Climate Change Reporting in Hungary: The Evolving Nature of Messaging among Government-Affiliated Media and Pundits

29th June 2021

By Kata Balint

For the past six months, ISD analysts have monitored online discussion about climate change across the Visegrad 4 (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia).

In Hungary, analysts looked specifically at the coverage of climate change issues by media outlets directly or indirectly affiliated with Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz government on Facebook.

________________________________________________________________________

While the vast majority of the Hungarian population is concerned about the effects of climate change and believes that governments’ should take more responsibility in responding to these effects, according to the Climate Change Performance Index there is an overarching “lack of ambition” in Hungary’s national and international climate policy.

To determine how the issue of climate change is portrayed online in Hungary, ISD analysts examined the climate-related content produced by government-affiliated national and local online media outlets, as well as content from well-known and influential pundits connected to these outlets, between 1 January 2019 to 31 January 2021.

Government-affiliated media is critical in shaping public opinion in Hungary. Over the past decade, the media industry in Hungary has seen significant changes, with government-affiliated entities increasingly taking over formerly independent media outlets. Such outlets tend to push narratives that align with the governments’ position on matters, exerting little to no critical examination of the matters at hand.

Methodology

Analysts collected data from 54 Facebook pages of Hungarian national and local media outlets, as well as prominent media pundits, over a two-year period spanning 1 January 2019 to 31 January 2021. The dataset was then filtered using a set of climate-related keywords to exclude non-climate related posts. Of the 587,092 posts collected overall, 4,227 (0.7%) were found to be relevant to climate issues. To analyse trends in climate-related discussion, content was manually coded and classified into 16 narratives.

Key Narratives

Analysts determined 16 core narratives within the dataset. So as to analyse the main trends in discussion, these narratives were grouped into four clusters.

The ‘negative narrative’ cluster

This cluster consisted of six distinct narrative strands that were categorised as hindering the climate discussion.

1- The Anti-Greta narrative was used to describe posts that question or personally attack youth climate activist Greta Thunberg.

2- The Anti-Climate Movement narrative described posts that portray the climate movement as a whole in a negative light, including both new and established ‘green’ entities.

3- The Anti-Opposition narrative referred to posts that criticise the green positions or initiatives of an opposition party, politician or individual.

4- The Anti-EU narrative described posts that discuss the stances of, or measures taken by, the European Union, Member States and/or leaders related to climate change, often with a negative sentiment.

5- The Culture War narrative described posts that connect climate change and the climate movement to other contentious actors and wedge issues. This included meat consumption; migration; the LGBTQ+ community; Black Lives Matter; women’s rights and ‘family values’; George Soros; and the independent press.

6- Posts that openly question the science of anthropogenic climate change and its impacts were categorised within the Sceptic narrative.

The ‘governmental’ cluster

Narratives within this cluster include the key government messages related to the topic of climate change. Analysts identified three main narratives within this group.

1- The We Are the Champions narrative described posts that present Hungary as a champion of climate action, as well as framing national and local climate initiatives by the government (and Fidesz politicians) in a positive manner.

2- The Green Conservative Ideology narrative referenced posts reflecting the idea that environmental protection is an inherently right-wing, conservative and Christian value.

3- Posts categorised under the Pollutants to Pay narrative emphasised the responsibility of other EU Member States, countries and multinational corporations in the fight against climate change.

The ‘positive narrative’ cluster

These narratives centred around awareness-raising messages that could be construed as advancing the climate discussion.

1- The Consequences narrative included posts that relate to the impacts of climate change and raise awareness about the issue, as well as the role human activity has on the environment.

2- The Positive Initiatives narrative described posts that present positive initiatives carried out by various entities to mitigate climate change, both in Hungary and abroad. This also includes the actions of large corporations, which in many cases could be classified as greenwashing.

3- Posts that discuss potential routes to mitigate climate change and its impacts, often emphasising individual responsibility, were grouped into the What to Do? narrative.

The ‘energy’ cluster

Narratives in this cluster were related to energy production.

1- Posts labelled as Pro-Nuclear were in support of nuclear energy, including its promotion as a clean energy source and ‘green’ solution.

2- Posts that advocate for the use of solar energy were grouped into the Pro-Solar narrative.

3- The Anti-Renewables narrative described posts that argue against the use of renewable energy sources.

4- Posts emphasising the negative aspects of wind energy were categorised as Anti-Wind.

Key Findings

Volume of posts per narrative strand

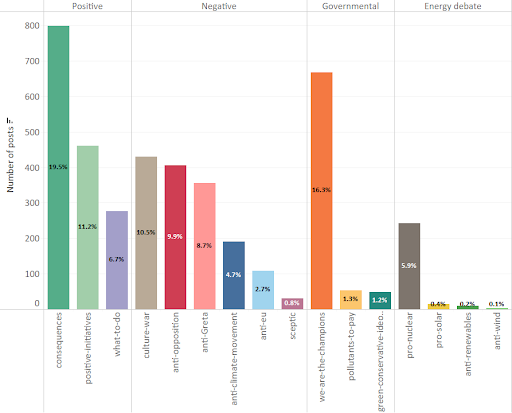

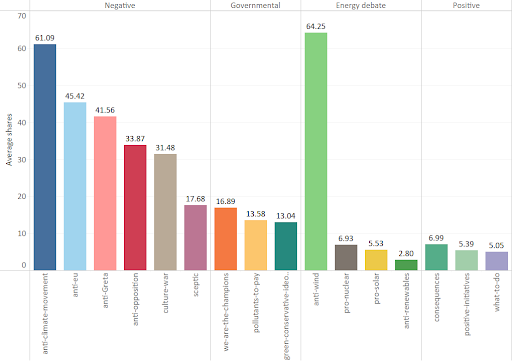

➜Posts within the ‘positive narrative’ cluster (i.e. raising awareness about the consequences of climate change and potential mitigations) were as frequent as those with the ‘negative narrative’ cluster (i.e. attacking the climate movement and green initiatives, or broader climate scepticism). However, as illustrated in Fig. 2, negative content was shared considerably more than positive content, with an average count of 39 vs. 6 shares per post respectively.

