this case, a petition) is shared within a short time (within one minute) of at least one other post containing the same link. This may also indicate coordinated activity. Finally, network analysis was conducted to understand the relationships between the different accounts sharing the petitions.

Inching closer to the vote: Zemmour campaign deploys inauthentic behaviour tactics on Twitter and Facebook

On Twitter, ISD identified signs of inauthentic behaviour in the sharing pattern of all 12 petitions. 20,205 of the 30,650 original tweets that shared at least one of the petitions were identified as potential cross-posts, a substantial proportion. Also, 32% of original tweets shared one of the petitions within 15 seconds of another tweet containing the same link (see Table 1 below). These could be signs of possible inauthentic behaviour.

Table 1: This graph shows the time gap between original posts (excluding retweets) with the same link.

To further establish potential signs of inauthentic behaviour, ISD manually reviewed the datasets of original tweets of all 12 petitions. Very similar sharing patterns were observed for all 12 petitions, which could be another strong sign suggesting inauthentic behaviour.

This strategy was prevalent in March and April 2022, close to the presidential elections that were held on 10 and 24 April – the second date was because no clear majority was decided in the first round on the 10th. ISD observed an increase in the creation of petitions closer to the date of the vote (see Figure 1), with five petitions created in March or April 2022. Additionally, the three petitions created closest to the presidential elections were found to be the most shared (in terms of the number of original posts that shared them) and demonstrated the highest levels of cross-posting. All petitions created in March and April 2022 were designed in the same format, and both their tone and language are very similar, another indication of possible systematisation of the strategy.

Figure 1: A graph showing the volume over time for each petition.

During the election period, ISD saw the Zemmour campaign team strategically share certain petitions to best fit key moments of the presidential campaign. For instance, one petition targeting Macron on the McKinsey affair was re-purposed at strategic times by the Zemmour campaign team.

ISD’s analysis indicates this re-purposing was inauthentic. This petition was created 1 April at 14:19, and the first account to share it on Twitter was Samuel Lafont, head of digital strategy for the Zemmour campaign, at 18:28:33. The exact same text used in Lafont’s first post was then shared 100 times in other original posts by 100 different accounts between 18:28 and 19:05. Throughout April, this petition was shared again: 3,190 out of 5,363 original posts containing this petition used the exact same text as the first tweet from Lafont (see Table 2).

| Date | Number of tweets which use the same text as Samuel Lafont’s tweet (only includes original posts) |

| 01/04 | 838 |

| 02/04 | 1,275 |

| 03/04 | 404 |

| 04/04 | 113 |

| 05/04 | 45 |

| 06/04 | 125 |

| 18/04 | 159 |

| 19/04 | 54 |

| 20/04 | 78 |

| 21/04 | 14 |

| 22/04 | 8 |

| 23/04 | 4 |

| 24/04 | 5 |

Table 2: A table detailing the number of tweets in April 2022 that shared the “Scandale Macron–McKinsey” petition using Samuel Lafont’s text.

The above example was in the lead up to the debate between the two rounds of the presidential elections in April. On 20 April (the debate), Lafont’s account shared this petition 24 times in under five minutes. In this case, Lafont shared the petition in reply to accounts affiliated with sovereigntist figure Florian Philippot, as well as La France Insoumise (LFI) candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon. He also tagged both Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon in several comments, which could suggest Zemmour’s campaign was attempting to rally all sympathisers on both sides of the political spectrum ahead of the debate.

Figures 2, 3, 4: First tweet sharing the petition “Scandale Macron-Mckinsey” by Samuel Lafont at 18:28:33, with examples of tweets sharing the exact same text seconds later.

For all petitions, accounts of the Zemmour campaign were at the very heart of this strategy. Even though only two petitions openly mention their affiliation to Les Amis d’Eric Zemmour, over half of the petitions were first shared on Twitter by an account belonging to the Zemmour campaign team or a member of Zemmour’s party, Reconquête. In half of all cases, this was Lafont. Also, very few accounts were responsible for the majority of original tweets containing at least one petition. Just 0.57% of accounts posted 50% of the original tweets, and four accounts were responsible for sharing over 21% of the original tweets. Lafont was the most active account sharing these petitions (his account was linked to 10% of the original tweets in the sample).

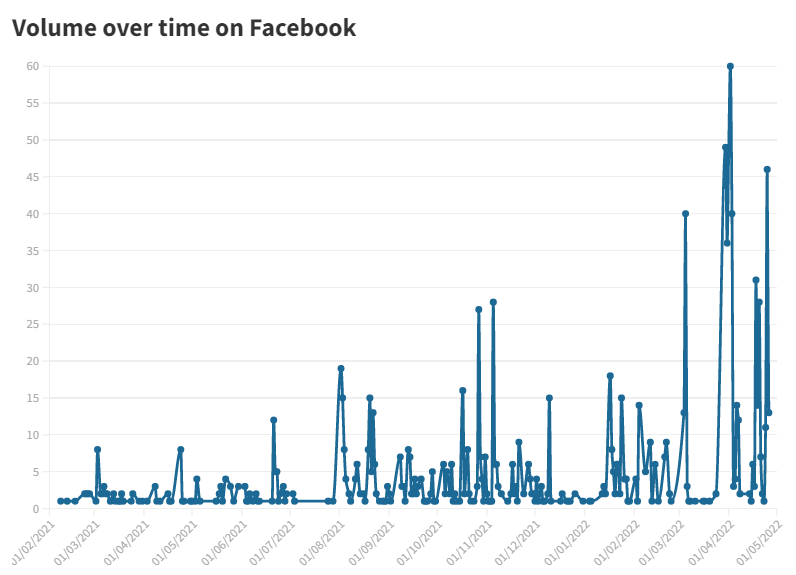

Figure 5: This graph shows volume over time of the sample posts including a petition on Facebook.