➜The most common narrative highlighted the consequences of climate change (19.5% of all posts), followed by the ‘We Are the Champions’ narrative (16.3% of all posts). The latter presented national and local climate initiatives by the government and Fidesz politicians in a positive manner.

➜Only 0.8% of all content could be characterised as questioning the science behind climate change – in other words, hard-line climate change denial was barely present in government-affiliated media.

➜ Narratives targeting European actors and Greta Thunberg were widely shared, with above 40 shares on average per post. Posts opposing renewable energy were the least shared in our sample.

Fig 1. Volume and overall share of posts per narrative strand.

Fig. 2. Average shares per narrative strand.

Note: while posts that criticise wind energy appear most shared, further investigation revealed that out of only four posts in this group, one went viral. For this reason, drawing conclusions from such a small sample can be problematic.

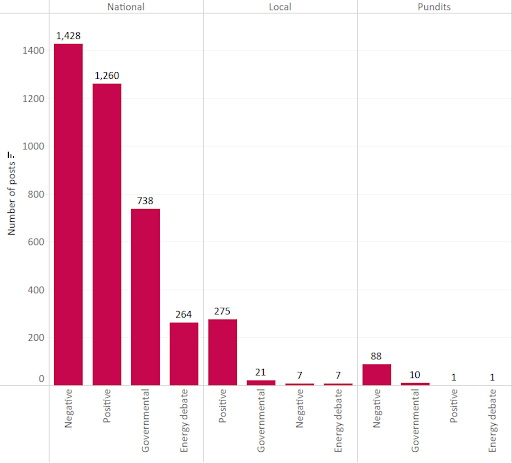

Volume of posts per actor groups

➜National media outlets produced the most content across all narrative groups, with a slightly larger proportion of negative content than positive content. Local media outlets published significantly fewer posts related to climate change and the vast majority of those contained a positive narrative. This suggests that government messaging focused on impeding the climate debate is focused at the national level and that the activity of local outlets does not seem to warrant concern with regard to their reporting on climate change.

➜The opposite can be said about pundits, whose posts were overwhelmingly negative. They produced notably less content than national and local media, yet continued to achieve greater traction and exposure on social media than them: this was demonstrated through the fact that of the top 10 actors whose content produced the most shares, half were pundits.

Fig 3. Narrative volume per actor group (national media; local media; pundits).

The ‘Negative narrative’ cluster

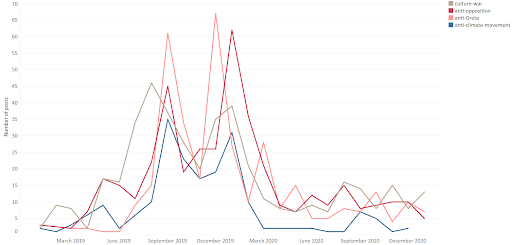

➜Following the European Parliamentary elections in May 2019, analysts observed a sharp increase in climate-related posts from government-affiliated media outlets (Fig. 4). This upward trend appeared to correlate with certain local and global climate-related events, including: the emergence of green activist organisations such as Fridays for Future and Extinction Rebellion (both in Hungary and across the globe); Green parties faring well in the European Parliamentary elections; and opposition candidates campaigning with green issues during municipal elections in Hungary. With the arrival of COVID-19 in the country and across Europe from March 2020 onwards, the volume of climate-related posts declined across ‘negative narrative’ groups.

➜Negative narratives gained prominence in August 2019, spiking in September just before local elections in Hungary. These narratives declined yet still dominated until February 2020, where governmental narratives seem to have taken over for a brief period (which aligned with Prime Minister Orbán announcing a climate action plan for Hungary).

➜Posts criticising Greta Thunberg were more frequent in September 2019 (before local elections) than those attacking the political opposition – this signifies a potential effort to discredit green issues during the campaign. It also demonstrates how divisive certain figures are within the broader ‘culture war’ of climate policy.

➜Posts that connect the issue of climate change to wedge issues reached their peak in August 2019. This may indicate how local election campaigns brought about the politicisation of green issues.

Fig 4. Volume of the ‘Negative narrative’ cluster over time.

Note: The Sceptic and Anti-EU narratives were excluded from this graph due to low post volume.

Summary

This research illustrates that over the course of the past two years, there has been a mixed representation of climate change in the reporting from government-affiliated media in Hungary. While the Fidesz government has tried to position itself as a “green” government, actual nuanced discussion about climate-related policies (e.g. energy policy) was mostly absent in the data. Moreover, despite the governments’ endeavour to portray themself as a champion of climate protection, the groups and individuals who were most strongly vilified by government-affiliated media outlets were those who advocate for stronger environmental policies (such as Greta Thunberg and Fridays for Future).

Of particular note was the fact that content aiming to derail the climate debate was nearly always tied to controversial public figures or wedge issues, signifying that in Hungary, as elsewhere, the topic of climate change is fast becoming a ‘culture war’ inserted into pre-existing strategic narratives to advance other government messaging and agendas.

Kata Balint is an Analyst on ISD’s Digital Analysis Unit. She primarily works on the analysis of the climate change debate in Hungary, using digital analysis tools and open source intelligence methods.