ISD found that this petition-sharing strategy was deployed across Facebook as well, with 1,204 posts identified sharing at least one of the 11 petitions. At first, the scale of this phenomenon on Facebook appears to be quite limited when compared to Twitter; however, this number should be read cautiously due to Facebook’s data access limitations[4].

For the 11 petitions, 334 out of 1,127 sampled original posts (about 30%) that contained a petition were cross-posted, which could be an indicator of potential inauthentic behaviour. Similarities in the sharing pattern of petitions were observed between Twitter and Facebook, with an increase in mobilisation closer to the date of the presidential election. In one example, ISD found strong signs of cross-platform CIB operation conducted by the Zemmour campaign team less than two weeks before the first round of the presidential election.

Digital policy implications

Many of the behaviours identified in this investigation violate Twitter and Facebook’s policies. Twitter has several policies regulating coordinated activity including its Platform manipulation and spam policy and its Coordinated harmful activity policy. Among other behaviours which fall under the definition of platform manipulation, Twitter prohibits “inauthentic engagements that attempt to make accounts or content appear more popular or active than they are; coordinated activity that attempts to artificially influence conversations through the use of multiple accounts, fake accounts, automation and/or scripting”. Specifically, Twitter prohibits the use of “technical coordination” on its platform which “‘refers to the use of specific, detectable techniques of platform manipulation to engage in the artificial inflation or propagation of a message or narrative on Twitter.” Nonetheless, ISD found the Zemmour campaign team has coordinated with accounts of the Zemmour ecosystem[5], amplifying the reach of petitions set up by Les Amis d’Eric Zemmour in a potentially automated way. In multiple instances, the Zemmour campaign team has also taken part in inauthentic engagement by repeatedly sharing petitions in the replies of multiple accounts in order to artificially give greater visibility to these petitions. ISD believes the behaviour outlined above matches the definition of technical coordination.

According to Meta, inauthentic behaviour, which is prohibited on its platform, should be understood as “the use of Facebook or Instagram assets, to ‘mislead’ users” about “the identity, purpose, or origin of the entity that they represent”, “the popularity of Facebook or Instagram content or assets”, “the purpose of an audience or community”, “the source or origin of content”, or “to evade enforcement under our Community Standards”. Coordinated Inauthentic behaviour, which also goes against Meta’s community standards, is defined “as assets [that work in] concert to engage in inauthentic behaviour.”

Despite data access restrictions, this investigation brings forward signs of inauthentic behaviour and CIB breaching Facebook’s community standards.

ISD has found signs of inauthentic behaviour with actors amplifying the exact same content across multiple groups in a short period, with the same actors involved in deploying this strategy for multiple petitions. ISD has also found strong signs of CIB led by the Zemmour campaign team in the promotion of these petitions. This is particularly concerning as signs of potential CIB were found less than two weeks before the first round of the 2022 French presidential election and could distort voters’ perception of support for Eric Zemmour and potentially influence their choice at the ballot box.

Conclusion

Despite data access limitations, ISD has uncovered multiple inauthentic behaviour efforts orchestrated by the campaign team behind far-right candidate Eric Zemmour during the 2022 French elections cycle on both Twitter and Facebook.

This case study is another example of distortions within the online ecosystem which threaten to undermine electoral integrity. It is problematic to see inauthentic behaviours continuing to be either un-noticed or tolerated by major social media platforms[i], especially during the presidential elections, a moment of high scrutiny for France’s political life. This is particularly true when platforms have made a point of developing, implementing and trumpeting the successes of policies against inauthentic behaviour and coordinated inauthentic behaviour.

This investigation highlights the lack of enforcement of rules and community standards by Twitter and Facebook. These were clear violations of both Twitter and Facebook’s policy terms and there is no sign of measures taken against accounts that were instrumental in the deployment of inauthentic behaviour or CIB.

[1] ISD’s definition of astroturfing is the following: astroturfing is the practice of masking the sponsors of a message or organisation (e.g. political, advertising, religious or public relations) to make it appear as though it originates from and is supported by grassroots participants.)

[2] By Zemmour campaign team, ISD means individuals who hold a position in Eric Zemmour’s campaign team for the presidential and/or legislative elections. In the context of this report, this would particularly refer to the team that oversees social media activities for the campaign.

[3] All petitions were set-up as websites, requesting signatures for a specific cause/ or support for the Zemmour candidacy/campaign.

[4] ISD proceeds to the extraction of Facebook data through the Crowd Tangle API. Researchers can only extract posts shared by pages and in public groups.

[5]This includes accounts of the Zemmour campaign team members, accounts which identify as Reconquete/ Generation Z members as well as Reconquete and Generation Z accounts (national and local factions).

[i] Colliver, op. cit.